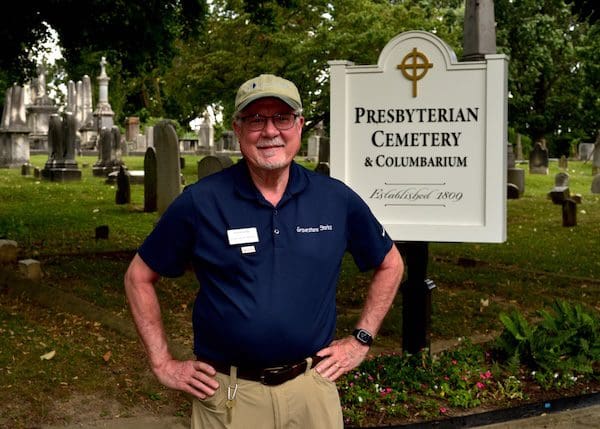

Overview

As one of the earliest Protestant burial grounds in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, the Presbyterian Cemetery encompasses 7.68 acres across three parcels and illustrates Alexandria’s transition from in-town churchyards to expansive suburban cemeteries.

Within its historic seven-acre burial ground rest more than 2,400 individuals central to the city’s civic, military, and cultural history, including Revolutionary War figures such as Capt. William Harper and Mayor Dennis Ramsay, War of 1812 naval hero John Thomas Newton, Mayor and Congressman Lewis McKenzie, Civil War veterans including Samuel R. Johnston—the Army of Northern Virginia’s reconnaissance officer whose misidentification at Gettysburg has been blamed for the Confederate defeat—and the McKnight brothers, Cold War Soviet spy William Weisband, and members of prominent local families including the Jamiesons, Muirs, Vowells, and Cazenoves.

Origins and Early Burials (1803–1809)

The cemetery’s origins lie in Alexandria’s Yellow Fever epidemic of 1803, which claimed 197 lives and overwhelmed the city’s existing churchyards. Rev. Dr. James Muir, pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Alexandria, documented the devastating outbreak in a sermon later published with an appendix detailing “the extent of the mortality” and the city’s public health response.

In the epidemic’s wake, Alexandria—then part of the District of Columbia—passed an ordinance on March 27, 1804, expressly prohibiting “the opening or allotting of any new burying ground for the interment of human bodies within the limits of the Corporation.” The act imposed fines for violations and required the removal of bodies interred after its passage, directly forcing Alexandria’s congregations to seek burial grounds outside the town’s boundaries.

By 1806, the city’s religious communities were actively coordinating their response. On June 26, 1806, George Deneale, senior warden at Christ Church, and Jonathan Swift placed an advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette seeking a suitable burial site for four congregations. This interfaith cooperation would shape the development of what became the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Early Interments at Spring Garden Farm

Evidence confirms that Presbyterians were already burying their dead at the Spring Garden Farm site well before formal acquisition. The Health Office reported six burials in the “Presbyterian” cemetery during August–September 1803, at the height of the epidemic. Physical evidence corroborates these records: a gravestone for George Kilton records both his death on October 18, 1803, and his son George’s earlier burial in November 1802—demonstrating the site was in use even before the 1804 ordinance.

Additional gravestones survive with dates as early as 1803, and one marker—Martha Bryon McKnight (d. 1775)—predates the cemetery’s establishment entirely, likely transferred from the Meeting House burial ground.

Formal Establishment

On June 22, 1809, a committee of church members—including Thomas Vowell, James Irwin, Joseph Riddle, Richard Veitch, Hugh Smith, Joseph Deane, Andrew Jamieson, Alexander McKenzie, and the late Joseph Harper—entered into a lease agreement with Philip G. Marsteller (son of Lt. Col. Philip Marsteller, d. 1803) and his wife Christiana D. J. Cooper Marsteller (1773–1815) for a “square of ground” at Spring Garden Farm.

The transaction was formalized by deed on February 6, 1813, when the “Presbyterian Congregation of the Town of Alexandria” secured full ownership for $450, recorded in Fairfax County Deed Book M2, page 311. Christiana Marsteller herself was later interred in the cemetery, likely in Section 41:29 or 42.

This deed provides one of the earliest surviving legal descriptions of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, situating the Presbyterian tract “on the south side of Gibbon Lane, north side of Franklin Lane, west side of Hamilton Lane, and east side of Mandeville Lane.”

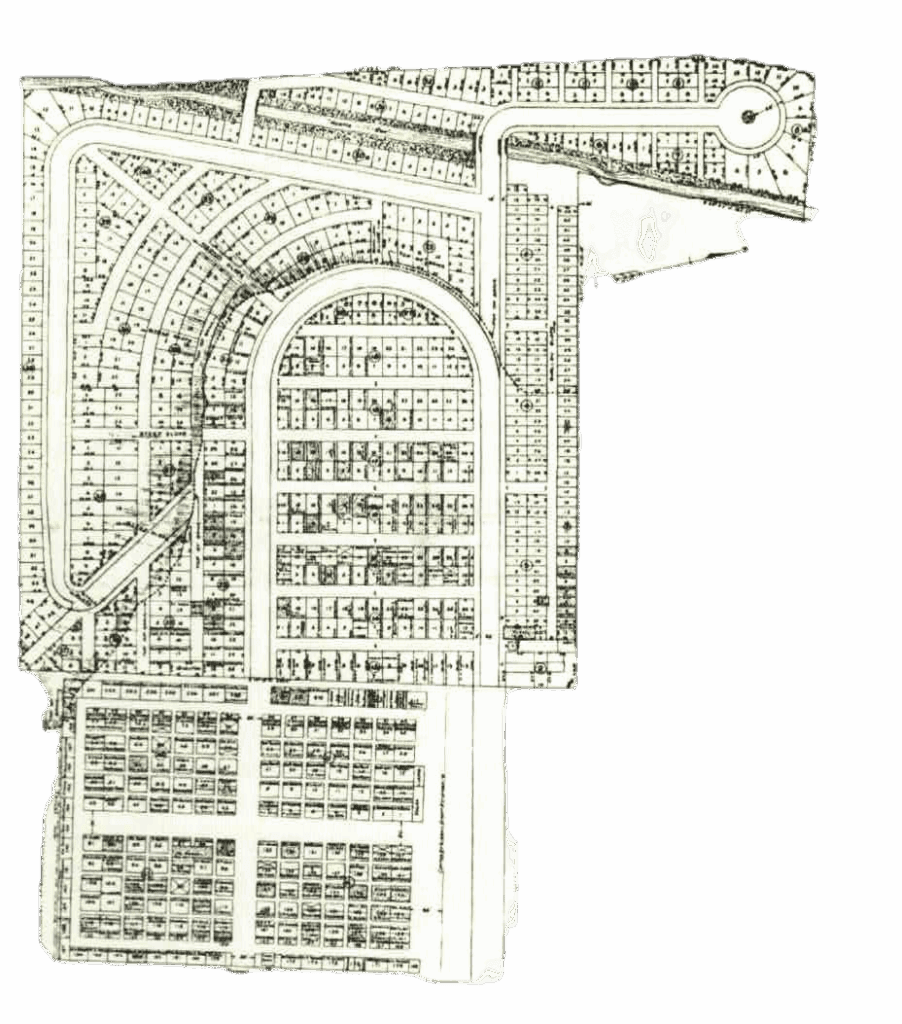

Survey Map and Boundaries

An 1890 survey map of the Presbyterian Cemetery shows burial plots extending across Hooff’s Run. The section on the upper right, across the Run, later became part of what is now the Alexandria African American Heritage Park.

Boundary Description

Today, the Presbyterian Cemetery consists of three parcels:

- 600 Hamilton Lane — 322,549 sq ft (approx. 7.40 acres). This principal parcel contains the active burial grounds, with about seven acres enclosed by fencing. Portions of this tract also extend onto the west bank of Hooff’s Run.

- 580 Holland Lane — 1,139 sq ft (approx. 0.03 acres). Located on the west bank of Hooff’s Run.

- 700 Holland Lane — 11,061 sq ft (approx. 0.25 acres). Also located on the west bank of Hooff’s Run.

The original burial tract encompassed roughly seven acres in a rectangular form. The cemetery fronts Hamilton Lane on the east. From the northeast corner, the property line extends west, separating the cemetery from the Methodist Protestant Cemetery. The westernmost portion of the northern boundary abuts Alexandria National Cemetery, with the northwest corner lying about 100 feet west of Hooff’s Run. The southern boundary runs roughly parallel to the northern line, separating the cemetery from the Washington Street United Methodist Cemetery (Union Cemetery) and, along its western section, from the property now owned by RiverRenew (Alexandria Sanitation Authority).

The cemetery’s boundaries historically extended beyond Hooff’s Run, with burial plots recorded on the west bank in an 1890 survey map. In the mid-20th century, infrastructure projects and, in 1994, a boundary agreement with Norfolk Southern Railroad and the Carlyle Development altered this portion of the property. As part of that settlement, the trustees donated land on the west side of Hooff’s Run for the creation of the Alexandria African American Heritage Park. In exchange, the cemetery received adjoining parcels, including the 580 and 700 Holland Lane tracts, ensuring continued ownership on the west bank even as part of the land became park space.

Landscape and Contributing Features

The cemetery stands out for its canopy of mature trees, including maples over 100 years old, lime lindens planted in the mid-20th century, and a massive eastern cottonwood estimated at more than 150 years old along the northern edge bordering Alexandria National Cemetery. A particularly notable specimen is the Star Magnolia (Magnolia stellata), surrounded by gravestones from the 1850s–1890s and recognized as a Notable–Champion (SC2) tree with a National Tree Registry score of 139. Despite age-related features, the magnolia remains healthy and carefully maintained in its historic setting.

The Victorian Gate and Enclosure

Only the seven-acre burial ground is enclosed by fencing. The front section, dating to 1903, features an ornate Victorian-style gate with decorative scrollwork and gold lettering, while later fencing completes the remainder of the enclosure. This historic gateway remains one of the site’s most recognizable features and underscores the cemetery’s enduring integrity of design, setting, and association within Alexandria’s layered history.

Main entrance gate of Presbyterian Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia. The black wrought iron Victorian-style gate, built in 1903, features ornate scrollwork and gold lettering reading “Presbyterian Cemetery 1809.” Trees and gravestones are visible inside the fenced grounds beyond the gate.

Closing Interpretation

These living and structural features contribute to the cemetery’s integrity of design and setting, and have themselves become landmarks in Alexandria’s cultural landscape. The Presbyterian Cemetery’s well-documented origins in Alexandria’s 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic and its role in the city’s early public health reforms contribute to the historical significance of the entire Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Today, the Presbyterian Cemetery continues to serve both as a place of remembrance and as an outdoor archive of Alexandria’s past. More than 2,400 individuals are laid to rest here—each with a story that adds depth and meaning to Alexandria’s history. From war heroes and civic leaders to merchants, ministers, and everyday citizens, their lives reflect the challenges, values, and transformations that shaped this community.

Looking for burial arrangements, visitor access, or cemetery regulations?

Visit the official site of the Presbyterian Cemetery of Alexandria →.

Discover the Lives Behind the Stones

To help you explore these personal histories, we’ve organized our growing collection of mini-biographies into three alphabetical sections:

- Part 1: Surnames A–G

- Part 2: Surnames H–N

- Part 3: Surnames O–Z

Interested in walking through history? Join us for a guided tour, where we share these stories—and many more—on the grounds where they unfolded.

Important Visitor Information

The Presbyterian Cemetery is a controlled-access cemetery. To learn more about visiting policies and procedures, please click here [Link].

To view a map of the different sections of the cemetery, click [here].

Sources of Information

Published Sources

Alexandria Common Council. (1804). An act reducing into one and amending the several acts respecting the removal of nuisances and the preservation of the health of the town. Alexandria Statute Book D, pp. 100-101.

Alexandria Health Office. (1803, September 14). List of burials in the different burial grounds of the town, since the 20th of August. Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer.

Blanton, W. B. (1931). Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century. Garrett & Massie, Inc.

Brockett, F. L., & Rock, G. W. (1883). A Concise History of the City of Alexandria, VA, from 1669 to 1883 with a Directory of Reliable Business Houses in the City. Gazette Book and Job Office.

Cox, E. (1976). Historic Alexandria, Virginia Street by Street; A Survey of Existing Early Buildings. EPM Publications.

Fleming, L. B., Rhodes, E. F., & Fleming, J. E. (1981). Centennial Thomas Fleming 1881-1941. AdArt.

Gaughan, A. J. (2011). The Last Battle of the Civil War. United States Versus Lee, 1861 – 1883. Louisiana State University Press.

Hakenson, D. C. (2011). This Forgotten Land Volume II, Biographical Sketches of Confederate Veterans Buried in Alexandria, Virginia. Donald Hakenson.

Hamilton, E. J. (2021). A Scottish Migration to Alexandria. Ellen J. Hamilton.

Lee, C. G., Jr. (1957). Lee Chronicle Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia. Thomson-Shore.

Lewellen, A. (2007, February). Discovering Torthorwald, Bridekirk, and Lymekilns through John Carlyle’s Inventory. Carlyle House Docent Dispatch. Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority. https://www.novaparks.com/sites/default/files/pdf/February07.pdf

Madison, R. L. (2005). Walking with Washington. Gateway Press, Inc.

McGroarty, W. B. (1940). The Old Presbyterian Meeting House at Alexandria, VA 1774 – 1874. The William Byrd Press, Inc.

Miller, T. M. (1987). Pen Portraits of Alexandria, Virginia, 1739-1900. Heritage Books.

Miller, T. M. (1991). Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, Virginia, 1780-1820: Volume 1. Heritage Books, Inc.

Miller, T. M., & Smith, W. F. (2001). A Seaport Saga Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia. The Downing Company Publishing.

Moore, G. M. (1949). Seaport in Virginia George Washington’s Alexandria. Garrett and Massie, Incorporated.

Muir, J. (1814). Death abolished: A sermon, occasioned by the sickness which prevailed at Alexandria during August, September, and October [1803 sermon reprinted]. Alexandria, D.C.: Samuel Snowden for Robert Gray.

Peck, G. (2015). Andrew Wales: Alexandria’s First Brewer. The Alexandria Chronicle. A publication of the Alexandria Historical Society, Spring 2015(2).

Pippenger, W. E. (1992). Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volume 1. Family Line Publications.

Province of Pennsylvania. (1992). Officers and Soldiers in the Service of the Province of Pennsylvania, 1744-1765.

Quander, R. (2021). The Quanders, Since 1684, an Enduring African American Legacy. Christian Faith Publishing, Inc.

Rainey, B. (2022). The Last Slave Ship. The True Story of How the Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning. Simon and Schuster.

The Alexandria Association. (1956). Our Town 1749-1865 at Gadsby’s Tavern Alexandria, Virginia. The Dietz Printing Company.

Van Horn, H. M. (2009). The Presbyterian Cemetery Alexandria, Virginia 1809 – 2009. The Arlington Press.

Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation. (2023). Lee-Fendall House Historic Structure Report: Final Report. SmithGroup.

Wenzel, E. T. (2015). Chronology of The Civil War in Fairfax County. Part I. Bull Run Civil War Round Table.

Unpublished Works:

Browne, S. H. (2023, October). The Davidson, Hulfish, and English Family Lots at the Presbyterian Cemetery, Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, Alexandria, Virginia. Unpublished manuscript, 45 pages, including family histories, mini-biographies, and images.

Dahmann, D. C. (2002). The Roster of Historic Congregational Members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House.

Family Papers and Manuscripts

Gibson, P. “Pete”. (n.d.). Excerpts of the Gregory Family Letters of Alexandria, Virginia, pp. 12–13, 19, and other unnumbered pages. Provided by Pete Gibson, a descendant of the Gregory family.

Pamphlets:

Old Presbyterian Meeting House’s Visitor’s Guide to Alexandria’s Historic Old Presbyterian Meeting House. (n.d). Trifold pamphlet.

Websites:

Alexandria Archaeology Office of Historic Alexandria. (2010). Alexandria, a living history: Alexandria waterfront history plan. City of Alexandria, Virginia. https://dockets.alexandriava.gov/icons/PZ/BAR/ohad/cy11/020211/waterfront.pdf

Christopher H. Jones Antiques. (n.d.). John Muir Secretary. Retrieved from https://www.christopherhjones.com/john-muir-secretary/

City of Alexandria, Virginia. (1992). Historic Preservation. In Adopted 1992 Master Plan Alexandria, Virginia. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/planning/info/masterplan/masterplan=historic=preservation=pt2.pdf

George Washington’s Mount Vernon official website. (n.d.). Ramsay’s farewell speech at Wise’s Tavern. URL: https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/ten-facts-about-washington-slavery/

Official Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park. (2022). Blog on Capt. Samuel R. Johnston. URL: https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2022/05/30/capt-samuel-r-johnston/

Official website of the Captain Cook Society. (n.d.). Cook’s Third Voyage. URL: https://www.captaincooksociety.com/home/detail/cooks-third-voyage-1776-1780

Official website of Cincinnati Whig newspaper. (2019). Article about the Moselle. URL: https://cincinnatiwhig.com/2019/01/28/thursday-january-29-1852/

Official website of the City of Alexandria, Office of Historic Alexandria. (n.d.). Alexandria Times Out of the Attic. URL: https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic/info/default.aspx?id=94188

Official website of the Friendship Firehouse Museum. (n.d.). Firehouse information. URL: https://www.friendshipfirehouse.net/

Official website of Military Images Digital. (2022). Article on Samuel Johnston. URL: https://militaryimages.atavist.com/a-northern-yankee-in-lee-s-army

Official website of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. (n.d.). Church history. URL: https://www.opmh.org/history

Official website of Steamboats.org. (2019). Article about the Moselle. URL: https://www.steamboats.org/history/potomac-river-and-the-steamboat-moselle.html

Official website of Washingtonian Magazine. (n.d.). Article about the Mysteries of the Washington Cathedral. URL: https://www.washingtonian.com/2012/07/02/the-mysteries-of-washington-national-cathedral/

Official archives website of The Washington Post. (n.d.). Dowell China Shop Fire. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1982/11/30/fire-destroys-old-alexandria-shop/fe4300a2-ebdd-4f64-96fc-943a3a913227/

Roberts, J. (2017, November 17). Mount Zephyr. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://jay.typepad.com/william_jay/2017/11/mount-zephyr.html