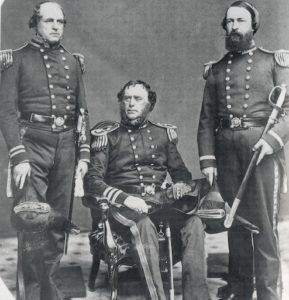

On July 8, 1853, the U.S. Navy’s East India Squadron sailed into Tokyo Bay, marking a pivotal moment in global history. The mission, led by Commodore Matthew Perry, sought to open Japan to Western trade after more than two centuries of isolation. At the helm of Perry’s flagship—the USS Mississippi—stood Captain Sydney Smith Lee, a seasoned naval officer, a Virginia native, and the older brother of Robert E. Lee.

As Perry’s flag captain, Lee helped shape one of the most consequential U.S. diplomatic efforts of the 19th century. The 1854 Convention of Kanagawa followed, establishing formal relations between the United States and Japan.

In 1860, Lee again played a role in U.S.–Japan diplomacy when he was selected to escort Japan’s first official diplomatic mission to the United States. Just seven years after forcing open Japan’s ports, he now welcomed Japanese envoys to American cities in a gesture of formal friendship—a striking full-circle moment in naval history.

But like many Virginians, Lee faced an agonizing choice the following year. In 1861, he resigned his U.S. Navy commission and joined the Confederate Navy. He first commanded the Gosport Navy Yard, then oversaw Confederate naval defenses at Drewry’s Bluff, a key position defending Richmond. He ultimately became the commandant of the Confederate Naval Academy, shaping the next generation of Southern naval officers.

After the war, Lee returned to Virginia and spent his final years quietly. He was buried in Alexandria’s Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery—a peaceful resting place for a man whose career spanned the Pacific and the Potomac, diplomacy and civil war, honor and complexity.