Situated at 1001 S. Washington Street, Alexandria, VA 22314, The Contrabands and Freemans Cemetery was founded in 1864 as a resting place for liberated individuals and escaped slaves who sought refuge in the town following the arrival of Federal troops on May 24, 1861.

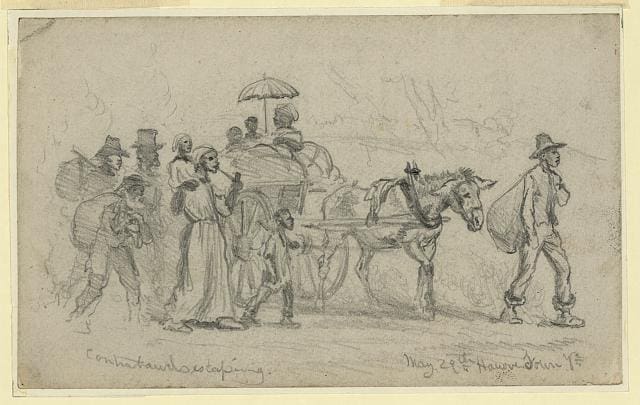

Contrabands of War

On May 24, 1861, shortly after Virginia’s secession, three escapees, enslaved people who the Confederacy had conscripted to construct batteries at Sewell’s Point, made their way to Union-held Fort Monroe in Virginia. Union General Benjamin Butler chose not to return these fugitives to their owners, designating them as “contraband of war” instead. Butler then enlisted them for labor on his fortifications. By the end of July, the fort had sheltered more than 900 contrabands. While the government officially sanctioned Butler’s strategy for enslaved individuals working for the Confederacy, this condition was frequently disregarded. As a result, during the war, countless enslaved individuals sought refuge in areas under Union control, including Alexandria.

For instance, the Wednesday, October 12, 1864 edition of the Alexandria Gazette recounted, “Alexandria was and remains a true city of sanctuary. Large numbers of refugee slaves from the South flock here—runaways in search of a taste and experience of the blessings of freedom. Presently, there are over seven thousand contrabands residing in Alexandria.”

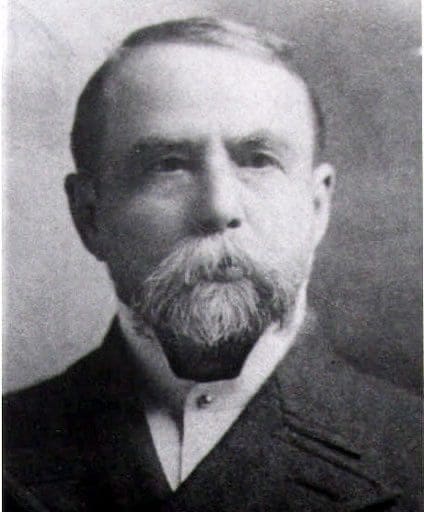

The Reverend Albert Gladwin, appointed Superintendent of Contrabands

To address the influx of refugees in Alexandria, Reverend Albert Gladwin, who relocated to Virginia in the winter of 1862-1863 under the auspices of the American Baptist Free Missionary Society of New York, assumed the role of Superintendent of Contrabands in 1863. Historical records indicate his affiliation with the Beulah Baptist Church in Alexandria, a congregation established in 1863 by formerly enslaved individuals, which also served as a site for a Contrabands school.

To accommodate the refugees, the government constructed barracks at various locations: the southern side of the 1200 block of Prince Street, the 800 block of Wilkes Street, the western side of the 400/500 block of South Columbus and Alfred Street, the northern side of the 1300 block of Wolfe Street, and the eastern side of the 200 block of Payne Street (Source: Wesley E. Pippinger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1868, also known as the Gladwin Record, and 1869-1896. Willow Bend Books. Westminster, Maryland. 1995. Page 3).

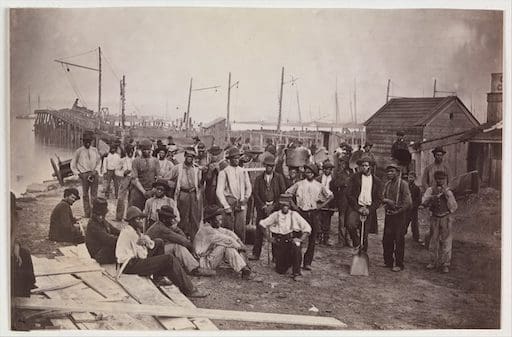

Additionally, the government engaged numerous Contrabands for manual labor roles in and around Alexandria, particularly in the docks area.

The Gladwin Record

In March 1863, Reverend Gladwin initiated the recording of the names of African Americans who passed away in Alexandria during the war. The Freeman’s Bureau oversaw this list until January 1869.

Referred to as the “Gladwin Record,” this roster remained lost until it was rediscovered in the Library of Virginia by Wesley E. Pippinger, a renowned historian, author, and genealogist.

The list encompasses 1879 names of the deceased. Regrettably, it does not encompass the approximately 1200 individuals who lost their lives in the initial two years of the war and are assumed to have been interred in Penny Hill Cemetery, which is part of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Numerous entries in the record provide details such as the deceased person’s place of residence, names of parents, and other noteworthy annotations.

Furthermore, the Gladwin Record documents marriages officiated by the Reverend starting from March 9, 1863.

Contrabands Hospitals

Numerous formerly enslaved individuals arrived in dire health, afflicted by illnesses such as smallpox and typhoid, often on the brink of death. On December 2, 1862, six wagons transported ailing contrabands to “Clermont,” once Commodore French Forrest’s residence. The property had been abandoned at the onset of the war. Clermont was positioned a few miles beyond Alexandria, situated off Old Fairfax Road, now recognized as Franconia Road. The 40th Governor of Virginia, Fitzhugh Lee, was born in Clermont on November 19, 1835. His parents, Sydney Smith Lee and Anna Marie Mason find their final resting place in the Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery.

Tragically, the majority of those who were hospitalized succumbed to their ailments. Some found their resting places at Clermont, while others were interred in Penny Hill. However, the largest portion were laid to rest in Alexandria’s Contraband and Freedmen Cemetery.

Following the war’s conclusion, those initially buried at Clermont were exhumed and reinterred in what was known as the “Contraband” or “lower” cemetery, which is now designated as Section 27 at Arlington National Cemetery (Dennee, 2015, p. 20).

The Contrabands and Freedmens Cemetery

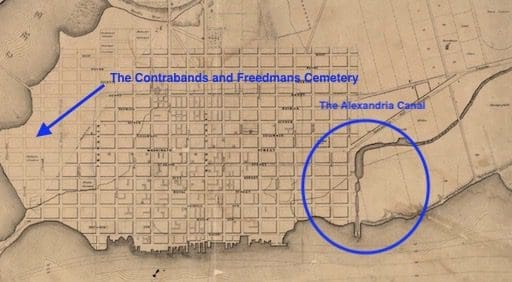

In the year 1864, Reverend Gladwin submitted a formal request for the appropriation of property on the southern periphery of the town, positioned at Broomallaw Point along Great Hunting Creek, which was the possession of Francis Lee Smith, Sr. This land was intended to be repurposed as a burial ground for contrabands and freedmen. Smith had fled to Richmond when federal troops took control of the town on May 24, 1861, and neglected to fulfill the legal requirement of paying taxes in person for the property.

As documented in the Gladwin Record: “Approximately one and a half acres of land owned by Francis L. Smith of Alexandria, situated at the far southern end of Washington Street, just beyond the city limits of Alexandria, was confiscated by military authority as abandoned in January 1864, according to the directive of Brigadier General John P. Slough of Ohio, who held the position of Military Governor of Alexandria.”

The initial interment within the newly established cemetery was that of five-year-old Morris Grimes on March 7, 1864. From that point until 1869, the cemetery received over 1700 Contrabands and Freedmen for burial, a significant number of them being women and children, all laid to rest without the presence of gravestones.

Randall Ward was employed with a wage of $20.00 per month, along with one ration and affordable lodging. Working alongside him was his assistant, Thomas Jackson, who received $15.00. Their duties led them to the cemetery every day, from dawn until dusk, to oversee the burials. Their lodging was situated in Building 3 of the Construction Corps barracks, found on the northern side of the 700 and 800 blocks of Gibbon Street.

A small structure was erected on the premises to house tools and biers, providing shelter for the grave diggers. (Source: Wesley E. Pippinger, “Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia,” Volume 2. Heritage Books. Westminster, Maryland. 2008. Page 9.)

The final funeral took place on January 12, 1869, for an 80-year-old woman named Millie Bailey. She resided near a coal wharf adjacent to the outlook lock of the Alexandria Canal on the Potomac River.

The Alexandria Canal, now defunct, was constructed to facilitate the movement of canal boats from the C&O Canal, which terminated in Georgetown, to Alexandria. Numerous of these boats transported coal from western Maryland. During the war, settlements, including shanties and Contraband houses, sprung up along the Alexandria Canal, forming neighborhoods like Petersburg (now known as The Berg), Grantsville, Pumptown, and Contraband Valley. Residents who passed away were interred in the Contraband and Freedmans Cemetery.

At 44 Canal Center Plaza in Alexandria, visitors have the opportunity to observe a meticulously restored lock from the former canal.

On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln endorsed the Emancipation Proclamation, liberating nearly 3 million enslaved individuals within the states that remained in opposition to the North and permitting the formation of regiments composed of freed and previously escaped slaves to fight on the side of the Union. More than 170,000 men answered this summons.

Petition Requesting Burial Rights in the Soldiers’ Cemetery

During the ongoing conflict, African American soldiers, known as the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), who passed away at the Grace Church Branch Hospital or L’Ouverture Hospital, found their final resting place in the Contraband and Freedmen Cemetery. (L’Ouverture Hospital was named after François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian general central to the Haitian Revolution, celebrated as the “Father of Haiti” for his leadership and strategic prowess in achieving Haitian independence.)

This decision dismayed surviving U.S.C.T. soldiers, who rallied for the recognition of their fallen comrades by advocating for their interment in the Soldiers’ Cemetery within the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

On December 27, 1864, a petition was signed by 443 soldiers who voiced their objection to the designation of “Contrabands” for themselves. They put forth a request for “…the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who differ only in color…” The petition further urged that deceased Black soldiers, interred in the Contraband and Freedmens Cemetery after passing away in Alexandria, be exhumed and reinterred beside their white comrades at the Soldier’s Cemetery on Wilkes Street. This appeal was directed to Major Edwin Bentley, who held the position of Surgeon in Charge of the military hospitals in Alexandria. It’s notable that Major Bentley resided in the Lee-Fendall House, which, during that period, functioned as an annex of the Grosvenor Branch Hospital.

Upon receipt of the petition, the United States Government concurred, and an order was issued to exhume and relocate the 118 U.S. Colored Troops interred in the Contraband and Freedmens Cemetery. However, Reverend Gladwin declined to comply with this directive. As a result, he was relieved of his duties in mid-January 1865.

Chaplain James Inglish Ferree, previously a Captain with the 9th Illinois Infantry and subsequently serving as a Hospital Chaplain in Washington, was promoted to Acting Superintendent of Contrabands at L’Ouverture Hospital. He inherited Gladwin’s responsibilities upon the latter’s dismissal. Ferree’s contributions led to his elevation to Superintendent of the Virginia Freedman Bureau in July 1865.

In January 1865, the government began burying deceased members of the U.S. Colored Troops in the Soldiers’ Cemetery. They also exhumed individuals previously interred at the Contraband Cemetery and reburied them in the Soldiers’ Cemetery.

(To view all the U.S.C.T. members buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, please visit this City of Alexandria website [link].)

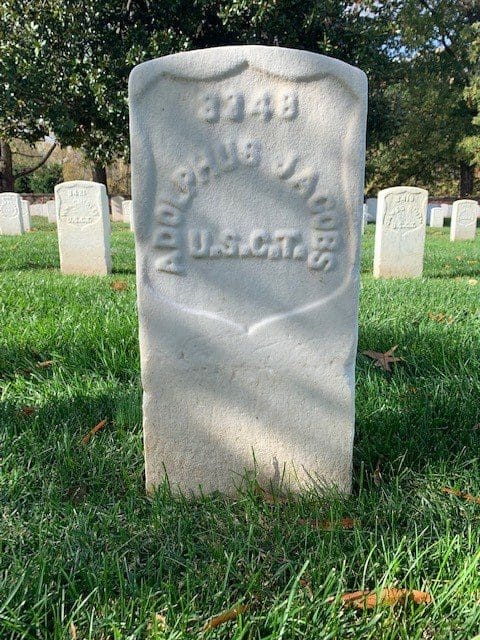

Private Adolphus Jacobs

Among those soldiers, Private Adolphus Jacobs served in the 28th Colored Infantry, Company D. On July 30, 1864, during the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia, he sustained a gunshot wound to his hip. Following his transport to Alexandria, he penned a letter back home, stating: “I never got over the hurt I received at the Charge at Petersburg, but I am as well as far as health is concerned as I ever was” (Source: Miller, Edward A. Jr. “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Soldiers in the Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II.” Alexandria Historical Quarterly. The Office of History Alexandria. Published Winter 1998. Page 2).

Regrettably, Private Jacobs’ condition did not improve, and he passed away at 22 on August 14, 1864, within the confines of L’Ouverture Hospital. His final resting place was the Contrabands cemetery. However, on January 20, 1865, his remains were disinterred and reinterred within the Soldier’s Cemetery.

Subsequently, twenty-three of the individuals who had signed the petition passed away and were also laid to rest in the Soldier’s Cemetery. Following the conclusion of the war, the cemetery underwent a renaming and became known as the Alexandria National Cemetery.

For additional insights, consider reading the blog titled [“Oh, give us a flag, All free without a slave,”] which delves into the narratives of Private Adolphus Jacobs and the experiences of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T) throughout the Civil War.

Gladwin and Ferree, after the war

Reverend Albert Gladwin, born on April 22, 1816, and facing accusations of racism and harsh treatment of contrabands during his time in Alexandria, transitioned into a role as a missionary for the American Baptist Publication Society. Unexpectedly, he passed away on November 14, 1869, in Laramie, Wyoming Territory, and found his final resting place in Prospect Hill Cemetery in Essex, Connecticut.

James I. Ferree, born in Ohio in 1822, concluded his service on March 3, 1866, and subsequently relocated to California. There, he took on the role of a mail agent for the California and Oregon Railroad while also delivering lectures on topics of religion and temperance. He passed away on May 16, 1891, and his resting place is within the Veterans Memorial Grove Cemetery in Napa County, California.

A forgotten cemetery is restored and dedicated to those buried within

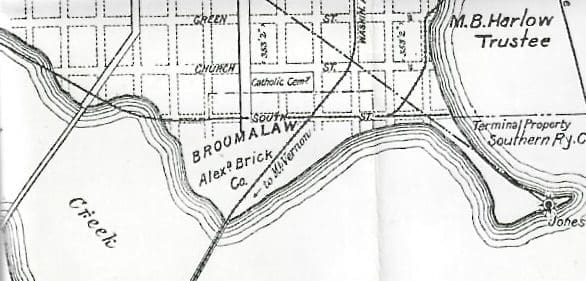

In 1872, the Freedmen’s Bureau was terminated by the United States Congress, primarily due to pressures exerted by southern white individuals. Subsequently, the cemetery gradually deteriorated. In a later period, the Smith family reclaimed the land, and in 1917, they sold it to the Catholic Diocese of Richmond, which maintained a nearby cemetery. Unfortunately, the cemetery’s edges were impacted by a brickyard and a railroad cutting, marked by the Southern Railroad’s right-of-way, as indicated on Harlow’s 1911 map (refer to the above).

Although the cemetery’s existence persisted on maps until 1939, any remaining above-ground evidence of burials had significantly diminished. As time went on, the site faded from memory, and in 1955, a gas station was established on the property, subsequently followed by the construction of an office building.

The long-forgotten cemetery was rediscovered in 1996 during historical research conducted before the rebuilding of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge. Archaeologists employed ground-penetrating radar, confirming the presence of the previously overlooked cemetery.

The establishment of The Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery in 1997 marked the inception of efforts to advocate for preserving the site as a memorial.

On September 6, 2014, the Contraband and Freedmens Memorial Cemetery was officially dedicated to commemorating those interred within its grounds.

Today, the cemetery is registered on the National Register of Historic Places, the Virginia Landmarks Register, and the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

The site welcomes visitors from sunrise to sunset throughout the entire year.

Sources of Information

City of Alexandria, Virginia. (2020). Contraband and Freedman Cemetery. Retrieved from [Contraband and Freedman Cemetery.] (Accessed 2020).

Convention of the Colored People of Virginia. (1865). Liberty, and equality before the law: Proceedings of the Convention of the Colored People of Va., held in the city of Alexandria, Aug. 2, 3, 4, 5, 1865. Cowing & Gillis, book and job printers. [https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/272]

Dennee, T. (2015). African-American civilians and soldiers treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865. Retrieved from http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf

Fairfax County Schools. (2019). Clermont Information. Retrieved from Fairfax County Schools website. (Accessed 2019). https://clermontes.fcps.edu/about/history/plantation

Friends of Freedman’s Cemetery. (2020). Official Website. Retrieved from [Friends of Freedman’s Cemetery.](Accessed 2020).

Furgurson, E. B. (2004). Freedom Rising, Washington in the Civil War. Vintage Books.

heotheralexandria. (2021). [theotheralexandria]. (Accessed 2021).

Historic Fairfax City, Inc. (2016). The Fare Facs Gazette. Volume 13, Issue 4. Fall 2016. Retrieved from [The Fare Facs Gazette. The Newsletter of Historic Fairfax City, Inc. Volume 13, Issue 4. Fall 2016]. (Accessed 2023).

McCargo Bah, C. (2019). Alexandria’s Freedman’s Virginia: A Legacy of Freedom. Edited by M. M. Bah. The History Press.

National Park Service. (2022). Fort Monroe and the Contraband of War. Retrieved from [Fort Monroe and the Contraband of War]. (Accessed 2022).

Pippinger, W. E. (1995). Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1868 (the Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896. Willow Bend Books.

Pippinger, W. E. (2008). Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia. Volume 2. Heritage Books.

Smithsonian. (2018). A Graveyard Resurrected: The Contraband and Freedmans Cemetery. Retrieved from [ A Graveyard Resurrected]. (Accessed 2022).

Tercha, J. (2017). Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System. Alexandria RiverRenew. Retrieved 2023.

Wenzel, E. T. (2015). Chronology of The Civil War in Fairfax County, or Battles and Skirmishes, Incidents & Events of The War Between the States Occurring in Fairfax County, Virginia, Part I. Bull Run Civil War Round Table.