Discover the stories of valor and sacrifice at Alexandria National Cemetery, one of America’s most historic resting places, just miles from the nation’s capital.

Entrance to the Alexandria National Cemetery on Wilkes Street, approximately 1865. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Introduction

Nestled within the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, Alexandria National Cemetery is a testament to America’s past. Established in 1862, it predates Arlington National Cemetery and serves as the final resting place for over 4,230 individuals whose lives shaped American history. This cemetery honors those who served our nation, telling stories of courage, sacrifice, and unity.1

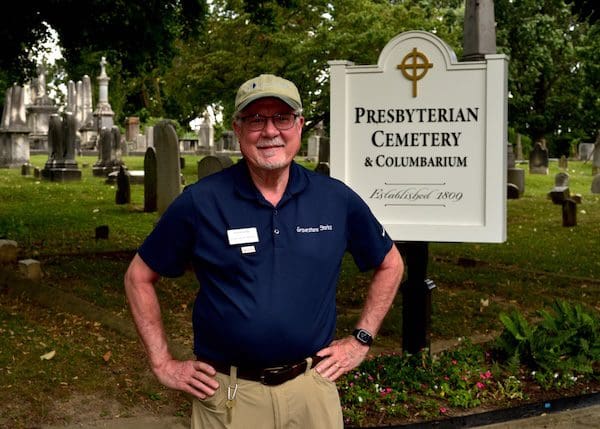

This page represents years of original research, archival study, and on-the-ground documentation conducted by public historian David Heiby.

The Strategic Importance of Alexandria

Located just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., Alexandria was among the first Confederate towns to fall to Union forces, being occupied in May 1861. The city quickly became a key logistical hub for the Union Army, supporting the eastern campaigns with its proximity to the capital and its robust transportation network. By 1862, Alexandria was not only a fortified town but also a medical and supply center, with over 30 hospitals established to care for the Union’s wounded and ill soldiers.

For those interested in exploring the locations of Alexandria’s various Civil War hospitals, the Office of Historic Alexandria provides a comprehensive map resource [link].

The Founding of Alexandria National Cemetery

In response to the rising death toll among soldiers stationed in and around Alexandria, the City of Alexandria purchased two acres of land from John H. and Margaret Baggett for $800 on June 1, 1862. A month later, Congress passed an act authorizing the establishment of national cemeteries for soldiers who had died during the conflict, and Alexandria National Cemetery became one of the first to be established. It was originally known as the Soldier’s Cemetery.

The cemetery was initially leased to the federal government for 999 years for $1.00. In 1875, the City fully transferred the property to the federal government. Following this, significant improvements were made, including replacing the cemetery’s original wooden headboards with stone markers, ensuring the permanence and dignity of the soldiers’ graves.

Alexandria’s Role as a Hospital Hub

During the Civil War, Alexandria became a vital Union hub for medical care, housing over 30 hospitals to treat the wounded. Homes, churches, and public buildings were converted into hospitals, including Grosvenor Branch (housed in the Lee-Fendall House) and L’Ouverture Hospital, which were critical in treating white soldiers and the United States Colored Troops. These hospitals were pivotal in caring for soldiers, and many of the deceased were laid to rest in the newly established military cemetery.

The Expansion of Alexandria National Cemetery During the Civil War

As the war progressed, Alexandria’s Civil War hospitals treated a diverse patient population, including wounded Union soldiers from both white and black regiments, Confederate prisoners of war, and African American refugees who had escaped slavery and sought refuge behind Union lines. However, it’s important to note that at this time, the Soldier’s Cemetery (also known as the Military Cemetery), which later became the Alexandria National Cemetery, was reserved primarily for white Union soldiers and Confederate prisoners of war who died in Alexandria. The United States Colored Troops (USCTs) and African American refugees who died were initially buried in the separate Freedmen’s and Contrabands Cemetery on S. Washington Street.

This surge of casualties led Quartermaster James Grafton Carleton Lee, the Union Quartermaster for Alexandria, to request authorization in March 1864 to purchase additional land “375 ft in length by 249 ft in width” at the same rate of $400 per acre as the original purchase for the Alexandria National Cemetery. This expansion would add approximately 90,000 square feet, or just over 2 acres, effectively doubling the size of the existing 2-acre cemetery.

Lee anticipated that the existing two-acre cemetery would reach capacity within two weeks of the end of March, further underscoring the critical need for expansion to accommodate the growing number of fallen Union soldiers from white regiments.

Debates Over Burials and the Continued Use of Alexandria National Cemetery

As the war continued and casualties mounted, there were initial plans to discontinue burials at the Alexandria National Cemetery and instead transport deceased soldiers to the newly established Arlington National Cemetery, located just five miles north in Arlington, Virginia. However, Surgeon Edwin Bently, U.S. Volunteers in charge of the 3rd Division General Hospital in Alexandria, objected to this proposal in a letter dated May 24, 1864, addressed to Captain Lee, the Quartermaster. Bently cited the “great inconvenience and expense” of transporting the fallen soldiers and argued that “the distance of transportation would prevent the attendance of escort or chaplain and also the military burial to which every soldier is entitled, and the expectation of which often soothe the last hours of a soldier’s life.”

Increased Burials and the Cemetery’s Enduring Role

As a result of Bently’s objections, burials continued at the Alexandria National Cemetery, while Arlington National Cemetery served as an additional burial site for the growing number of fallen soldiers. Pippinger’s statistical analysis, as detailed in Volume 5 of his work “Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia” (2014), reveals that 1,537 soldiers (all white) were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery before 1864. During 1864-1865, an additional 1,717 burials took place, including 229 Black soldiers and 1,488 white soldiers.

These figures demonstrate that Alexandria National Cemetery remained an active burial site throughout the war, even after Arlington’s establishment, with the number of interments actually increasing in the final years of the conflict. Pippinger’s research also shows that the cemetery continued to receive Civil War-related burials in the immediate post-war period, with 13 additional Civil War era interments occurring from 1866 to 1869. Notably, Union soldiers account for 77% of all burials in the cemetery, underscoring its primary role as a resting place for those who fought for the Union cause.

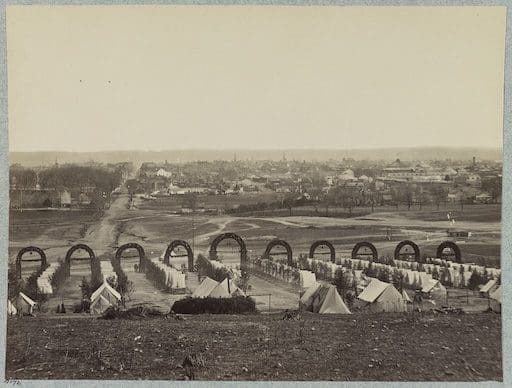

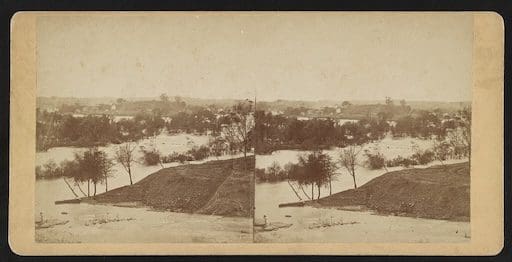

This historic photograph, taken from what was then known as West Village across Hooff’s Run, provides a rare Western perspective of Alexandria National Cemetery during the final year of the Civil War. The image captures the cemetery at a time when burials had surged due to the continuing conflict, including the reinterment of United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers in early 1865. In the distance, the entrance arch can be seen, though its inscription is not visible from this angle. The large open field in the foreground highlights how undeveloped the surrounding area remained at the time. The vantage point was likely along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, near what is now the 1800 block of Jamieson Avenue. This image serves as a valuable visual record of the cemetery’s early years and its role as a final resting place for thousands of Union soldiers.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Relationship with Arlington National Cemetery

Though Alexandria National Cemetery was established in 1862, predating Arlington National Cemetery by two years, both burial grounds were critical in addressing the growing number of Union casualties. In 1864, the newly created Arlington National Cemetery, just five miles north of Alexandria on the grounds of Robert E. Lee’s family estate, quickly became a prominent national burial site. On May 13, 1864, Private William Christman of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry became the first military member interred there.(For more on this soldier’s poignant tale, see [http://www.tobyhannatwphistory.org/assets/WilliamChristmanHistory.pdf])

While Arlington emerged as a symbol of national loss, Alexandria National Cemetery remained a vital burial site throughout the war, particularly for soldiers who died in the many hospitals surrounding Alexandria. This local proximity allowed for timely burials, often attended by fellow comrades and chaplains.

In many ways, Alexandria National Cemetery served as a local resting place for Union soldiers who had fought and died in the hospitals surrounding the city, while Arlington emerged as a national symbol of the war’s toll. Both cemeteries, though different in scale and prominence, tell parallel stories of sacrifice and loss during the Civil War.

The Story of Corporal William H. H. Marsh

Corporal Marsh’s Enlistment and Service

Corporal Marsh’s story provides a poignant example of the sacrifices made during this period. He enlisted in Calais, Vermont, on September 3, 1861, and showed his dedication to the cause by reenlisting on December 15, 1863. His service was marked by promotion to Corporal on November 4, 1862.

The Battle of the Wilderness

Marsh was mortally wounded during the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-6, 1864), a brutal engagement that occurred in a densely wooded area south of the Rapidan River in Virginia. This battle, which resulted in over 28,000 casualties, was fought in a second-growth forest of pine trees, brush, and shrubs that made combat incredibly challenging and deadly.

The horrific nature of this conflict was vividly described by Lt. Col. Horace Porter of Grant’s staff: “Forest fires raged; ammunition trains exploded; the dead were roasted in the conflagration; the wounded, roused by its hot breath, dragged themselves along, with their torn and mangled limbs, in the mad energy of despair, to escape the ravages of the flames; and every bush seemed hung with shreds of blood-stained clothing….” (Rhea, 2004, pp. 451-452)

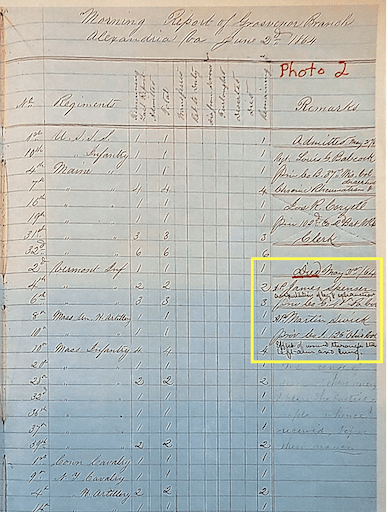

Marsh’s Final Days and Burial

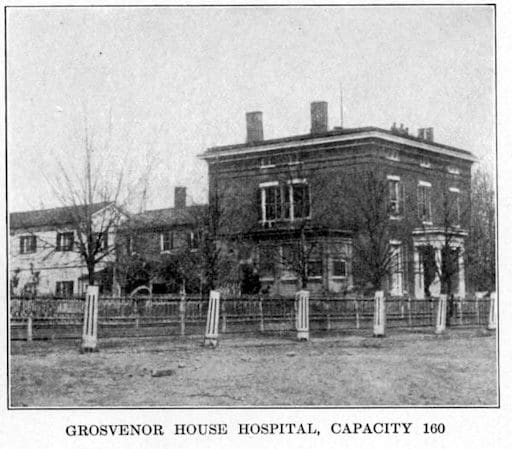

Marsh was admitted to the Grosvenor Branch Hospital (Lee-Fendall House) on May 27, 1864, with a gunshot wound to his left hip. Despite medical efforts, he succumbed to his injuries on July 2, 1864, although his gravestone erroneously states July 1, 1864. This discrepancy between official records and the gravestone inscription serves as a reminder of the challenges in maintaining accurate records during the chaotic times of war. Marsh’s final days in the hospital and his burial in Alexandria National Cemetery reflect the somber realities faced by the thousands of soldiers interred there.

The Burial of USCT Soldiers and the Fight for Equality

A Groundbreaking Civil Rights Protest

In December 1864, a significant moment in civil rights history unfolded at Alexandria National Cemetery. Initially, African American soldiers were segregated from their white counterparts, being interred in the Freedmen’s Cemetery (also known as the Contraband Cemetery). However, this practice was challenged when 443 African American soldiers, recovering at L’Ouverture Hospital, signed a petition demanding burial alongside their white comrades. This act of protest is considered one of the earliest recorded civil rights demonstrations in the United States.

Desegregation of the Cemetery

The soldiers’ petition did not go unheeded. In response to their calls for equality, Union Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs took action. By January 1865, he had overseen the disinterment and reburial of 118 United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers from the Contraband Cemetery into Alexandria National Cemetery. This decision marked a pivotal moment, as it made Alexandria National Cemetery the first integrated federal military burial ground in the country.

Official Recognition and Documentation

On January 22, 1865, Meigs sent a comprehensive report to Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War. The report included a detailed list of those buried in the cemetery, with Meigs requesting 2,000 copies for distribution. The breakdown of burials at that time was as follows:

- White Soldiers: 3,367

- US Navy: 2

- White Citizens: 1

- White Females: 2

- Colored Soldiers: 229

Legacy and Current Status

Today, the number of United States Colored Troops laid to rest in Alexandria National Cemetery has grown to 249. This increase reflects the ongoing recognition and honor bestowed upon these brave soldiers who fought not only for their country but also for their right to equal treatment in death.

The cemetery continued to expand over time, accepting new burials until 1967. Currently, it is considered closed, with no additional space available for new interments. However, it stands as a lasting testament to the bravery of all soldiers and the fight for equality that began even before the Civil War had ended.

In 1871 the Superintendent’s Lodge was built to serve administrative needs. However, just seven years later a fire severely damaged the building. Under General Montgomery Meigs, a new Seneca red sandstone lodge was constructed in 1887. More recent key developments include the closing of the cemetery in 1967, though some sections were reopened in later decades to inter cremated remains of eligible veterans and dependents.

Today, the Alexandria National Cemetery serves as a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made during the American Civil War. It is the final resting place for over 4230 individuals, many of whom were Union Soldiers who bravely engaged in the conflict. Significantly, 249 members of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) are also interred here, underscoring the diverse array of individuals who shaped the nation’s history.

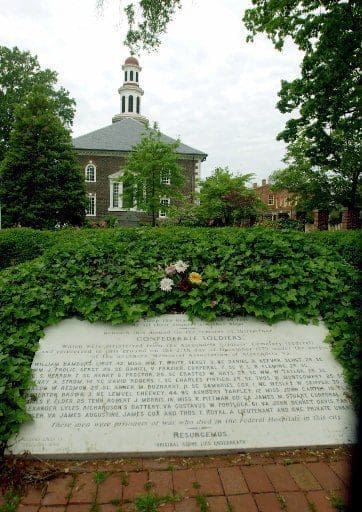

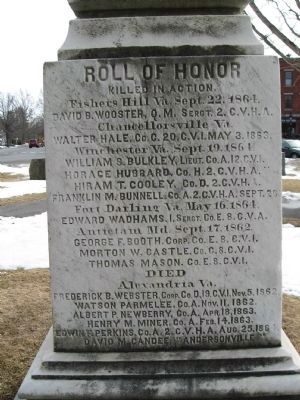

Confederate Presence and Daughters of the Confederacy

Although the primary focus of the cemetery is on honoring Union Soldiers, a noteworthy chapter of its history pertains to the burial of Confederate prisoners of war. However, in 1879, the Daughters of the Confederacy took the initiative to oversee the relocation of these soldiers’ remains. The majority were reinterred in a communal grave at Alexandria’s revered Christ Church burial ground on North Washington Street. As a result, no Confederate soldiers are interred within the confines of the cemetery.

The Evolution of Gravestones

The gravestones in Alexandria National Cemetery reflect the transition from temporary markers to lasting memorials, symbolizing the nation’s enduring commitment to honoring its fallen heroes.

In the early years, wooden headboards were used to mark graves, but these proved unsustainable and required frequent replacement. Over time, stone markers were introduced, providing a more durable tribute to those interred.

The design of these markers evolved into standardized “Civil War”-type headstones, with rounded tops and carved shields bearing the soldier’s name, company, and regiment. This shift to permanent gravestones underscores the importance of preserving the memory of those who served, ensuring their legacy endures for future generations.

Heroes and History: The Lives Behind the Stones

Alexandria National Cemetery is a lasting tribute to the courage, sacrifice, and dedication of the men and women who served our nation. Within its grounds lie countless stories of bravery, resilience, and patriotism, from the Civil War to modern times. Each headstone marks a life that contributed to the fabric of American history, from skilled sharpshooters and those lost in tragic wartime accidents to the courageous members of the United States Colored Troops. These stories, etched in stone, remind us of the sacrifices made by those who served, ensuring that their legacies endure for generations to come.

George Fermane, Elite Marksman of the Civil War

Private George Fermane, who rests in The Alexandria National Cemetery, met his fate on August 17, 1862. He served as a United States Sharpshooters (USSS) member during the American Civil War. This corps of soldiers was instrumental in the Union Army and consisted of the First and Second Regiments of United States Sharpshooters.

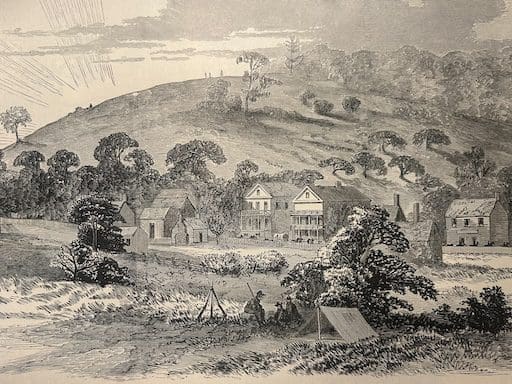

Early in the war, the United States Sharpshooters (USSS) were used near Alexandria to spy on and scout the Confederates, especially at Munson’s Hill (Falls Church). As the armies moved, they were deployed at Falmouth (opposite Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock) and during the Peninsula Campaign. They were also effective in the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, and saw action at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

The USSS held a rigorous standard for entry, demanding that volunteers pass a challenging marksmanship test. To qualify, they needed to achieve a remarkable feat: stringing together ten consecutive shots within a ten-inch-wide target from 200 yards.

Patterned after the legendary British Green Jackets of the Napoleonic War, the U.S. Sharpshooters owed their creation to the visionary Colonel Hiram Berdan. Throughout the conflict, they proved themselves to be exceptional soldiers. Clad in dark green caps, coats, and pants and equipped with leather gaiters, their uniforms lacked the telltale shine of brass buttons, buckles, or insignia. This deliberate choice ensured their camouflage in the theater of guerrilla-style warfare, a mode of combat they had mastered. Armed with the Sharps 1859 breech-loading target rifle, the USSS could swiftly load and fire from various positions – prone, standing, or even perched in trees – at a rate of fire three times that of standard rifles. The Sharps exhibited a terrifying accuracy of up to 600 yards, remaining deadly beyond that range. The sharpshooters aggressively maneuvered into advantageous firing positions in battle, often targeting high-value adversaries such as officers or artillerymen.

While the unit to which Private George Fermane belonged remains shrouded in mystery, as do the circumstances of his demise, his legacy as a member of the USSS underscores his courage and commitment to a nation torn by civil strife.

Charles W. Needham: Cavalryman Felled at Aldie

A Massachusetts native, he enlisted on August 7, 1862, at age 24, in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment. His journey soon began as Private Needham committed to the Union cause in a nation divided. His courage would face testing in the crucible of battle.

On June 17, 1863, Needham’s regiment engaged in combat at Aldie, Virginia, as part of a five-day clash in the Loudoun Valley. This fierce fighting resulted in over 1,400 casualties (killed, wounded, missing, or captured), as well as the loss of thousands of horses. Union commander Joseph Hooker was desperately trying to gather intelligence on the whereabouts of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army, which was moving north during its second invasion of the North. The opposing cavalry forces clashed repeatedly as the Confederates sought to conceal their maneuvers. This campaign would ultimately culminate in the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg from July 1-3, 1863.

Eyewitness accounts describe Needham’s steadfast bravery amidst the chaos as he charged ahead boldly on horseback. But a horrific head wound halted his advance permanently.

Badly wounded, Needham endured a grueling transport along with others injured by an Ambulance wagon to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. From there, they were moved by rail into Alexandria, where Needham was admitted to Grosvenor Branch, a Union Army hospital housed in the Lee-Fendall House, clinging to life. Despite valiant medical efforts, his condition worsened over the next two weeks. Needham finally succumbed on June 30, 1863, at just 25 years old.

Needham was buried in Alexandria National Cemetery, known then as “Soldier’s Cemetery”. His sacrifice solemnly underscored the devastating cost of war. Needham gave his life for the union and country. His courage and selflessness etched for eternity beside the weathered gravestones of patriots who also gave their last full measure. To explore deeper into the history of the Battle of Aldie and the details on the first Union monument dedicated on Southern soil, please read the blog post: [The First Union Regimental Monument south of the Mason-Dixon Line].

Nehemiah Metlock: A Soldier’s Journey from the 113th Ohio to the Veteran Reserve Corps

The stories of soldiers like George Fermane and Charles W. Needham highlight the bravery and sacrifice of those who fought and died in the heat of battle. However, the tale of Nehemiah Metlock serves as a reminder that not all soldiers’ contributions were made on the front lines. Metlock’s journey from the 113th Ohio Infantry Regiment to the 12th Veteran Reserve Corps showcases the vital role played by those who, despite injury or illness, continued to serve their nation in whatever capacity they could.

Nehemiah Metlock (sometimes spelled “Matlock”) is a Union soldier buried in the National Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia. Born in 1814 in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, Metlock later moved to Franklin County, Ohio, where he married Hester Wilson in 1840. The couple had six children, including their eldest son, John W., who fought in the Civil War as a 60th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI) Company C member.

Metlock enlisted in the Union Army on August 13, 1862, at 46, joining the 113th Ohio Infantry Regiment. The 113th Ohio participated in numerous key battles throughout the war, such as Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, and Sherman’s March to the Sea.

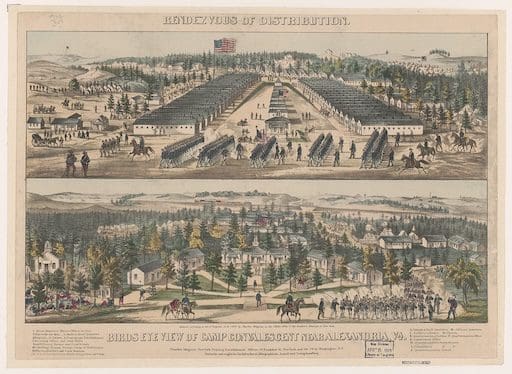

At some point during his service, Metlock was injured or fell ill and was likely sent to Camp Convalescent near Alexandria, Virginia. This camp was established to care for recovering soldiers who were not well enough to return to their units but no longer required hospitalization. Many of the men who spent time at Camp Convalescent later joined the Veteran Reserve Corps (VRC), a unit established to utilize partially disabled soldiers for light-duty tasks.

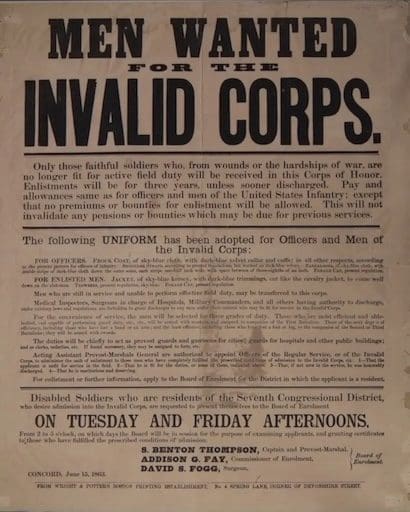

Initially known as the Invalid Corps, the unit was created during the Civil War to use convalescent soldiers for non-combat roles such as guarding, instructing, and hospital duties. However, confusion with the damaged goods stamp “I.C.” (inspected-condemned) affected volunteer morale, leading to the corps being renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps on March 18, 1864.

This recruiting poster, sourced from the National Library of Medicine’s online exhibition “Life and Limb: The Toll of the American Civil War” (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/lifeandlimb/honorablescars.html), showcases the Invalid Corps, which was later renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps.

Members of the VRC were often men unfit for active duty but capable of light work. The unique uniform featured a sky-blue jacket with dark blue trimmings and sky-blue trousers. However, soldiers objected to the uniform, finding it stigmatizing and demoralizing. Despite these challenges, the VRC continued to serve vital supportive roles throughout the war, despite their disabilities.

The concept of utilizing soldiers with disabilities for essential non-combat roles had historical precedent. During the American Revolutionary War, Lewis Nicola commanded the Invalid Regiment, established in 1777. This unit was a precursor to later formations like the Civil War’s Invalid Corps and Veteran Reserve Corps. Nicola’s innovative approach set an important precedent in American military history. Interestingly, Lewis Nicola who commanded the Invalid Regiment during the American Revolutionary War, is buried in the Old Presbyterian Meeting House 18th-century burial ground just one mile east of the Alexandria National Cemetery.

As part of the 12th VRC, Metlock was likely involved in the defense of Washington, D.C., during Confederate General Jubal Early’s attack on Fort Stevens in July 1864. The VRC played a crucial role in repelling the Confederate assault, marking the only time a sitting U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, came under direct enemy fire.

Tragically, Nehemiah Metlock died on September 14, 1864, in Alexandria, Virginia. While the circumstances surrounding his injury and subsequent death remain unknown, his service and sacrifice as part of the Union Army and the Veteran Reserve Corps are remembered through his burial in the National Cemetery.

Private Solomon Williams: Fatally Wounded at Bristoe Station

Private Solomon Williams, a young soldier of just 20 years, bravely fought in the Battle of Bristoe Station on October 14, 1863, in Prince William County, Virginia. Serving with dedication in the 140th PA Volunteers, Company E, he played a role in this crucial Civil War confrontation. Despite being outnumbered by Confederate Lieutenant A.P. Hill’s larger forces, the Union troops achieved victory through a swift ambush. Regrettably, during the heat of the battle, Private Williams was severely injured, receiving a gunshot wound to his upper right arm.

He was admitted to Grosvenor Branch, a Union Army hospital housed in the Lee-Fendall house. Faced with the severity of his injury, the medical team had no choice but to amputate his arm. Private Williams’ condition deteriorated despite their efforts, and he tragically died from pyemia, or blood poisoning, on October 31, 1863. He was buried in Section A, Site 1037. His story serves as a testament to the bravery and sacrifices made by many during the Civil War.

Alton Hawkes: Brief Life, Enduring Sacrifice

Alton Hawkes enlisted in the Union’s 76th New York Infantry, Company A, on August 17, 1863. The regiment had already seen action at the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862, where they suffered heavy losses against extreme odds. Only 40 men remained, with 4 killed. Sergeant Stamp gave his life heroically protecting the colors, and after Colonel Wainwright fell injured, leadership passed to First Lieutenant Crandall. The 76th New York Infantry also fought at the Battle of Antietam, playing a crucial artillery support role despite casualties.

Hawkes joined the regiment nearly a year after these battles. His own war contribution proved tragically brief. He contracted acute laryngitis and diphtheria that winter. As his condition worsened, Hawkes was admitted to Alexandria’s Grosvenor Branch hospital—the converted Lee-Fendall House. But the valiant care there could not prevent the inevitable. Alton Hawkes perished on January 12, 1864, only months after dedicating himself to the Union cause.

The 21-year-old now rests among other fallen comrades in Plot 1278 of Alexandria National Cemetery—his lasting memorial a poignant reminder of lives cut short for freedom.

The Lee-Fendall House, also known as the Grosvenor Branch Hospital during the Civil War, witnessed the final moments of 104 Union soldiers out of the many admitted during the conflict. An exhaustive study of the Grosvenor Branch Hospital records by volunteers and staff revealed this sobering fact. Among the countless mortally wounded troops were Needham, Williams, Hawkes, and Swick, whose fates intertwined with the mansion-turned-hospital. Of the 104 patients who perished, 51 are now buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery. After they passed away, their bodies were moved to a temporary morgue, referred to as the “dead house,” constructed in the garden of the Grosvenor Branch, where they remained until transported for burial. The gravestones of these Union soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery stand as a reminder of the steep price paid by soldiers and surgeons alike during the Civil War.

The Grosvenor House Hospital, once located at 414 N. Washington Street in Alexandria, Virginia, was built around 1830. Seized during the Civil War, it was used as a hospital for wounded soldiers, with the nearby Lee-Fendall House serving as a branch or annex. After the war, the Grosvenor House became the home of Confederate Brigadier General Montgomery Dent Corse and, later, local merchant and druggist Clarence C. Leadbeater. In the early 1960s, the house was demolished to make way for an office building, leaving only the Lee-Fendall House standing.

After the war, the Lee-Fendall House returned to being a private residence, remaining in the Lee family until it was sold to Robert Downham in 1903. Downham, a prominent Alexandria liquor purveyor, lived there until Prohibition. In 1937, labor leader John L. Lewis moved in and lived there during his career’s peak. After Lewis died in 1969, the Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation (VTHP) purchased the house and opened it as a museum in 1974.

The Lasting Impact of the Mine Run Campaign: From Private James Luman to ‘I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day”

Private James Luman, a 27-year-old soldier from the 122nd Ohio, was severely wounded with a gunshot to the head during the Battle of Mine Run on November 27, 1863. He was admitted to the Grosvenor Branch Hospital (Lee-Fendall House) on December 8, 1863, where he died eight days later, leaving behind his widow, Mary.

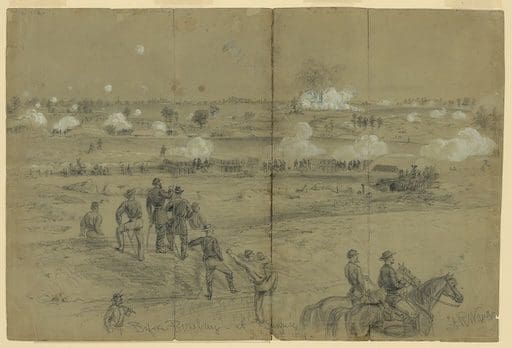

The Mine Run Campaign, General Meade’s final attempt to destroy Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia before winter, ultimately failed. Meade had planned to strike the right flank of the Confederate Army but was delayed by logistical issues. This allowed Lee to react and fortify his positions along Mine Run. After assessing the strength of the Confederate line, Meade concluded that it was too strong to attack and withdrew his forces, ending the campaign inconclusively.

Interestingly, the Battle of Mine Run profoundly impacted American literature. Upon learning that his son, Charles Appleton Longfellow, had been severely wounded in the battle, the renowned poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote “Christmas Bells” in 1863. This poem later became the basis for the famous Christmas carol “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” forever linking the battle to a message of hope and peace amidst the tragedy of war.

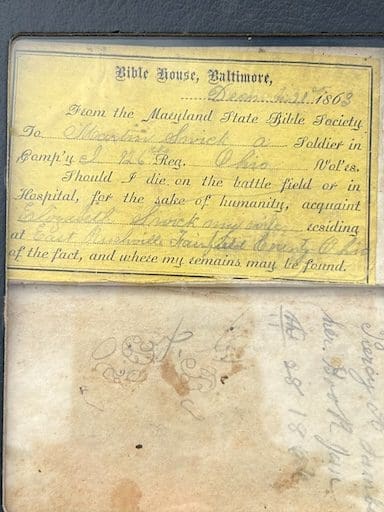

Martin Swick: An Ohio Soldier Mortally Wounded at Spotsylvania

Among the countless stories etched in stone at Alexandria National Cemetery, the tale of Martin Swick, a soldier from Fairfield County, Ohio, serves as a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by so many during the Civil War. Swick’s journey, from his enlistment in the 126th Ohio Infantry to his final resting place in grave A: 816-60, is a testament to the bravery and resilience of those who fought to preserve the Union.

During the Gettysburg Campaign, Swick was captured on June 14, 1863, at the Battle of Martinsburg, Virginia. He was confined in Richmond, Virginia, likely at Belle Isle Prison, on June 23, 1863. After being paroled on July 8, 1863, he returned to his regiment on October 5, 1863.

On April 7, 1864, Swick was reduced in rank from Corporal to Private. He narrowly escaped capture at the Battle of the Wilderness when Gordon’s Brigade outflanked the 6th Corps. However, on May 12, 1864, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, Swick suffered a gunshot wound to his left rear shoulder and lung. He succumbed to his injuries on May 31, 1864, at The Grosvenor House Branch in Alexandria, Virginia.

Martin Swick left behind his wife, Elizabeth (Harper) Swick, and possibly as many as four children. He is buried in grave A 816-60 in the Alexandria National Cemetery. One of his descendants, Brent Reidenbach, possesses the bible that Martin carried with him during the war. Brent has also visited Martin’s grave several times, paying respects to his ancestor who sacrificed his life during the Civil War.

The Fort Lyon Powder Magazine Explosion

On June 9, 1863, a catastrophic explosion at Fort Lyon, located just outside Alexandria, sent shockwaves through the city. The accidental ignition of eight tons of gunpowder and ammunition caused a blast that shattered windows as far away as Georgetown. Twenty-one soldiers from the 3rd New York Heavy Artillery were killed instantly, and several more succumbed to their injuries in the following days. They were laid to rest side by side at Alexandria National Cemetery, a solemn reminder of the dangers soldiers faced not only in battle but also in everyday military duties.

The story of these brave soldiers and the tragic incident they faced can be explored further in [The Sad Fate of the New York Volunteers] blog.

They gave their lives in service to their nation and now rest for eternity on the solemn grounds of Alexandria National Cemetery. The tragic accident that claimed them will never be forgotten, memorialized by the very gravestones that mark where they lay.

The Heavy Toll of War: Watson Parmalee’s Tragic End

Private Watson Parmalee’s story is a poignant reminder of the devastating impact of the Civil War on the mental health of soldiers. Laid to rest in Section A, Plot 446 of the Alexandria National Cemetery, Parmalee’s life came to a tragic end after three arduous weeks in an Alexandria, Virginia hospital. The young soldier had been consumed by the overwhelming fear of being killed in battle, worrying himself to the point of physical illness. Despite never facing combat directly, the psychological toll of the war proved too much for Parmalee to bear, and he succumbed to his mental anguish on November 11, 1862.

Parmalee’s passing was movingly recounted by Lewis Bissell, a comrade from the same company, who noted that Parmalee was consumed by his concerns, ultimately leading to his demise. (Mark Olcott with David Lear, The Civil War Letter of Lewis Bissell, A Curriculum, The Field School Educational Foundation Press, Washington, D.C., 1981, Pg. 30).

On the day of his departure, Parmalee was laid to rest in the Alexandria National Cemetery, surrounded by his fellow company members in a somber burial ceremony. The ceremony concluded with three volleys of rifle fire resonating over his grave, a final tribute to a soldier who paid the ultimate price for his service.

(Private Frederick A. Olroyd from Litchfield, Connecticut, an ancestor of the owner of Gravestone Stories, served in the same regiment as Watson Parmalee – the 2nd Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery Regiment. Specifically, Olroyd was in Company D of this regiment. He enlisted in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on September 5, 1864. Olroyd fought at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864. His service concluded with an honorable discharge on July 7, 1865, at Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia, located at what is now 4348 Old Glebe Road in Arlington, Virginia.)

William L. Phillips: An Alabama Unionist’s Journey in the Civil War

The Alexandria National Cemetery is the final resting place of Private William L. Phillips, a soldier who served in the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment during the American Civil War. This regiment was unique among Union forces, primarily composed of Southern Unionists from Alabama who chose to fight for the Union cause despite their state’s secession. The 1st Alabama Cavalry was the only predominantly white Union regiment from Alabama, with 2,066 of the 2,678 white Alabamians who enlisted in the Union Army serving in its ranks.

Phillips’ gravestone is a testament to his service and the complex loyalties that divided many Southern states during the war. His story, along with that of his regiment, highlights the often-overlooked roles played by Southerners who remained committed to the Union in the face of secession and conflict.

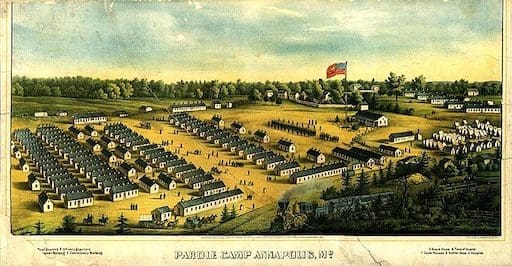

William L. Phillips himself was part of this regiment, embarking on a temporary assignment under the command of Colonel Abel D. Streight during the raid across northern Alabama from April 19 to May 3, 1863. His journey with this command ultimately led to their surrender in Rome, Georgia, on May 3, 1863. After his capture, Phillips was sent to Richmond, VA as a prisoner of war. Following his parole, he was transferred to the Union parole camp at Parole, MD, and then, for reasons unknown, to Camp Chase in Ohio, which was primarily a Union prison camp for Confederates. His final transfer was to the Slough General Hospital in Alexandria, VA, where he died on May 21, 1865.

In addition to his military service, William L. Phillips was a family man, the son of William and Nancy B. (Chick) Phillips. On December 29, 1853, he entered into matrimony with Salena Bannister, the daughter of James and Martha (Deverix) Bannister, in Forsyth County, Georgia. Their union brought three children: Martha Virginia, Lewis Lafayette, and James William. Tragically, William’s life was cut short during the Civil War, and his final resting place is now in the Alexandria National Cemetery. The cause of his untimely death is recorded as a cyanide overdose, marking a poignant chapter in the history of this unique Union regiment from Alabama.

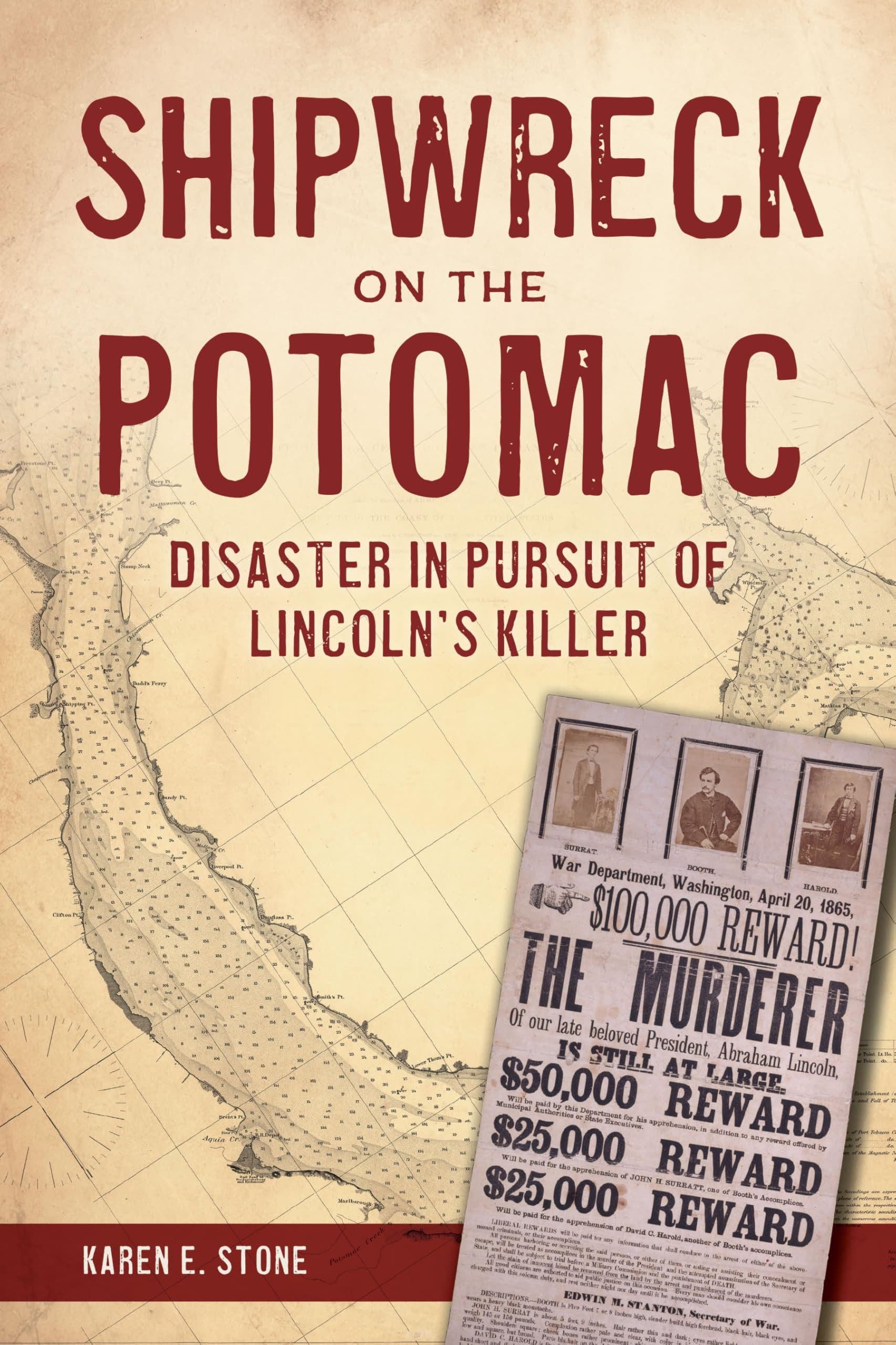

A Hidden Chapter in Civil War History: The Black Diamond Tragedy

In the shadow of Lincoln’s assassination, a lesser-known tragedy unfolded on the Potomac River. In the early hours of April 23, 1865, as the nation mourned its fallen leader, four brave civilian volunteers from the U.S. Quartermaster Department made the ultimate sacrifice.

Peter Carroll, Samuel N. Gosnell, George W. Huntington, and Christopher Farley – names etched in stone at Alexandria National Cemetery – were among 87 souls lost when a large sidewheel steamer, known as the “Massachusetts,” collided with the coal barge “Black Diamond” on the Potomac River.

But what brought these civilians into harm’s way during one of America’s most tumultuous periods? What connection did their fate have with the hunt for Lincoln’s assassin?

A granite boulder standing sentinel near the cemetery’s flagpole hints at a story far more complex than its simple inscription suggests. It’s a tale of duty, sacrifice, and unforeseen consequences in the pursuit of justice.

Uncover the full, gripping narrative in our blog: [The Black Diamond Disaster: Civilian Lives Lost in the Hunt for Lincoln’s Assassin]

Dive into this overlooked chapter of Civil War history and discover how the ripples of one fateful night on the Potomac touched lives far beyond the water’s edge.

United States Colored Troops (USCT): Honoring Their Legacy at Alexandria National Cemetery

Before the Civil War, Alexandria was a city where slavery thrived, but the Union’s occupation transformed it into a haven for escaped slaves, known as “contrabands.” The city became a focal point for African American freedom and military service. The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 allowed African Americans to join the Union Army, and the establishment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) followed. Over 180,000 African American soldiers, including many who had escaped bondage, served in the Union Army, determined to preserve the Union and ensure the freedom of their people.

At the heart of the story is the petition signed by 443 African American soldiers at L’Ouverture Hospital, demanding equal burial rights. This movement was sparked by the death of Private Shadrach Murphy in December 1864, who was initially buried in the segregated Freedmen’s Cemetery. Their protest led to the reinterment of 118 USCT soldiers, including Private Murphy, in Alexandria National Cemetery.

To learn more about the history and contributions of the United States Colored Troops and their connection to the Alexandria National Cemetery, visit our detailed blog post here: The Legacy of the USCT at Alexandria National Cemetery.

Private Shadrach Murphy: The Catalyst for Change

The story of Private Shadrach Murphy, a soldier from the 23rd United States Colored Infantry (USCT), illustrates not only the bravery of African American soldiers during the Civil War but also their fight for equal recognition. When Murphy died on December 25, 1864, he was initially buried in the segregated Freedmen’s Cemetery, a place reserved for African Americans, including civilians. His burial sparked outrage among his comrades, who saw this as an injustice.

Just two days after his death, 443 soldiers, many of whom were recovering at Alexandria’s L’Ouverture Hospital, signed a petition demanding that their fallen brothers be granted equal burial rights in the Soldiers’ Cemetery (now Alexandria National Cemetery). Their words resonated powerfully: “We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army… should share the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who only differ from us in color.” This act of unity and protest is regarded as one of the earliest organized civil rights actions in American history.

The petition’s success resulted in the reinterment of Private Shadrach Murphy and 117 other African American soldiers into Alexandria National Cemetery in January 1865. Murphy’s gravestone, located in Section B, Site 3330, stands as a lasting tribute to his life and the collective efforts of the United States Colored Troops to ensure dignity and equality in death as well as in life.

A copy of this historic petition is now viewable at Alexandria’s Freedom House Museum at 1315 Duke Street, offering visitors a chance to see this important document firsthand.

Private John Cooley: First Buried, Last Reinterred

Private John Cooley, a member of the 27th U.S. Colored Infantry from Ohio, was the first United States Colored Troop to be buried in the Freedmen’s Cemetery. He passed away on May 4, 1864, at Alexandria’s L’Ouverture Hospital. His funeral, noted in the diary of Quaker teacher Julia Wilbur, was a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by African American soldiers. Wilbur recorded how he was laid to rest with a white escort, reflecting the segregated treatment of the time, despite Cooley’s service to the Union Army.

Between 4 & 5 P.M. went to the funeral of a Colored Soldier the first one who has died here. Had a white escort & was buried in the New Freedman’s B. Ground. Mr. Gladwin officiated.

Miller, 1998, p. 8

Cooley’s journey did not end with his burial in the Freedmen’s Cemetery. After the successful petition led by Private Shadrach Murphy’s comrades, Cooley became one of the 118 African American soldiers to be reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery in January 1865. Remarkably, he was the last of these men to be moved, symbolizing the slow but steady progress toward equal recognition of the United States Colored Troops.

Cooley’s gravestone, found in Section B, stands as a testament to the fight for equality that extended from the battlefield to the final resting place. His story, like Murphy’s, reflects the courage of African American soldiers who not only fought in the Civil War but also battled for their rightful place in history.

The Battle of the Crater: A Turning Point for the United States Colored Troops

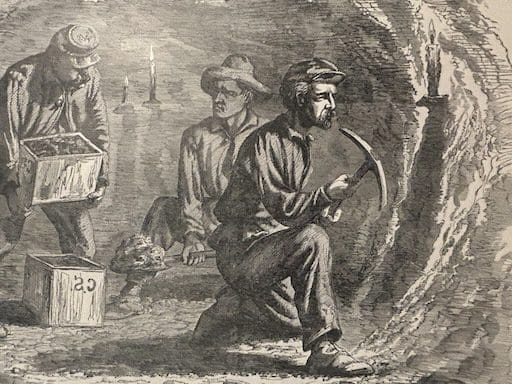

The Battle of the Crater, fought on July 30, 1864, during the Petersburg Campaign, was one of the most dramatic and tragic events of the American Civil War. Union forces, under General Ambrose Burnside, devised a plan to break through Confederate lines by tunneling beneath their defenses and planting explosives. This daring strategy aimed to create a massive crater, through which Union troops could charge and seize Petersburg, a key Confederate stronghold.

On the morning of July 30, Union soldiers from the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry detonated 8,000 pounds of gunpowder beneath the Confederate defenses, creating a crater 30 feet deep and 200 feet long. However, the well-planned explosion quickly turned into a disaster.

General Burnside had originally planned for the USCT regiments to lead the charge. These soldiers had been trained specifically to maneuver around the crater and exploit the breach. However, at the last moment, Burnside’s superiors replaced the USCT with less experienced white troops, fearing backlash over sending African American soldiers into what was considered a high-risk operation. The untrained troops charged directly into the crater, rather than around it, creating chaos as they became trapped in the deep pit. Confederate forces quickly regrouped and unleashed devastating fire upon the trapped Union soldiers, turning the crater into a death trap.

The Role of the United States Colored Troops

Amidst the chaos, the USCT regiments were eventually called into action. Soldiers from the 28th and 29th USCT entered the fray, charging bravely into the crater and engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat with Confederate soldiers. Despite their courage and determination, the battle was already lost. Confederate reinforcements poured in, and many USCT soldiers were killed, captured, or subjected to brutal treatment at the hands of Confederate troops, who held deep racial animosity toward African American soldiers.

The USCT’s involvement in the Battle of the Crater was both a tragic and defining moment. Although the battle itself was a failure for the Union, the bravery of the USCT soldiers was undeniable. Their willingness to charge into overwhelming odds highlighted their dedication not only to the Union cause but also to the fight for freedom and equality.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The Battle of the Crater was a Union failure, but it left a lasting impact on the perception of African American soldiers. The courage displayed by the USCT, even in the face of overwhelming adversity, helped to challenge the deeply ingrained racial prejudices of the time. Their bravery at Petersburg, and in battles across the war, contributed to the eventual acceptance of African Americans in the Union Army as equals in combat. Many USCT soldiers injured at the Crater were treated at L’Ouverture Hospital in Alexandria.

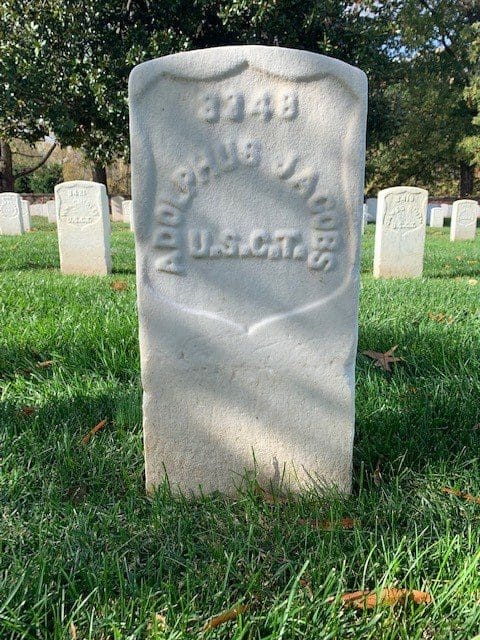

Private Adolphus Jacobs: A Tale of Courage from the Battle of the Crater

Private Adolphus Jacobs of the 28th USCT was wounded during the Battle of the Crater but continued to fight with remarkable bravery. While recovering at L’Ouverture Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, Jacobs wrote to his family about his injuries, demonstrating the resilience and determination that defined the United States Colored Troops. His letter serves as a testament to the unwavering spirit of the soldiers who fought for both the Union and their own freedom.

I never got over the hurt I received at the Charge at Petersburg, but I am as well as far as health is concerned as I ever was.”

(Miller, Edward A. Jr., Alexandria Historical Quarterly, Volunteers for Freedom: Black Soldiers in the Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II, The Office of History Alexandria, Winter 1998, Pg 2).

Sadly, Jacobs did not recover from his wounds and passed away on August 14, 1864. His story, like those of many others who fought at the Crater, is a testament to the bravery of the USCT soldiers.

For more details, see our blog: [The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery: A Historic Burial Ground for Freedmen and Fugitive Slaves in Alexandria, VA].

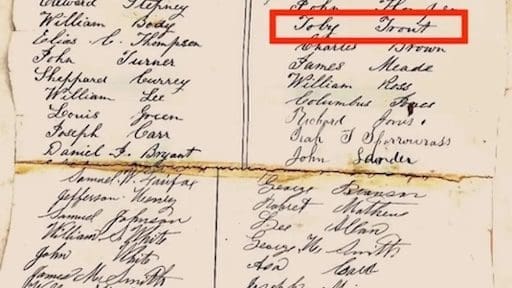

Tobias Trout: A Hero’s Journey from the Crater to the Petition

Tobias Trout, a fifer from the 31st USCT, also fought valiantly at the Battle of the Crater. Despite the chaos that ensued after Union troops mistakenly charged into the crater, Trout and his comrades showed remarkable courage, engaging in hand-to-hand combat. However, Confederate reinforcements overwhelmed the Union forces, resulting in heavy losses for the USCT.

Though wounded, Trout survived the battle and later played his fife during solemn ceremonies, honoring his fallen comrades. His dedication to justice continued when, in December 1864, he was arrested for refusing to bury Private Shadrach Murphy in the Freedmen’s Cemetery. This act of defiance sparked the L’Ouverture Hospital Petition, signed by 443 USCT soldiers, demanding equal burial rights.

This image highlights Tobias Trout’s name on a portion of the USCT petition. Sourced from the City of Alexandria’s website: The USCT and Alexandria National Cemetery.

Trout’s journey came to an end on April 15, 1865—the same day as President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination—when he succumbed to “Gangrene of the Lungs.” He is buried in Alexandria National Cemetery, Section B, Site 3478.

Tobias Trout’s journey embodies the indomitable spirit of the USCT soldiers, whose courage and resilience paved the way for a brighter future amidst the shadows of adversity and strife.

Remembering USCT Heroes: Tales of Courage Beyond the Crater

Alfred Whiting: Captured but Unbowed

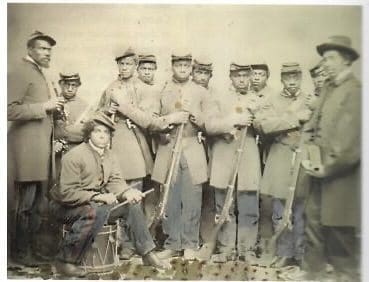

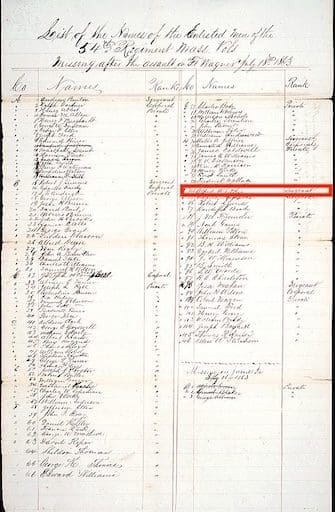

The Legendary 54th Massachusetts

Alfred Whiting served in Company I of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, an African American unit formed by Massachusetts following President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Unlike units later organized under the United States Colored Troops designation, the 54th was among the initial Black regiments to engage in the Civil War. Commanded by Robert Gould Shaw, a veteran of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry with a background in abolitionism, the regiment prepared for battle at Camp Meigs in Readville near Boston.

Alfred Whiting’s Service and Sacrifice

Training took place at Camp Meigs in Readville, near Boston, until late May 1863. On May 28, the regiment left for the front, moving through Boston amid widespread public support and boarding the DeMolay for the South. This marked a significant start to their combat service.

Before dedicating his life to the fight for freedom and equality, Alfred Whiting had already established roots and started a family. Before joining the army, Whiting was a waiter in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and married Catherine Keith in 1862, but they had no children. The 54th’s bold attack on Battery Wagner in South Carolina in July 1863 was pivotal, encouraging over 180,000 Black soldiers to join the Union Army, significantly impacting the war’s direction and the struggle for equality.

Whiting enlisted at twenty-three in Readville on April 22, 1863, becoming a sergeant in the 54th. He was missing after the July 18, 1863, Battery Wagner assault and officially listed as such in August. Despite records, Whiting was captured, enduring imprisonment in various locations.

After months of captivity, Whiting was finally exchanged in Goldsboro, North Carolina, on March 4, 1865. According to a statement in his widow’s pension file by a comrade captured with him, Whiting was first incarcerated in Charleston, then the stockade at Florence, and lastly at Goldsboro, North Carolina. He was paroled at N.E. Ferry, North Carolina, on March 4, 1865, and then forwarded to Camp Parole, Annapolis, Maryland, where he was furloughed until March 19. Whiting returned to the army but tragically succumbed to typhoid fever at L’Ouverture U.S. Hospital on June 25, 1865. He was laid to rest in section B:3519.

Alfred Whiting’s unwavering courage and ultimate sacrifice, along with that of his fellow soldiers in the 54th Massachusetts, helped pave the way for greater equality and recognition of African American contributions to the United States. Their bravery and dedication to the cause of freedom left an indelible mark on American history, inspiring future generations to continue the fight for justice and equality.

Catherine Whiting: A Widow’s Struggle for Recognition

Catherine Whiting applied for and was granted a widow’s pension on September 3, 1867, in recognition of her husband’s service and sacrifice.

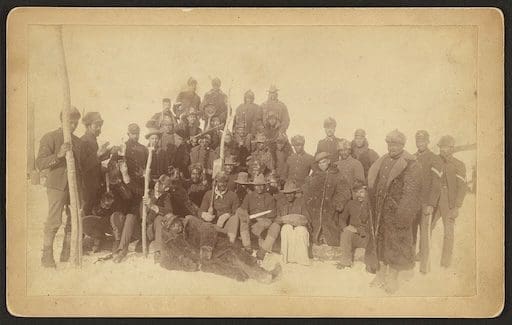

Buffalo Soldiers: Carrying on the USCT Legacy

After the war, the pioneering units of the United States Colored Troops were largely disbanded as the Army downsized dramatically. However, their legacy and impact lived on through the newly formed all-Black regimental units known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” Stationed primarily in the Western frontier, the 9th and 10th Cavalries and the 24th and 25th Infantries continued the fight for equality through their courageous service. These African-American troops also served as some of the country’s first national park rangers, playing a vital role in battles during westward expansion and against Native American tribes. Their storied nickname stemmed from comparisons to buffaloes’ fierce combat abilities and hair styling. Well into the 20th century, the Buffalo Soldiers carried on the proud legacy of African-American military service.

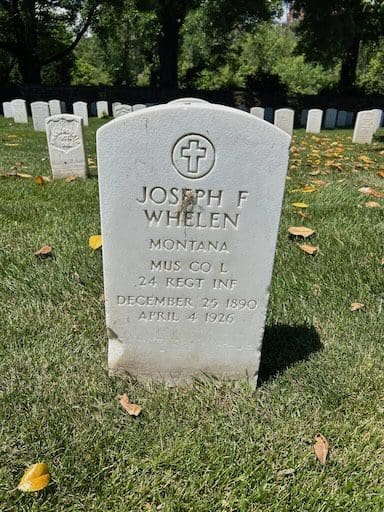

Honoring the Buffalo Soldiers at Alexandria National Cemetery

Six Buffalo Soldiers are laid to rest at Alexandria National Cemetery: Joseph F. Whelen (B:3606) from Company L of the 24th Infantry, John T. Stevenson (B:3592) from Companies A and C of the 10th Cavalry, Conny Gray (B:3587) from Company H of the 25th Infantry,

Corporal Lorenzo Foster (B:3581) from Company C of the 10th Cavalry, George Foster (B:3565) from Company C of the 10th Cavalry, and Lewis J. Cook (B:3560) from Company H of the 9th Cavalry.

For more information on the USCT members buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery and further insights into their contributions to the Union’s efforts in the American Civil War, please refer to the “Sources of Information” section at the end of this piece.

Conclusion

A Testament to Sacrifice and Resilience

The Alexandria National Cemetery stands as a testament to the sacrifices made by the brave men and women who have served our country throughout its history. From its establishment during the Civil War to the present day, this hallowed ground has been a place of remembrance, reflection, and healing for generations of Americans.

Through the stories of the soldiers and civilians laid to rest here, we gain a deeper understanding of the human cost of war and the unwavering commitment to the ideals of freedom, equality, and justice. The evolution of the cemetery’s gravestones, from simple wooden markers to enduring stone memorials, reflects the nation’s ongoing dedication to honoring those who have made the ultimate sacrifice.

The Alexandria National Cemetery is more than just a burial ground; it is a living reminder of our shared history and the unbreakable bonds that unite us as Americans. The stories of the United States Colored Troops, the Buffalo Soldiers, and the countless other heroes interred here inspire us to strive for a more perfect union and to continue the work of building a nation that truly lives up to its highest ideals.

Inspiring Future Generations

In the end, the Alexandria National Cemetery stands as a profound testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring legacy of those who have served and sacrificed for our country. May we always remember and honor their contributions, and may this hallowed ground continue to inspire and unite us for generations to come.

Photo credit: Michelle Bartels – @soussiaphotography

Sources of Information

54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. (n.d.). Roster. 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. http://54th-mass.org/about/roster/

Adjutant General, Vermont. (1892). Peck, T. S. (Ed.). Revised roster of Vermont volunteers and lists of Vermonters who served in the Army and Navy of the United States during the war of the rebellion, 1861-66. Montpelier, VT: Press of the Watchman Publishing Co.

American Battlefield Trust. (n.d.). Road to Freedom: The African American Experience in Civil War-Era Virginia (Brochure). American Battlefield Trust.

Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1897. (1898). Registers of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Artillery in the War of the Rebellion. Transmitted to the Legislature January 14, 1898. Wynkoop Allen Beck Crawford Co. State Printers. New York and Albany.

Arlington Public Schools. (2019). Camp Casey Final Report. Retrieved from https://www.apsva.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/190501_CampCasey_FinalReport.pdf

Bently, E. (1864, May 24). Letter to Captain Lee objecting to the proposal to discontinue burials at Alexandria National Cemetery. Local History / Special Collections, Kate Waller Barrett Library, Alexandria, VA.

City of Alexandria. (N.D.) USCT members buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery. Retrieved from https://www.alexandriava.gov/cultural-history/the-usct-and-alexandria-national-cemetery

Civil War Washington. (n.d.). Hospitals. Civil War Washington. Retrieved from https://civilwardc.org/introductions/other/hospitals.php

City of Alexandria. (n.d.). The USCT and Alexandria National Cemetery. Retrieved from https://www.alexandriava.gov/cultural-history/the-usct-and-alexandria-national-cemetery

Crowninshield, B. W. (1891). A history of the First Regiment of Massachusetts Cavalry Volunteers. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. The Cambridge Press.

Davis, A. (Ed.). (2023). Alexandria at War 1861-1865. African American Emancipation in an Occupied City. Office of Historic Alexandria, Press.

Freedmen’s Cemetery Memorial. (n.d.). Freedmen’s Cemetery Memorial. Retrieved from http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/index.shtml

Heiby, D. (2022). “Oh, give us a flag, all free without a slave”: Insights into the valor and contributions of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) to the Union’s efforts in the American Civil War. Civil War Insights. Retrieved from https://gravestonestories.com/oh-give-us-a-flag-all-free-without-a-slave/

Lee, J.G.C. (1864, March 29). Letter requesting authorization to purchase additional land for Alexandria National Cemetery. Local History / Special Collections, Kate Waller Barrett Library, Alexandria, VA.

Leslie, F. (1895). The American Soldier in the Civil War: A Pictorial History of the Campaigns and Conflicts of the War Between the States, Profusely Illustrated with Battle Scenes, Naval Engagements, and Portraits, From Sketches By Forbes, Taylor, Waud, Hillen, Becker, Lovie, Schell, Crane, Davis, and Other Celebrated War Artists. Stanley-Bradley Publishing Co.

McDonnell, M. (2012). The history of Little River Turnpike. Annandale Chamber of Commerce. Written for the ENDEAVOR News Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.annandalechamber.com/thehistoryoflittleriverturnpike.rhtml

Meigs, M. C. (1865, January 22). Report to Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War. Local History / Special Collections, Kate Waller Barrett Library, Alexandria, VA.

Miller, E. A., Jr. (1998). Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in the Alexandria National Cemetery, Part 1. Historic Alexandria Quarterly. Office of Historic Alexandria. Retrieved from https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/haq/historicalexandriaquarterly1998fall.pdf?_gl=1*pseacf*_ga*MTU5NTk0NjU3MC4xNzA3MDU2NzQ4*_ga_249CRKJTTH*MTcwNzA2NDY0Ny4yLjAuMTcwNzA2NDY0Ny4wLjAuMA.

Miller, E. A., Jr. (1998). Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in the Alexandria National Cemetery, Part 2. Historic Alexandria Quarterly. Office of Historic Alexandria. Retrieved from https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/haq/historicalexandriaquarterly1998winter.pdf?_gl=1*19caxxy*_ga*MTU5NTk0NjU3MC4xNzA3MDU2NzQ4*_ga_249CRKJTTH*MTcwNzA2NDY0Ny4yLjAuMTcwNzA2NTA3OS4wLjAuMA

Official website of the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery Regiment. (n.d.). News clippings mentioning Fort Lyon. Retrieved from https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/artillery/2nd-heavy-artillery-regiment/2nd-new-york-heavy-artillery-regiments-civil-war-newspaper-clippings

Olcott, M., & Lear, D. (1981). The Civil War Letters of Lewis Bissell. Field School Educational Foundation Press. Washington, D.C..

Pippenger, W. E. (2014). Tombstone inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia (Vol. 5). Heritage Books.

Rhea, G. C. (2004). The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5–6, 1864. Louisiana State University Press.

Spencer Research Library. (n.d.). Charles Joyce. The Vault. Retrieved from https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/tag/charles-joyce/

State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Retrieved from https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-1/76th-infantry-regiment

Wilson, R. (2018, June 26). Trial by fire for the U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown, Part 1. Retrieved from https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/06/26/trial-by-fire-for-the-us-sharpshooters-at-yorktown-part-1/

Wilson, R. (2018, June 26). Trial by fire for the U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown, Part II. Retrieved from https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/06/27/trial-by-fire-for-the-us-sharpshooters-at-yorktown-part-2/

All photos, except those with specific attribution, are by David Heiby and cannot be used without permission.

- The oldest national cemetery is at the Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home in NW Washington, DC, established after the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). The Annapolis National Cemetery, established shortly after the Alexandria National Cemetery, is considered the second cemetery under the July 17, 1862 Act. ↩︎