On the morning of January 18, 1827, panic spread through the streets of Alexandria, Virginia. A fire had broken out in a warehouse on Royal Street—part of the Green Furniture Factory—just as workers returned from breakfast. What began as a workplace accident quickly became a citywide catastrophe, known ever since as Alexandria’s Great Fire.

The blaze destroyed 53 buildings, including homes, warehouses, and much of the 100 block of Prince Street’s storied Captain’s Row. Flames consumed residences belonging to the Wise, Green, and Stabler families on Fairfax Street and devastated the properties of the Vowell, Fitzhugh, Fowle, and Smoot families on Prince. The loss was staggering—valued at more than $107,000 at the time—and left hundreds displaced.

Recent research confirms that among the buildings destroyed on Prince Street were 100, 101, 103, 105, 106, 108, 109, 111, 113, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 123, 127, 128, and 130 Prince Street, with 104, 110, and 125 Prince likely damaged. These addresses, many now part of the city’s most photographed block, reflect how deeply the fire scarred Alexandria’s historic landscape.

A City Responds

Despite the best efforts of Alexandria’s fire companies, the scale of the disaster overwhelmed local resources. Over 300 Navy Yard workers, including enslaved men like Michael Shiner, were dispatched from Washington to help combat the blaze. Their efforts were critical in containing further destruction. In the aftermath, Congress allocated $20,000 in relief funds, and donations poured in from across the region.

The fire marked a pivotal moment in Alexandria’s development—but it was also a turning point in the life of one man whose family would leave an indelible mark on the city.

James Green: Builder of a Legacy

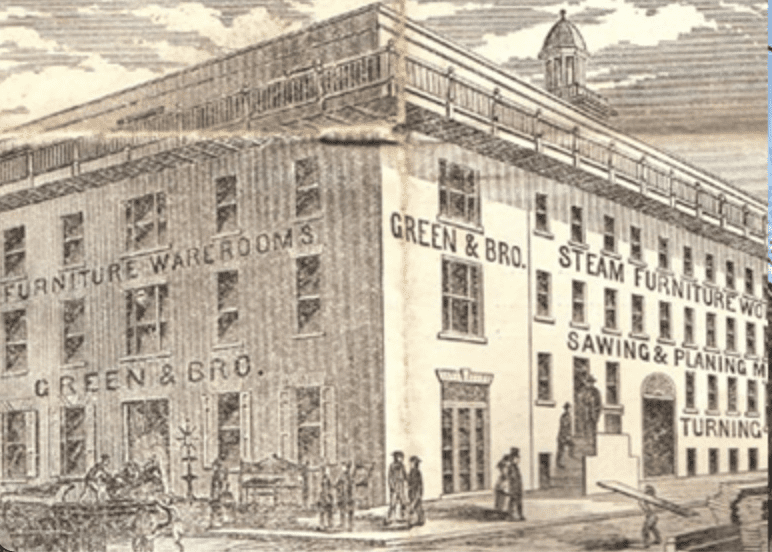

The warehouse where the fire began belonged to James Green (1801–1880), an English cabinetmaker who had immigrated to America with his father in 1817. Though the fire could have ended his career, Green rebuilt—and thrived.

By 1848, he had purchased the Old Bank of Alexandria at the corner of Fairfax and Cameron Streets and transformed it into the Mansion House Hotel, the largest in the city. During the Civil War, the Union Army seized the building and turned it into a military hospital. Green’s former furniture factory—rebuilt after the fire—was likewise repurposed as a prison.

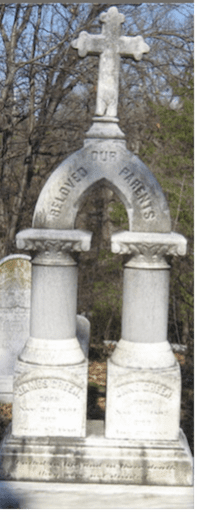

Though Green never took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union, he managed to maintain cordial relationships with Union officers and navigate the occupation years with his business intact. He died in 1880 and is buried at Ivy Hill Cemetery in Alexandria.

Emma Green and Mercy Street

James Green’s daughter, Emma Green, became the inspiration for a fictionalized version of the family’s wartime experiences. She was featured as a central character in the PBS drama Mercy Street (2016–2017), which was loosely based on the Green family and the Mansion House Hospital during the Civil War.

While the series dramatized many elements, the real Emma Green’s life was no less compelling—especially when viewed through her relationship with a man who became one of the Confederacy’s most legendary spies.

The Spy Who Married Emma

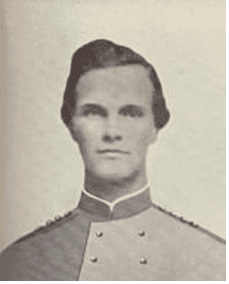

Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Stringfellow was slight in stature—just 5’8” and 94 pounds—but what he lacked in size he made up for in daring. A graduate of Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Stringfellow was initially turned away by several Confederate units due to his build. Eventually, he joined the 4th Virginia Cavalry and became a personal scout to General J.E.B. Stuart, conducting dangerous espionage missions deep inside Union territory.

One of the most memorable wartime stories tied to Stuart’s image involves a plume for his iconic hat—lost during a brief Union incursion at Verdiersville in 1862. That replacement plume may have come from Caroline Matilde Johnson, a devoted Alexandria Confederate supporter who smuggled medical supplies and other goods through enemy lines. Her act of bold defiance, hidden beneath the folds of a petticoat, became part of the personal mythology surrounding Stuart and those who supported him.

Read more about Caroline Matilde Johnson and the story behind the plume → “A Devoted Confederate Supporter with a Family Legacy of Military Service”

His exploits were so feared that the Union placed a $10,000 bounty on his head. Stringfellow operated undercover in Alexandria and Washington, D.C.—once posing as a dental assistant—and later earned a dental license to continue his intelligence work. Contrary to his portrayal in Mercy Street, he was never involved in any plot against President Lincoln.

After the war, Stringfellow fled to Canada rather than take the loyalty oath. He returned in 1867, enrolled at Virginia Theological Seminary, and became an Episcopal priest. He and Emma Green were married shortly after his return. Frank went on to serve congregations across Virginia and rejoined the military briefly as a chaplain during the Spanish-American War.

Frank Stringfellow died of a heart attack in 1913 and was buried beside Emma at Ivy Hill Cemetery, bringing their shared story full circle.

Echoes of Fire and War

The Great Fire of 1827 began in the heart of Alexandria’s industrial corridor, but its legacy reached far beyond property damage. It set in motion the rise of the Green family, whose personal and public lives would be shaped by fire, war, loyalty, and resilience. Their story—spanning multiple generations, a Civil War hospital, a spy ring, and national television—continues to echo through Alexandria’s cemeteries and streets.

And it all began with a spark on Royal Street.

Explore Further

- Visit the Green family graves at Ivy Hill Cemetery

Pay your respects to James and Emma Green, and Confederate scout Frank Stringfellow, all buried at one of Alexandria’s most historic cemeteries. - Learn more about Mercy Street and its ties to Alexandria

Discover how the PBS drama was inspired by the real-life Green family and the transformation of the Mansion House Hotel during the Civil War. - Join a guided walking tour of Alexandria’s Civil War history

Offered regularly by the Lee-Fendall House Museum, these tours bring to life the people, places, and events that shaped occupied Alexandria.

Sources of Information

Ivy Hill Cemetery. (n.d.). Welcome to Ivy Hill Cemetery. Retrieved from https://ivyhillcemetery.net

Matthews, P. K. (1988, July 29). The Great Fire of 1827: The account of the Alexandria Gazette, 23 January 1827[Annotated manuscript with addresses and map].

Weinraub, C. (n.d.). The Great Fire of 1827. Unpublished manuscript.