The Lee-Fendall House: Alexandria’s Historical Beacon

Situated at 614 Oronoco Street in Alexandria, Virginia, the Lee-Fendall House is more than just an architectural landmark. Built in 1785 by Philip Richard Fendall, the home reflects his legacy and the intricate tapestry of his life. Today, the Fendall burial mystery—whether he was truly laid to rest at Ivy Hill Cemetery—adds another layer to this fascinating story.

To read part 2 of this blog, click [here].

A Discovery That Piqued Curiosity

In the course of his research, David Heiby—a board member and public historian specializing in Alexandria’s cemeteries and burial grounds—encountered a striking claim: the FamilySearch website reported that Fendall was buried in Ivy Hill Cemetery in 1805. Yet Ivy Hill was not established until 1856, creating a chronological contradiction that demands closer investigation..

“Fendall passed away in March 1805 in Alexandria, District of Columbia, United States. He was 70 years old and was buried in Ivy Hill Cemetery, Alexandria, District of Columbia, United States.”

Citation on The Family Search Website

Understanding Philip Richard Fendall I

One must journey back to the man’s life central to it to fathom this enigma.

Born of Noble Lineage

Philip Richard Fendall, born in 1734, was a scion of the illustrious Fendall family, with connections to notable figures like Josias Fendall and Phillip Lee.

A Life of Service, Diplomacy, and Personal Endeavors

Fendall enjoyed a distinguished career that encompassed various roles, ranging from serving as the Clerk of Court for Charles County to making significant contributions during the 1778 Treaty of Alliance negotiations. He provided essential support to his cousin, Arthur Lee, who collaborated with Benjamin Franklin and Silas Dean to secure French assistance for the fledgling United States during the Revolutionary War against Britain. Simultaneously, Fendall’s personal life was punctuated by poignant moments, most notably his marriages:

Second Marriage: By 1780, Fendall’s heart found solace with Elizabeth Steptoe Lee. However, their union was empty of children, and Elizabeth departed in 1789.

Third Marriage: 1791 saw Fendall’s life enriched with the presence of Mary “Mollie” Lee. Their bond bore fruit with the birth of Phillip Richard Fendall II in 1794.

Laying Foundations in Alexandria

1784 marked a significant chapter in Fendall’s life as he acquired land in Alexandria, leading to the construction of the Lee-Fendall House in 1785. This establishment not only symbolized Fendall’s profound connection with the city but also became the nurturing ground for his son, Philip Richard Fendall, Jr. The house witnessed the upbringing of Fendall Jr., embedding itself deeply into the fabric of their family history. To explore more about Phillip Richard Fendall, Jr., including his attempts to manage affairs related to the Arlington House, visit https://gravestonestories.com/rebuffed-in-attempt-to-pay-tax-on-arlington-house/.

Hardship and Imprisonment

Despite his distinguished public service, the final years of Philip Richard Fendall’s life were overshadowed by mounting financial troubles. Like many in the post-Revolutionary South, he was “land rich but money poor.” At the height of his holdings, Fendall controlled more than 82,000 acres scattered across Virginia and Kentucky. Yet the agricultural depression of the 1790s caused land values to plummet, leaving him unable to translate vast acreage into liquidity.

By 1803, overwhelmed by debts and lawsuits, Fendall was confined to debtors’ prison. His release was secured only after friends and associates—including William Herbert, Richard Bland Lee, Thomas Swann, Robert Young, and William Byrd Page—established a trust to manage his property. Under its terms, none of his land could be sold without his consent, but Fendall remained deeply reluctant to part with acreage at depressed values. These struggles left him emotionally drained and financially ruined, a shadow that hung over his final years.

Piecing Together the Burial Mystery

Reverend James Muir’s diary entry from March 10, 1805, poignantly records the sudden passing of Philip Richard Fendall: “Mr. Fendall died this morning. He was in usual health last Lord’s Day and at church service. Taken ill on Monday.” The entry underscores the abruptness of his final illness. Although later records list Christ Church Cemetery1 as his burial site, Fendall’s will reflects both the weight of his financial troubles and his wish for a modest, dignified end. He wrote: “First, my will and desire that my body may be decently interred without pomp or show, my Burying Ground at my Farm…” These words bound his fate to the very land that had caused him so much difficulty in life. Even as lawsuits with the Hipkins family and other creditors dragged on, his instructions ensured that the family farm would also become his final resting place.

Fendall’s Enduring Legacy

The influence of Fendall’s life continued to echo long after his passing.

Mollie Fendall’s Wise Maneuver

In a savvy move in 1808, Mollie Fendall, Philip’s widow, leased the family estate to the esteemed tavern keeper, John Gadsby. This arrangement inadvertently connected the estate to a significant historical moment: the composition of the U.S. national anthem by Francis Scott Key. However, this partnership was short-lived, as Gadsby relinquished his lease upon relocating to Baltimore.

The Final Act of the Fendall Story

Following Gadsby’s departure in 1808, Mollie Fendall’s connection to the estate began to fade, symbolizing the conclusion of the Fendall family’s historical narrative. However, upon her death in 1827, Mollie was buried in the private cemetery on the farm, ensuring that the Fendall legacy would forever remain tied to this land.

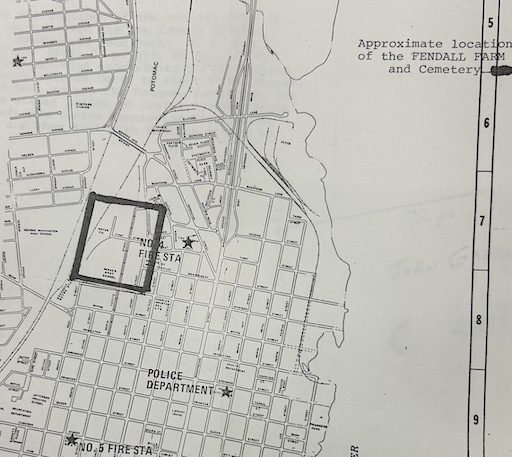

Contemporary Perspective on the Original Fendall Family Cemetery Site

The archaeological record and maps of the property remind us of a poignant irony: the farm that represented both Fendall’s greatest asset and his deepest liability also became his chosen burial ground. For a man besieged by creditors, the land was both a source of unrelenting financial strain and the sacred space where he wished to be remembered. In this way, his final resting place remains inseparably bound to the story of his decline and the enduring mark of the Fendall family on Alexandria’s landscape.

The Unresolved Mystery: Fendall’s Final Resting Place

Our journey into Philip Richard Fendall’s life and legacy has unveiled myriad facets, yet one enigma lingers in his final resting place. Part 2 of our exploration will traverse Alexandria’s transportation evolution, illuminating how progress might have uprooted Fendall from his initial burial site. Join us as we explore Ivy Hill Cemetery’s secrets, the potential resting place of Philip Richard Fendall, and the revelations that await. Stay tuned for an immersive historical and archaeological expedition.

Sources of Information

Archives of the Ivy Hill Cemetery. (n.d.). Access provided by Historian and Archivist Catherine Weinraub, with special thanks to Lucy Goddin, President of the Ivy Hill Cemetery Historical Society.

Baicy, D. (2019, December). Braddock Gateway: Archeological investigation and evaluation (WSSI #21677.03).Thunderbird Archeology. Prepared for Carmel Partners.

Bromberg, F. W. (n.d.). The history of Potomac Yard: A transportation corridor through time. Alexandria Archeology.

Dahmann, D. C. (2022). The roster of historic congregational members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. Old Presbyterian Meeting House Archivist.

Files and clippings about the Fendall Family. (n.d.). Alexandria Library, Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library, Local History and Special Collections Division, Alexandria, VA.

Griffin, W. E., Jr. (1984). One hundred fifty years of history: Along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad.Whittet & Shepperson.

Hahn, T. S., & Kemp, E. L. (1992). The Alexandria Canal: Its history & preservation (Vol. 1, No. 1). Institute for the History of Technology & Industrial Archaeology, West Virginia University Press.

Hopkins map of Alexandria County, Virginia: Includes the present Arlington County and the City of Alexandria. (ca. 1878).

Hurst, H. W. (1991). Alexandria on the Potomac: The portrait of an antebellum community. University Press.

Lee, C. G., Jr. (1957). Lee chronicle: Studies of the early generations of the Lees of Virginia. Published for The Society of the Lees of Virginia by Thomson-Shore.

Miller, T. M. (1985). Visitors from the past: A bi-centennial reflection on life at the Lee-Fendall House, 1785–1985. Lee-Fendall House.

Morgan, M. G. (n.d.). A chronological history of Alexandria Canal (Part II). Arlington Historical Society. Retrieved May 2023 from [URL]

Mullen, J. P. (2023, June). Braddock Gateway – Phase II. Cemetery investigation. Thunderbird Archeology. Prepared for Jaguar Development, LC.

Roberts, J. (2015). Jaybird’s Jottings: Rails in the seaport: A brief look at the history of railroads and their tracks in Alexandria. Retrieved from [URL]

Thunderbird Archeology. (2007). Documentary study for the Potomac Yard property, Landbays G, H, I, J, K, L, and M, City of Alexandria, Virginia. Gainesville, VA.

Workers of the Writer’s Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Virginia. (1940). Virginia: A guide to the Old Dominion. Oxford University Press.

- The Christ Church record likely reflects the common practice of listing parishioners in the church’s burial register, even if their remains were interred elsewhere. ↩︎