Introduction

The 18th century burials in Alexandria offer a vivid window into the city’s complex history, shaped by the Anglican Church’s dominance, significant strides toward religious freedom, and the city’s evolution from a small settlement to a major port city. This narrative explores how these elements influenced burial practices, early churches’ development, and Alexandria’s evolving social dynamics.

Historical and Religious Context

The Glorious Revolution and the Toleration Act

After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the 1689 Toleration Act in England granted limited religious freedoms to specific Protestant denominations, including Presbyterians, Baptists, and Quakers, known as qualifying dissenters, but excluded Catholics and non-Trinitarians. In Virginia, these groups, despite being officially tolerated, faced strict regulations such as the requirement to keep Meeting House doors and windows closed during services to prevent the spread of what was considered blasphemy. Despite efforts in 1772, a more inclusive tolerance law was stalled until the later period of revolutionary change.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

During the American Revolutionary period, the drafting of the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776, led by George Mason and significantly influenced by James Madison, marked a pivotal shift towards religious freedom. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786 established the separation of church and state, a principle later enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Development of Alexandria’s Religious Communities

Early Challenges and Adaptations

Founded in 1749, Alexandria was part of Truro Parish, which covered areas now known as Arlington, Fairfax, and Loudoun Counties. Initially, worship was limited to Occoquan’s Sanctuary, the Chapel at Goose Creek, and William Gunnell’s Farmhouse, with Falls Church having been established earlier in 1734. At its founding, Alexandria lacked a central church or designated burial grounds, which posed challenges due to the distance to existing churches. This led residents to use garden plots within their properties as makeshift burial sites, demonstrating the adaptability and resourcefulness of the early settlers in managing their religious and burial needs.

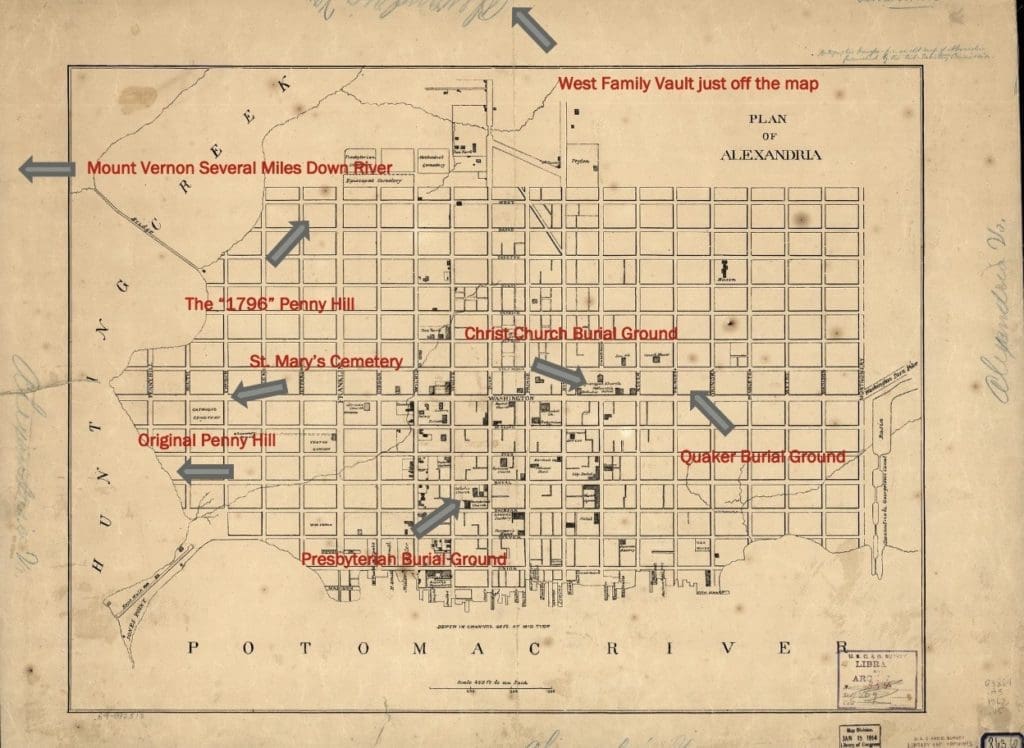

The Establishment of Christ Church Episcopal

By 1762, as Alexandria’s population grew to over 1,200 inhabitants, the need for organized religious and burial spaces became more pressing. Truro Parish had split in 1748, forming Cameron Parish, and another division in 1764 created Fairfax Parish, covering modern-day areas like Alexandria and Arlington County. Within this new parish, the main church was Falls Church, complemented by the Episcopal Chapel of Ease near Alexandria. Christ Church Episcopal, initially constructed in 1773 on the outskirts of town and known as “the church in the woods,” included an associated burial ground from the start, following the common practice of the time. This site became a key burial ground for the community, serving the area until 1809. [Learn more about Christ Church Burial Ground].

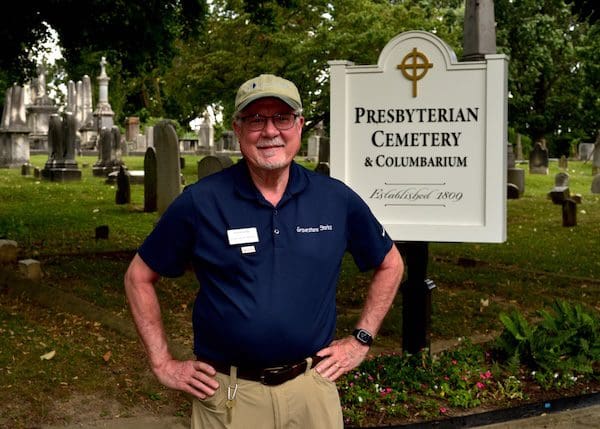

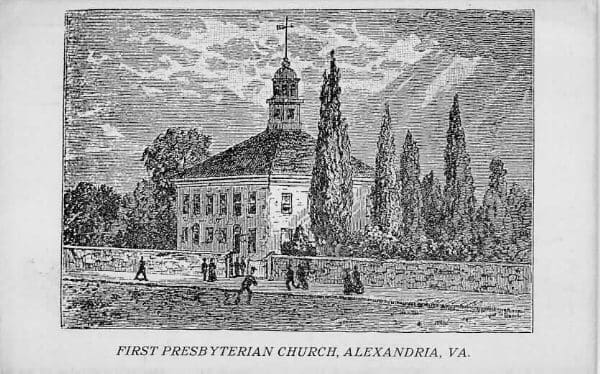

The Presbyterian Meeting House and Burial Ground

In the mid-1760s, Alexandria’s Presbyterians began holding services at the Assembly Hall. Later, they constructed a Meeting House on South Fairfax Street, adjacent to their burial ground. The burial ground is notable for containing one of the oldest known graves in the area, dating back to 1761. [More on the Presbyterian Meeting House Burial Ground].

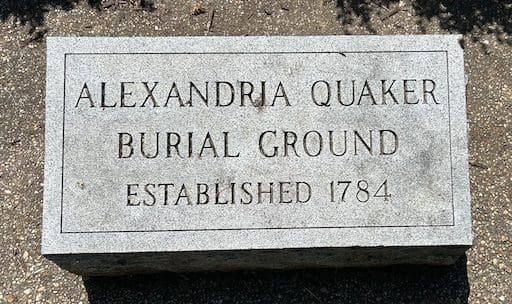

The Quaker Burial Ground

In 1784, Quakers established a burial ground on Queen Street, later relocating burials to the Friends cemetery in the District of Columbia in 1809.[Read about the Quaker Burial Ground’s history].

Alexandria’s Burial Evolution and Urban Development

St. Mary’s Catholic Church: A Historical Cornerstone

Founded in 1795, St. Mary’s Catholic Church, now the Basilica of Saint Mary, established Virginia’s first Catholic burial site. By 1803, William Thorton Alexander had generously donated the land where the initial Catholic Church was located. After 1810, the church moved to a new site at the 300 block of S. Royal Street, land originally occupied by the first Methodist Church in Alexandria, known as Trinity. Today, the cemetery at 1000 S. Royal Street, Alexandria, VA 22314, stands as Virginia’s oldest Catholic Cemetery, embodying a rich history deeply interwoven with the community’s fabric. [Discover St. Mary’s Cemetery].

The Experiences and Burial Practices of Enslaved and Freed African Americans

Alexandria initially set aside ‘Penny Hill’ as its primary municipal burial ground, predominantly for the enslaved, freed African Americans and those unaffiliated with any religious denomination. [Discover Penny Hill Cemetery]

Municipal and Epidemic Response Developments

The 1803 yellow fever epidemic prompted significant changes in the city’s approach to public health and burial practices, leading to the creation of the [Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex]. This new site addressed the urgent need for more structured and sanitary burial options amidst the health crisis.

Preserving Alexandria’s Historical Burial Sites

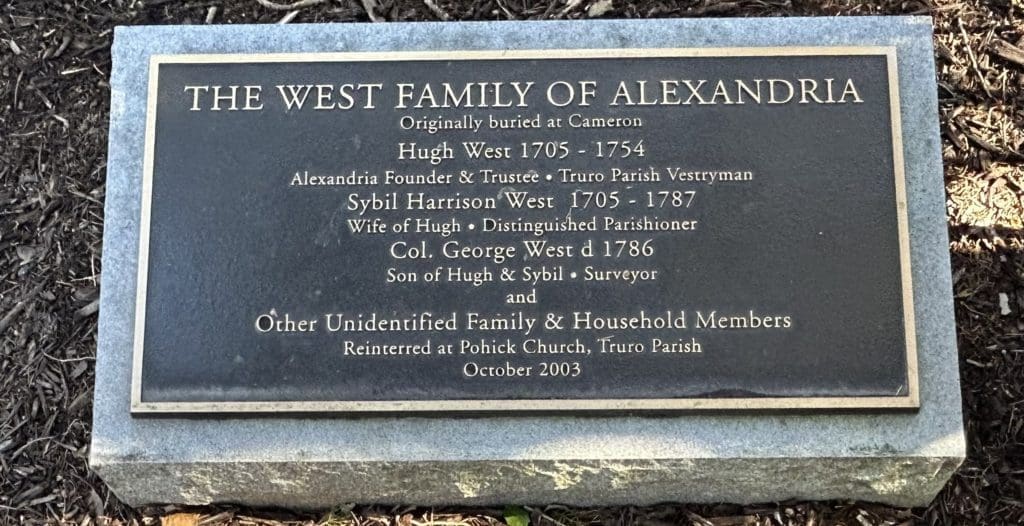

The Archeological Protection Ordinance of 1989 mandates archaeological digs before construction in certain zones. This has led to the discovery of previously lost family cemeteries, like the West Family burial ground.

Conclusion

Today, Alexandria’s historical sites, including 18th-century burial grounds at Christ Church, The Old Presbyterian Meeting House, St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, and the site of the former Quaker Burial Ground, now home to The Kate Waller Barrett Library, reflect the profound influence of religious, political, and social changes on the city’s burial customs. These sites, which are central to the community’s history, offer a window into the lives of the city’s early inhabitants and their practices around life and death.

As visitors walk through Old Town’s historic streets and explore these significant sites, they encounter tangible reminders of the beliefs, lives, and deaths that have shaped this vibrant community. Alexandria’s graveyards and historical markers stand as enduring testaments to its journey from a tobacco hub to a bustling colonial center and its pivotal role during the Civil War and beyond.

Sources of Information

Lancaster, R. A. (1915). Historic Virginia Homes and Churches. J. B. Lippincott and Company.

The Alexandria Association. (1956). Our Town: 1749 – 1865. Likenesses of This Place & Its People Taken from Life by Artists Known and Unknown. Dietz Printing Company.

Sengel, W. R. (1973). Can These Bones Live? Kingsport Press.

Neherton, N., Sweig, D., Artemel, J., Hickin, P., & Reed, P. (1978). Fairfax County, Virginia A History. Fairfax County Board of Supervisors.

Smith, W. F., & Miller, T. M. (1989). A Seaport Saga, Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia. The Downing Company Printers.

Pippenger, W. E. (1992). Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volumes 3. Family Line Publications.

Greenly, M. (1996). Those Upon the Curtain Has Fallen: The Past and Present in Old Town Alexandria, VA. Alexandria Archaeology Publications.

Wells, K. J. (1997). Reflections of Social Change: Burial Patterns in Colonial Fairfax County, Virginia. College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences. [Paper 1539626090].

Powell, M. G. (2000). The History of Old Alexandria, VA, from July 13, 1749 – May 24, 1861. Willow Bend Books. (Index by Pippenger, W. E.)

Ricks, M. K. (2007). Escape on the Pearl. The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad. Harper Collins Publishers.

Ring, C. K., & Pippenger, W. E. (2008). Alexandria, Virginia Town Lots 1749 – 1801 together with Proceeding of the Board of Trustees 1749 – 1801. Heritage Books.

Crothers, A. G. (2012). Quakers Living in the Lion’s Mouth. The Society of Friends in Northern Virginia, 1730 – 1865. The University of Florida Press.

Dahmann, D. C. (2002). The Roster of Historic Congregational Members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. [Unpublished manuscript].

City of Alexandria. (2020). Official Website. [Webpage].

Alexandria Archeology. (2022). Site Report for Hoffman Town Center Blocks 4 & 5. [Web report].

City of Alexandria Archeology. (2022). 1989 Archeology Protection Code. [Webpage].

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. (2023). [Official site].

Mitchell, B. (1987). Map of 1760 Fairfax County, Virginia landowners. Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning. [Edited by D. M. Sweig].

The Fireside Sentinel. (1987). The Alexandria Library, Lloyd House Newsletter, 1(7). Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library.

Bill of Rights Institute. (n.d.). Virginia statute for religious freedom. Retrieved April 23, 2024, from https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/virginia-statute-for-religious-freedom