Introduction to Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

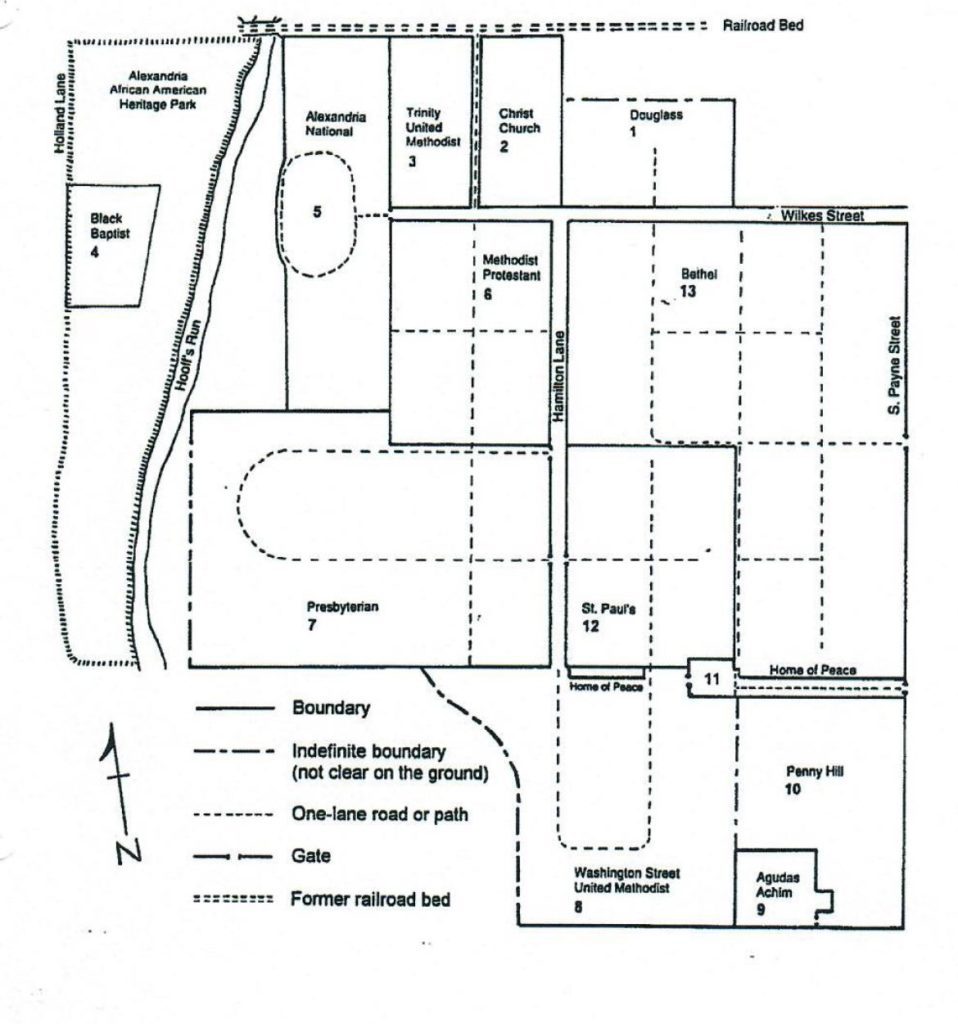

Nestled in the heart of Alexandria, Virginia, the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is a testament to the city’s rich history and cultural heritage. This sprawling burial ground, spanning nearly 82 acres, encompasses 13 historic cemeteries and is the final resting place for over 35,000 individuals.

Origins and Development

The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1803

The complex’s origins can be traced back to the early 19th century when Alexandria grappled with the terrifying prospect of disease spreading through contaminated groundwater. The devastating Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1803 brought the dire situation to the forefront, which claimed numerous lives and overwhelmed the city. In August 1803, Alexandria, then part of the District of Columbia, was ravaged by the epidemic, causing over half of the city’s 6,000 residents to flee in the face of the outbreak’s magnitude.

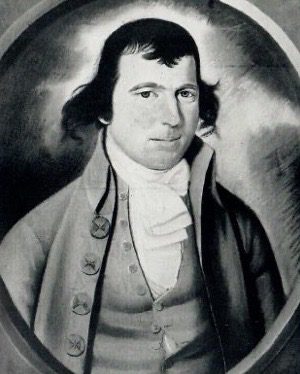

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick’s Role

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick, a prominent physician in Alexandria, played a significant role during this critical time. He attributed the epidemic’s cause to a massive pile of decaying oyster shells near the waterfront, which emitted an unbearable stench. The fear was that decomposing bodies in the city’s cemeteries would leach their bodily fluids, known today as necro leachate or necro slurry, into the groundwater and spread the disease through contaminated wells. You can read more about Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick at this [link].

City Edicts and Burial Restrictions

Alexandria’s city officials took decisive action in response to the mounting crisis caused by the Yellow Fever Epidemic and the concerns about groundwater contamination. In March 1804, they issued an edict preventing the sale of any new burial plots within the town, restricting burials to those plots that had been previously purchased or allocated.

No burying ground shall be opened, or allotted for the interment of human bodies within the limits of the corporation. Any person who shall dig a grave, or cause it to be done with a view of burying a body therein in any ground within the corporation, not opened or allotted before the twenty-seventh day of March, eighteen hundred and four for that purpose, shall forfeit and pay twenty dollars for each offense, and moreover be compelled to move the corpse, if discovered within three days after interment, under the penalty of twenty dollars for neglect.

— Ordinance of the Corporation of Alexandria, quoted in Wesley E. Pippenger, Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia (Vol. 3, p. 6).

However, as fears of disease persisted, burial practices within Alexandria grew even more restrictive. By April 1809, Christ Church Episcopal’s vestry resolved to close its churchyard to future interments, noting that “further burials in its churchyard would cease after the first day of May, next.” (Wesley E. Pippenger, Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia, Vol. 3, p. 5). Although the exact mechanism remains uncertain—whether by congregational choice or administrative pressure—it is clear that multiple denominations ceased in-town burials after May 1809. Collectively, these actions brought in-town burials to an end by mid-1809, forcing all future interments into newly established cemeteries outside the corporate limits.

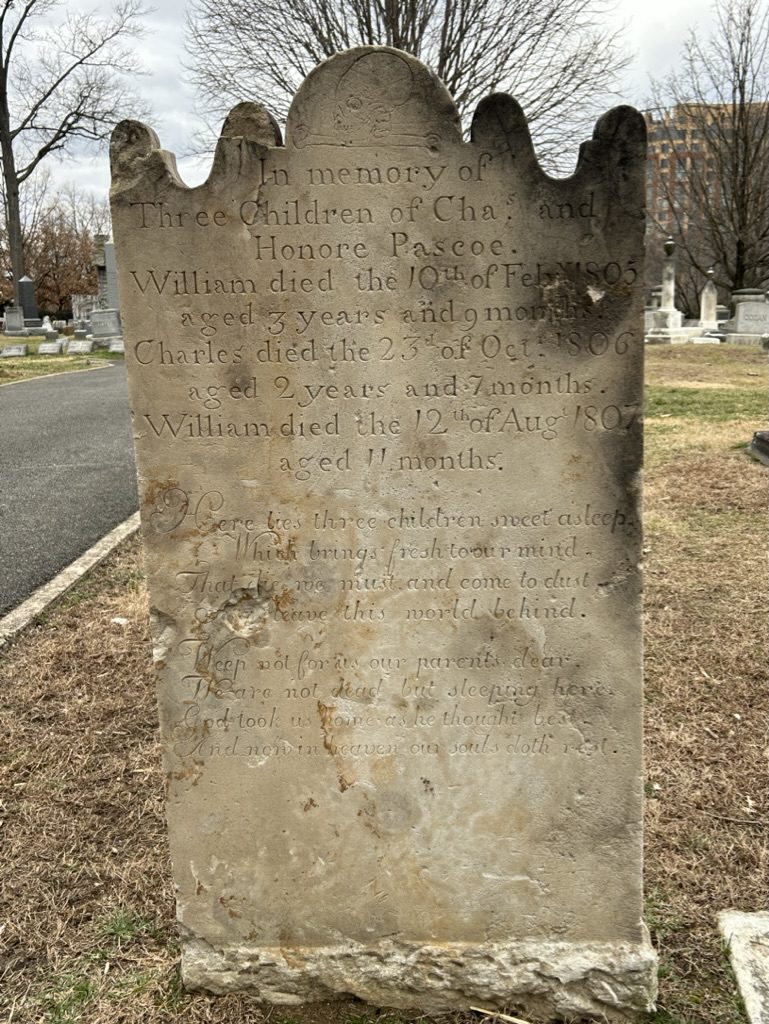

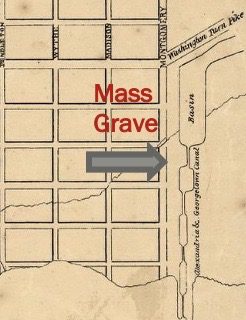

The Human Toll and Mass Graves

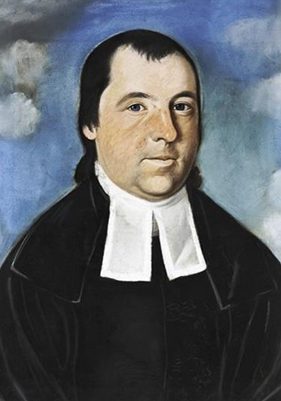

The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1803 devastated Alexandria. Reverend James Muir, pastor of the Presbyterian Meeting House and chaplain of Masonic Lodge No. 22, recorded the staggering toll in his Appendix to Death Abolished: A Sermon(1803). Between August 20 and November 1, he estimated that at least 175 Alexandrians were buried—far more than the city’s cemeteries could handle.

The Meeting House’s longtime pastor, Reverend James Muir (1757–1820), played a central role in Alexandria’s civic and spiritual life. He officiated at George Washington’s burial in 1799, offered prayers at the cornerstone ceremonies for the District of Columbia in 1791 and the U.S. Capitol in 1793, and stood at the forefront of Alexandria’s surrender to British Admiral Cockburn during the War of 1812.

When he died in 1820, the Town Council granted special permission for him to be buried within the city limits—an exception to the 1804 ordinance forbidding new in-town burials. His grave lies beneath the north floorboards of the Presbyterian Meeting House at 321 South Fairfax Street, linking the congregation’s 18th-century churchyard with its newer Wilkes Street grounds.

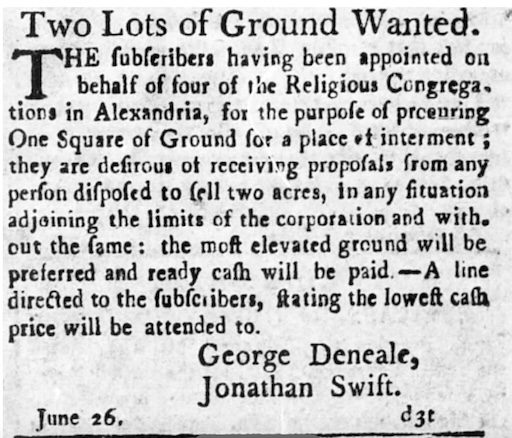

Establishment of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

Faced with these challenging circumstances, city officials and religious leaders sought to establish new burial grounds outside the crowded and unsanitary conditions of the residential areas. The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex emerged as a solution. Alexandria’s four religious congregations tasked George Deneale, senior warden at Christ Church, and Jonathan Swift to procure a suitable burial site.

Interestingly, the Spring Garden Farm had been surveyed by George Gilpin, the Fairfax County surveyor, in 1796. Gilpin had designated 128 lots on the farm for a new housing community. However, this planned community eventually went bankrupt, making the land available to establish the cemeteries.

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex emerged as a solution to the burial crisis, with the first cemeteries established on the Spring Garden Farm in the early 1800s. The complex takes its name from Wilkes Street, which was established in 1796 and named after John Wilkes, a British radical politician and journalist known for his support of the American colonies (to read more about John Wilkes, please click [here].)

The first cemeteries of the complex were established in the early 1800s on Spring Garden Farm, strategically located south of Duke Street, north of Hunting Creek, and east of Hooff’s Run. This location ensured that the new burial grounds were sufficiently distant from the city’s wells and residential areas, mitigating the risk of groundwater contamination.

Notable Cemeteries Within the Complex

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is home to thirteen historic burial grounds, each reflecting Alexandria’s diverse religious, cultural, and social history. The cemeteries below are presented in the order of their establishment, beginning in 1796 with Penny Hill and continuing through Agudas Achim in 1933. Together, they illustrate more than a century of evolving burial traditions and the stories of those who shaped the city and the nation.

Penny Hill Cemetery (1796)

Established in 1796 as Alexandria’s public burial ground, Penny Hill became the resting place of over 1,800 individuals—many in unmarked graves—including victims of the 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic, formerly enslaved people, and Civil War “contrabands.” Though little remains today, it endures as a site of both tragedy and memory, marked by the lynching burials of Joseph McCoy (1897) and Benjamin Thomas (1899). Read more →

Trinity Cemetery (1808)

Established by Alexandria’s Methodist Episcopal congregation, Trinity holds more than 550 burials, including Revolutionary and War of 1812 veterans, civic leaders, and the publisher of the Alexandria Gazette.

Christ Church Cemetery (1808)

Founded as the burial ground of Alexandria’s Episcopal parish, Christ Church holds more than 1,200 graves, including Revolutionary War veteran and Washington pallbearer George Gilpin, Boston Tea Party rebel Major Samuel Cooper, the Confederacy’s highest-ranking general Samuel Cooper, and members of the prominent Lee and Mason families.

St. Paul’s Cemetery (1809)

Established after Alexandria ended in-town burials, St. Paul’s is the final resting place of more than 1,500 individuals, from War of 1812 officers and Civil War generals to prominent local families and the city’s most enduring mystery, the Female Stranger. Recognized on the National Register of Historic Places (DHR #100-0143), it remains a landmark of Alexandria’s cultural and religious history. Read the full history of St. Paul’s Cemetery and those buried here →

Presbyterian Cemetery (1809)

Established in response to Alexandria’s Yellow Fever epidemic and 1809 burial ban, this 7.7-acre cemetery holds more than 2,400 individuals, including Revolutionary War heroes, Civil War figures, and Cold War spy William Weisband. Its 1903 wrought iron gate and Champion Star Magnolia make it one of the most evocative landscapes in the complex. Explore more →

Methodist Protestant Cemetery (1833)

Established in 1833 by Alexandria’s Methodist Protestant congregation, this cemetery holds about 1,500 interments, including slave dealer Joseph Bruin of the Duke Street jail, master silversmith and Confederate officer Major George Duffey, culinary artisan Samuel Hilton, and Confederate supporter Caroline Matilde Johnson. It is also the resting place of volunteer firefighters who perished in the tragic 1855 Dowell China Shop fire. The grounds contain a rare surviving 19th-century receiving vault and gravestones marked with fraternal symbols that reflect the civic and cultural life of 19th-century Alexandria. Read more →

Home of Peace Cemetery (1860)

Founded by the Hebrew Benevolent Society, Home of Peace is Virginia’s oldest Jewish cemetery and reflects the deep civic and commercial contributions of Alexandria’s German-Jewish community. Maintained by Beth El Hebrew Congregation, it holds leaders such as mayors Henry Strauss and Leroy Bendheim, civic figures Charles and Leopold Bendheim, philanthropist Joseph Kaufman, merchant Isaac Schwarz, and historian Ruth Sinberg Baker, who helped preserve its legacy.

Union Cemetery (1860)

Established by the Methodist Episcopal Church South and dedicated in 1860 with the Mount Vernon Guards in attendance, Union Cemetery reflects Alexandria’s Methodist schism and Civil War-era tensions, with more than 3,000 burials tied to Washington Street United Methodist Church.

Alexandria National Cemetery (1862)

The first of 14 national cemeteries created during the Civil War—established two years before Arlington—Alexandria National Cemetery was uniquely ready because the city had already purchased land for Union burials. Today more than 4,200 rest here, including soldiers from Alexandria’s wartime hospitals, 249 United States Colored Troops reinterred after a landmark 1864 petition for equal rights, victims of the Fort Lyon explosion, and civilian crew from the Black Diamonddisaster. Enclosed by Seneca sandstone walls and shaded by rare champion trees, it remains one of the nation’s most evocative Civil War landscapes. Read the full history of Alexandria National Cemetery →

Bethel Cemetery (1885)

The largest cemetery in the Wilkes Street Complex with over 12,000 burials, Bethel is the resting place of prominent Alexandrians—including Rev. Fields Cook, civil rights advocate; Julius Campbell Jr., of Remember the Titans fame; and firefighting leaders like Chief George W. Petty and “boy fireman” George Washington Whalen.

Black Baptist Cemetery (1885)

Established in 1885, the Black Baptist Cemetery reflects the resilience of Alexandria’s African American community in the face of segregation, though today few markers survive.

Douglas Cemetery (1895)

Established by and for Alexandria’s African American community, Douglass Cemetery became the final resting place of nearly 2,200 people between 1895 and 1976. Named for Frederick Douglass, it reflects both resilience and struggle, with fewer than 700 markers surviving today. Ongoing preservation efforts, led by local historian Michael Johnson, continue to honor its legacy and connect descendants to this important heritage site

Agudas Achim (1933)

Retrocession and Annexation: Impact on Cemetery Boundaries

Retrocession to Virginia in 1847 and later annexations reshaped Alexandria’s boundaries, bringing the Wilkes Street cemeteries firmly into the city. Many cemeteries, like the Presbyterian, expanded during this period to meet the needs of a growing population.

Annexation

In 1915, Alexandria incorporated more than 1300 acres of land from Fairfax and Alexandria County, encompassing the cemeteries located in the Wilkes Street Complex. With the city’s expansion, the cemeteries adjusted their boundaries to cater to the increasing population. The Presbyterian Cemetery, originally established in 1809 as a modest “one square” plot, stands as a remarkable example of this expansion. Over time, it has acquired additional land and now encompasses 7.68 acres across three parcels, with about seven acres enclosed as the historic burial ground.

Boundaries and Roads

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is framed by boundaries that themselves tell the story of Alexandria’s local, regional, and national significance.

The eastern boundary of the complex is marked by South Payne Street. At the northeast corner of Wilkes and South Payne, in the yard of 1220 South Payne Street, stands Southwest Stone No. 1 (SW1) of the original District of Columbia boundary survey. Authorized by the Residence Act of July 16, 1790, as amended March 3, 1791, President George Washington selected the site for the national capital to include Old Town Alexandria, then one of the busiest ports in America. Acting under the direction of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, surveyor Major Andrew Ellicott began laying out the ten-mile square in February 1791. On April 15 of that year, the Alexandria Masonic Lodge placed a ceremonial stone at the south corner at Jones Point, an event reported nationwide as the symbolic beginning of the federal city. The smaller marker at Jones Point was replaced in 1794 by the current engraved boundary stone. SW1, located at the cemetery complex’s corner, is therefore the oldest surviving federal monument in the United States, linking the burial grounds directly to the founding of Washington, D.C.

The northern boundary runs westward from Christ Church Cemetery along Jamison Avenue, crossing Hooff’s Run to the corner of Jamison and Holland. This line follows the bed of the former Orange & Alexandria Railroad, whose eastern terminus lay just north and east of the complex. Built in the 1850s, the railroad became one of the most strategically contested rail lines of the Civil War, extensively photographed and written about in wartime accounts. Its massive repair yard and roundhouse—destroyed by fire in the 1970s—once stood just beyond the cemetery grounds, while part of the railroad’s maintenance shops overlapped with the land later used for Douglass Cemetery, a significant African American burial ground. Even today, iron fragments and spikes occasionally surface along the boundary, physical remnants of the railroad’s presence. At the northwest corner of the complex, the 1857 stone railroad bridge over Hooff’s Run still carries traffic and has been recognized on the National Register of Historic Places since 2003.

Hooff’s Run itself plays a defining role in the landscape. The stream separates the eastern portion of Presbyterian Cemetery’s main tract (600 Hamilton Lane) from its 580 and 700 Holland Lane parcels on the west bank. On the opposite side of the Run lies the Black Baptist Cemetery, further illustrating how natural and man-made boundaries shaped the arrangement of Alexandria’s burial grounds. In the 19th century, Hooff’s Run was also used by enslaved African Americans confined in the notorious slave pens at 1315 and 1707 Duke Street, who were marched there under guard to bathe—underscoring the site’s layered legacy of freedom and oppression.

Key Historical Figures Buried Here

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is a place of historical significance and the final resting place of many notable figures who shaped Alexandria and American history. From Revolutionary War veterans and Civil War soldiers to African American leaders and influential politicians, the complex is a treasure trove of stories waiting to be discovered, including:

- Over 40 known Revolutionary War veterans

- Union troops, including United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.)

- African American leaders like Shields Cook

- General John Mason and James Murray Mason

- Dr. Holmes Paulding, a U.S. Army surgeon

- William Wolf Weisband, a Soviet spy

- Joseph Bruin, a slaver

- The mysterious “Female Stranger”

Visiting the Cemetery Complex Today

To experience these stories firsthand, join one of our guided tours of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, offered Wednesday through Sunday and led by historian David Heiby. View the tour calendar and book here.

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex continues to serve the community today, with several active cemeteries still conducting burials. Visitors can explore the beautiful grounds, take part in expert-led tours, and attend special events celebrating the complex’s rich history.

- Hours: Sunrise to Sunset

- Parking: Available on Wilkes and Hamilton.

- Address: 1475 – 1501 Willkes Street, Alexandria, VA 22314

- Expert-led tours by Presbyterian Cemetery Superintendent David Heiby most Saturdays

- Special events like Wreaths Across America and Flag-In Day

- Opportunities for walking, exploring nature, and connecting with history

In conclusion, the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is a historical gem that showcases Alexandria’s deep roots and cultural heritage. Its 13 historic cemeteries, spanning over two centuries, offer a fascinating glimpse into the lives and legacies of the individuals who helped shape the city and the nation. By preserving and cherishing this remarkable cemetery complex, we ensure that future generations can continue to learn from and be inspired by the stories of those who came before us.

References and Further Reading

Blanton, W. B. (1931). Medicine in Virginia in the nineteenth century. Garrett & Massie.

Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia. (n.d.). Information on DC boundary stones. [Official website].

City of Alexandria. (n.d.). Information on Alexandria’s archaeology. [Official website].

City of Alexandria. (n.d.). Information on cemeteries. [Official website].

Cromwell, T. T., & Hills, T. J. (1989). The Phase III mitigation of the Bonstz Site (44AX103) and the United States Military Railroad Station (44X105) located on the south side of Duke Street (Route 236) in the City of Alexandria, Virginia. James Madison University Archeological Research Center. Project #0236-100-107, C 501. Submitted to the Virginia Department of Transportation.

Gardner, W. M., Snyder, K. A., Hurst, G., Walker, J. M., & Mullen, J. P. (1999). Excavations at the Old Town Village site, corner of Duke and Henry Streets, Alexandria, Virginia: An historical and archeological trek through the 200-year history of the original Spring Garden development. Report prepared for Eakin and Younentob.

Greenly, M. (1996). Those upon the curtain has fallen: The past and present cemeteries of Alexandria, VA. Alexandria Archaeology Publications.

Hahn, T. S., & Kemp, E. L. (1992). The Alexandria Canal: Its history & preservation. West Virginia University Press for the Institute for the History of Technology & Industrial Archaeology.

Muir, J. D. D. (1803). Death abolished: A sermon, occasioned by the sickness which prevailed at Alexandria during August, September, and October, giving detail of that sickness and some of the views of Providence in such calamitous visitations. With an appendix, containing facts relating to the origin of the sickness—the extent of the mortality—the labors of the committee of health, and the contributions for the relief of the poor. Cotton and Stewart.

Munson, J. D. (Compiler). (2013). Alexandria, Virginia Alexandria Hustings Court deeds 1783–1797. Heritage Books.

Munson, J. D. (Compiler). (2015). Alexandria, Virginia Alexandria Hustings Court deeds 1797–1801. Heritage Books.

Pippenger, W. E. (1992). Tombstone inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volumes 1–5. Family Line Publications; Heritage Books.

Ricks, M. K. (2008). Escape on the Pearl: The heroic bid for freedom on the Underground Railroad. HarperCollins.

Rothman, J. D. (2021). The ledger and the chain: How domestic slave traders shaped America. Basic Books.

Van Horn, H. M. (2009). The Presbyterian Cemetery Alexandria, Virginia 1809 – 2009. The Arlington Press.

Never knew Dr. Elisha Dick was involved in the yellow fever outbreak in Alexandria.until I read this blog.Keep up the good work David