The Formation of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment

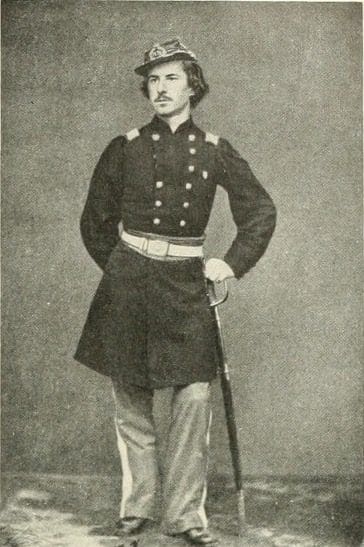

The Fire Zouaves, consisting of multiple regiments including the 11th Regiment New York Volunteer Infantry, were assembled in New York City in May 1861. This infantry regiment of the Union Army was formed as a Zouave unit and was composed of volunteers from the city’s fire companies. They were led by Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, who, despite not attending West Point, was well-versed in the Zouave technique due to his training in fencing and extensive study of French military literature. In 1859, he established the U.S. Zouave Cadets in Chicago. He conducted rigorous training sessions, including bayonet drills, firing techniques, and the “rallying by fours” tactic, which involved forming combat-ready units to counter attacks from various directions.

The Fire Zouaves Arrive in Washington, D.C., and Swearing-In Ceremony

These soldiers were notable for their unique attire and drill style, which deviated from the typical Union soldier uniform. They had two sets of uniforms during the War. The initial uniform, created by Ellsworth upon the regiment’s formation, was made of affordable fabric, but it was later replaced after falling apart.

The Fire Zouaves and the Willard Hotel Fire of 1861

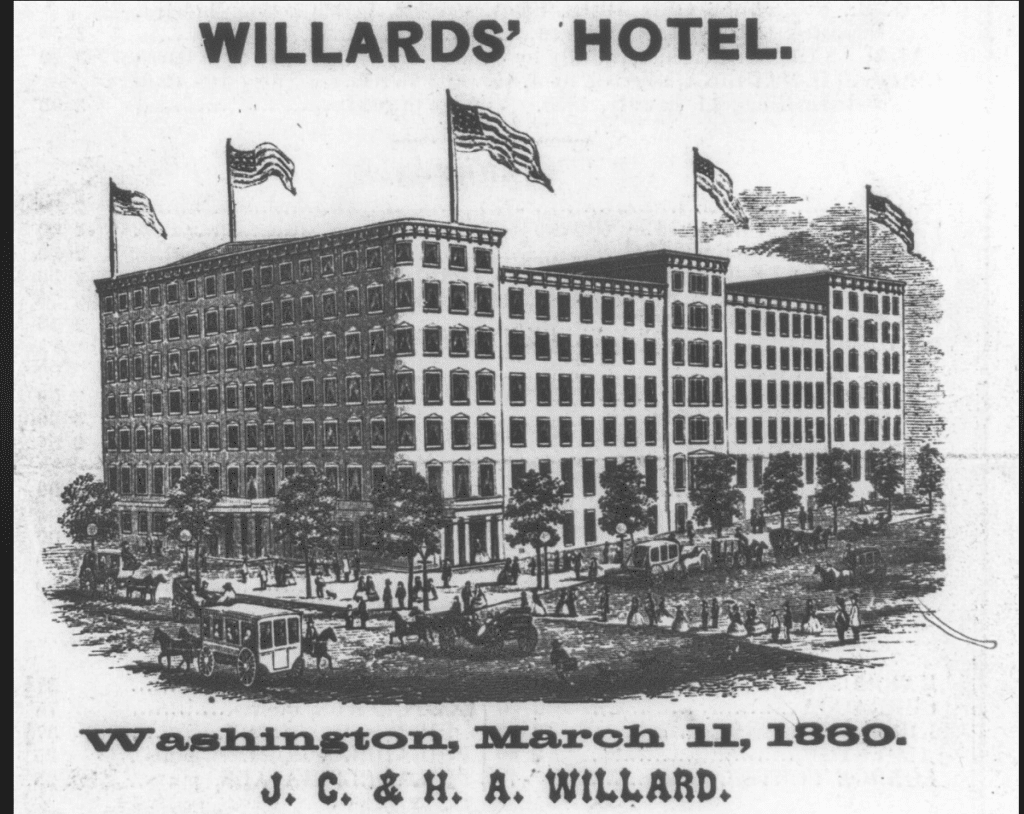

On May 2, 1861, just over 1,000 men from New York arrived in Washington, DC, and were mustered out. The 11th New York officially entered Federal service on May 7th, 1861, in a ceremony at the unfinished Capitol in the presence of President Lincoln and his son, Tad. New York, with its significant French immigrant population, contributed the largest number of Zouave units during the war. Of the 30 regiments from New York that were recruited during the conflict, four were established in April and May of 1861 as part of the initial wave of Zouave regiments. The majority of Zouave regiments were raised in eastern states such as New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, with a notable number also coming from the Midwest. By the war’s end, the North had raised over 80 Zouave regiments, while the South had around 20. Louisiana, with its strong French influence, produced the most Zouave regiments in the South. Interestingly, before engaging in battle, the 11th NY Regiment demonstrated their firefighting skills when they helped extinguish a fire at Willard’s Hotel on May 9, 1861.

The site at 1401 Pennsylvania Ave initially housed Tennison’s Hotel. It began with six small houses built in 1816 by John Tayloe III’s enslaved and leased to Tennison. Over the subsequent three decades, the hotel underwent name changes and had different leaseholders. By 1847, the buildings needed repair. Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, John’s son, sought a tenant to maintain and operate the structures for a profit. In 1847, Henry Willard leased the buildings, formally establishing the Willard Hotel. He amalgamated the six buildings into one, expanding it into a four-story hotel. In 1864, he went on to purchase the hotel.

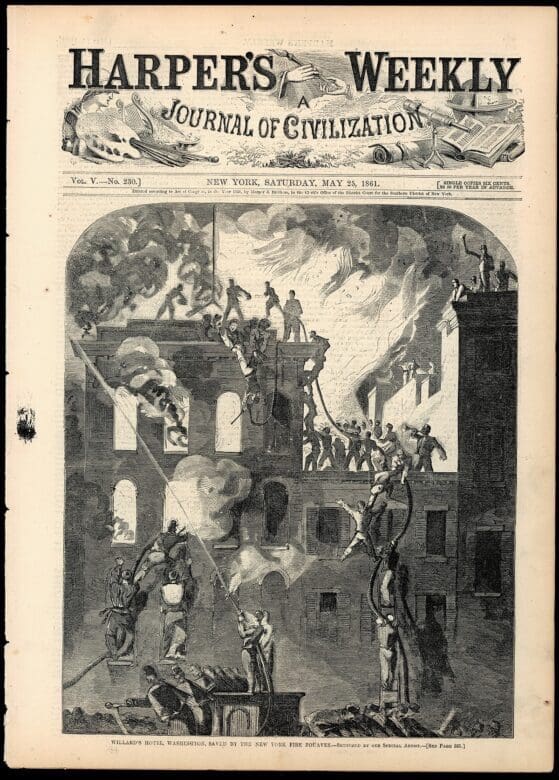

The Fire Zouaves at the Willard Hotel Fire

Colonel Ellsworth directed ten men from each company to respond to the fire, but the entire regiment arrived at the scene. There were more people present than even the Washington Fire Department. Taking charge, Colonel Ellsworth assumed command of the incident after taking the fire chief’s trumpet. Despite initial protests from a fireman, Ellsworth asserted his authority with the statement, “Well, if you have more people here than I do, you can take it.” The Zouaves, being firemen with special training, demonstrated remarkable skill in extinguishing the fire. Their bravery and expertise were evident as one of them reached down from a roof for the hose pipe, while supported by two comrades. This courageous act exemplified their exceptional abilities in handling the emergency. The fire was applied to the destroyed building in three places, and it was no doubt a deliberate attempt to burn out Willard’s hotel. The property burned comprised a news depot, drug store, saloon &c[i].,”

Recognition and Gratitude for the Fire Zouaves

After successfully extinguishing the fire, Henry Willard generously invited the regiment to breakfast and a collection of money was made, providing them with $500 to support their efforts. Following a brief congratulatory speech from Col. Ellsworth, and accepting Mr. Willard’s invitation to breakfast, they expressed their jubilation with three immense cheers, sang ‘Dixie,’ and then marched in perfect order to their quarters. The following day, they enjoyed racing with the engines on the Avenue, and their striking appearance in their red shirts evoked memories of a fire alarm in New York.

The $500 gift would later serve a somber purpose—it was used to pay for the funeral expenses of Colonel Ellsworth, who was killed in Alexandria just two weeks later.

The Fire Zouaves in Alexandria: The Death of Colonel Ellsworth

On May 24, 1861—the day after Virginia voted to secede from the Union—Federal troops crossed the Potomac and occupied Alexandria. The city would remain under Union control for the duration of the Civil War, with its homes, churches, and cemeteries transformed into military hospitals, supply depots, and encampments.

One of the most dramatic events of that morning occurred at the Marshall House Hotel, now the site of The Alexandrian Hotel at 480 King Street. Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth (1837–1861), a close friend of President Lincoln and commander of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves, removed a massive Confederate flag flying from the hotel’s rooftop—reportedly visible from the White House. As Ellsworth descended the stairs with the captured banner, he was shot and killed by the hotel’s proprietor, James W. Jackson, a staunch secessionist. In turn, Union Private Francis Brownell shot and killed Jackson on the spot.

Ellsworth’s death was widely considered the first Union casualty of the Civil War, and it electrified the North. President Lincoln, stricken with grief, personally accompanied Ellsworth’s body as it lay in state at the White House. Brownell was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.

Final Resting Places of Ellsworth and Jackson

After the tragedy at the Marshall House, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth’s body was returned to New York. He was laid to rest in Hudson View Cemetery in Saratoga County, where thousands came to pay their respects.

James W. Jackson’s burial story is more complex. Jackson was originally interred with his mother in the Jackson Family Cemetery on Swinks Mill Road, a small quarter-acre plot that had been reserved when the family sold their land in 1843. The cemetery, later surveyed multiple times in the 20th century, contains six burials and is marked by two memorial obelisks erected by descendants. According to records in the Virginia Room of the Fairfax City Regional Library, Jackson was later disinterred and reburied with his wife Susan in Section I, Lot 43 of the Fairfax City Cemetery, where he rests today.

These final resting places—Ellsworth in New York, and Jackson in Fairfax—remain enduring reminders of the sacrifices and divides of the Civil War.

Continued Service and Mustering Out

The 11th New York “Fire Zouaves” guarded Alexandria until July 1861 and fought their first major action at the First Battle of Bull Run. After heavy losses, they returned to New York to reorganize before encamping at Fort Monroe under Brig. Gen. Joseph Mansfield.

In March 1862, they witnessed the famous duel between the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia, with two men even helping fire the guns aboard the doomed USS Cumberland. Disease and dwindling numbers soon forced the regiment home, and it was mustered out on June 2, 1862.

Legacy and Sacrifice of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves

In all, the Fire Zouaves lost 66 men, including their commander Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, whose death in Alexandria inspired the cry “Remember Ellsworth!” and the formation of the 44th New York, Ellsworth’s Avengers. In 1903, the Marshall House flag Ellsworth had died seizing was returned to the War Department, a lasting symbol of their sacrifice.

Sources of Information

Janesville Daily Gazette. (1861, May 15). The New York Zouaves at a fire. Janesville, WI.

The Berkshire County Eagle. (1861, May 16). Pittsfield, MA, p. 1.

Monmouth Democrat. (1861, May 16). Freehold, NJ, p. 2.

York Gazette. (1861, May 14). York, PA, p. 2.

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). 11th New York Infantry Regiment. In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/11th_New_York_Infantry_Regiment

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Willard InterContinental Washington. In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willard_InterContinental_Washington

5th New York Volunteer Infantry, “Duryee’s Zouaves.” (n.d.). History. Retrieved September 25, 2025, from https://fifthnewyork.com/history.html

You can read more about the Fire Zouaves and their time in Alexandria (between May 25 and July 15) in my book ‘Civil War Northern Virginia 1861.’ Let’s just say they were not very welcome by the local population!

Bill,

I can vouch for your book—it’s an excellent read and full of detail. The Fire Zouaves certainly made their presence felt in Alexandria during those weeks. Between the Marshall House tragedy and their uneasy relations with townspeople, they were remembered long after their departure.

An excerpt from my book, ‘Civil War Northern Virginia 1861’: “A long time after – a year or perhaps two, I met with some Confederate scouts, Captain Kinchelow was one of them, and he told me, how those vile brutal Zouaves had behaved at our house, and at other places, how they had mal-treated and tyrannized over the citizens generally, and they had determined with one accord if it was ever in their power to make an end of them. Their conspicuous dress made them a ready mark, and he did not believe when the battle [First Manassas] was over there was one left to tell the tale.”

Bill,

What a powerful excerpt—thank you for sharing it. Delaware Kemper, who commanded the Alexandria Light Artillery at First Manassas and now rests in St. Paul’s Cemetery within the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, also left his mark on the Zouaves and their comrades. As the Union army retreated across the Cub Run Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike, Kemper’s cannonade shattered the crossing and turned the flight into what became known as “the Great Skedaddle.”