How Following Presidential Orders Led to a Charge of Treason—and How the Evidence Finally Clears His Name

A Wednesday Afternoon Discovery in Special Collections

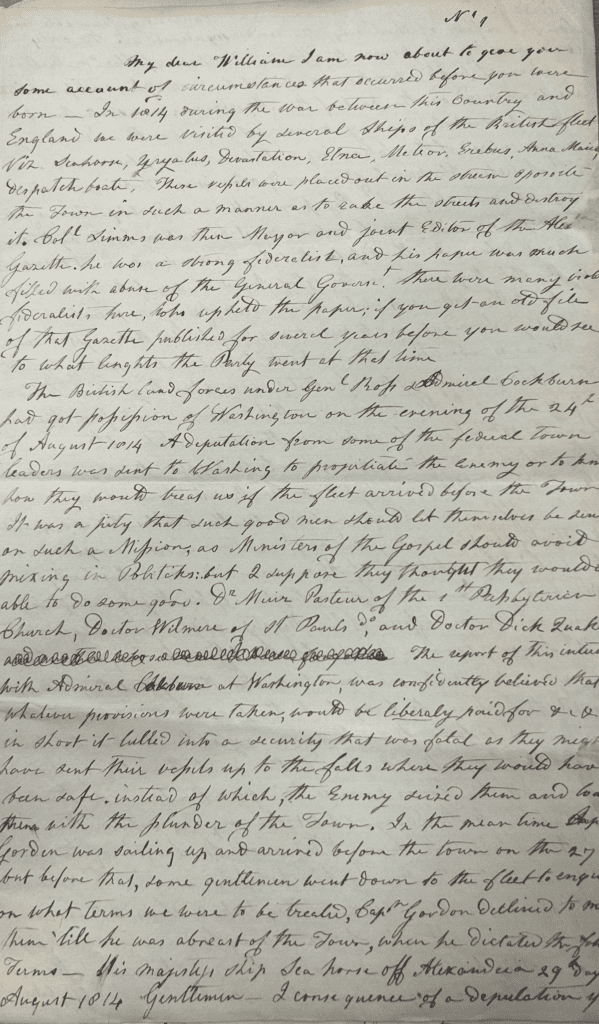

On Wednesday, January 15, 2026, historian Catherine Weinraub sat in the Special Collections room at Alexandria’s Kate Waller Barrett Library, working through Box 240 of the Cazenove Family papers. She pulled out a folder cryptically labeled “CAZENOVE LETTER RE: SURRENDER OF ALEXANDRIA.” The archival title initially pointed toward a Civil War context—a reasonable assumption that reflects how thoroughly Alexandria’s War of 1812 surrender has been eclipsed in public memory. This discovery ultimately revealed and resolved the Cazenove treason accusation, a charge that had been entirely forgotten since the War of 1812.

Inside were approximately 20 pages of dense handwriting—both an original period letter and a careful transcription. As Catherine began reading the fragile original, she quickly realized she was holding something extraordinary: a detailed family defense against accusations of treason during the War of 1812.

She handed me the handwritten transcription to read while she continued with the original. As I worked through page after page, the scope of what we’d found became clear. This wasn’t just another War of 1812 document—it was an eyewitness account of Alexandria’s most humiliating moment, reinforced by General John Mason’s sworn testimony to Congress, contemporary newspaper defenses, and a family record documenting how political enemies attempted to destroy an innocent man.

This article is based on the archival discovery of the Cazenove Letter by historian Catherine Weinraub, whose work made this research possible.

I photographed every page. What follows is the story those pages tell—and the remarkable evidence that finally, after 210 years, completely vindicates Anthony Charles Cazenove.

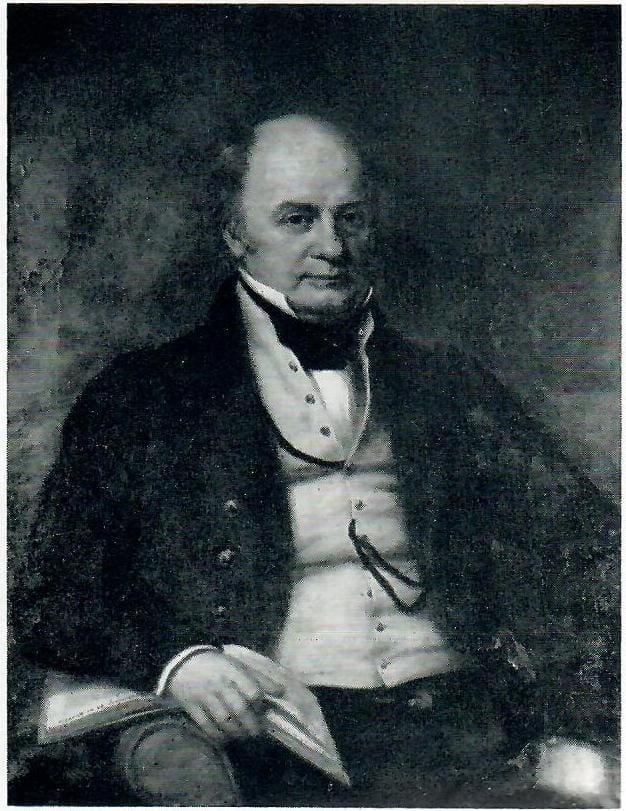

Anthony Charles Cazenove: The Man They Tried to Destroy

Before we tell you what happened, you need to understand who Anthony Charles Cazenove was—and why the accusations against him were so devastating.

Anthony Charles Cazenove (April 6, 1775 – October 16, 1852) was born in Geneva, Switzerland, to a prominent French Huguenot family that had fled religious persecution in France. During the French Revolution, he and his brother were imprisoned before being released and sent by their parents to Philadelphia, where they had relatives.

Cazenove arrived in Alexandria in 1799. In 1800, he secured a position with E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company, distributing gunpowder throughout the Southern states—a role that would prove deeply ironic given later accusations. He eventually founded his own company, A.C. Cazenove & Company, and became a director of the Bank of Alexandria. His warehouses stood at 101 and 103 King Street.

By 1814, Cazenove was a respected pillar of Alexandria society. He would later serve as Swiss Consul for the middle and southern states from 1822 until his death in 1852—a thirty-year diplomatic career. He served as Ruling Elder at the Old Presbyterian Meeting House1 for 36 years. He helped establish the Alexandria Water Company and founded the Mount Vernon Manufacturing Company.

In October 1824, Cazenove had the honor of hosting the Marquis de Lafayette during his triumphant return to America. He introduced Lafayette to the assembled crowd at the Lawrason House on St. Asaph Street 2. Lafayette later described his time in Alexandria as “the most enjoyable hours of his life.”3

When Cazenove died in 1852, his gravestone in the Presbyterian Cemetery recorded that he was “universally respected and beloved.”

But in January 1815, Federalist enemies tried to brand this man a traitor.

August 1814: The British Are Coming

The letter written to Cazenove’s son William begins simply:

“My dear William I am now about to give you some account of circumstances that occurred before you were born—in 1814 during the war between this Country and England we were visited by a British fleet.”

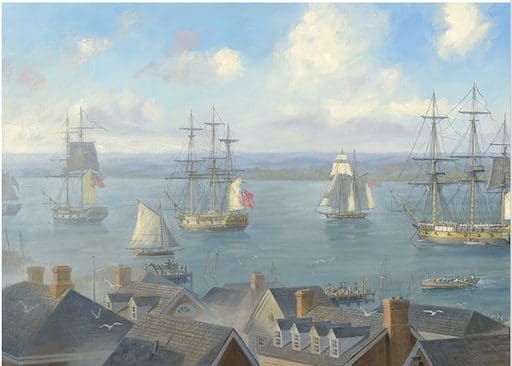

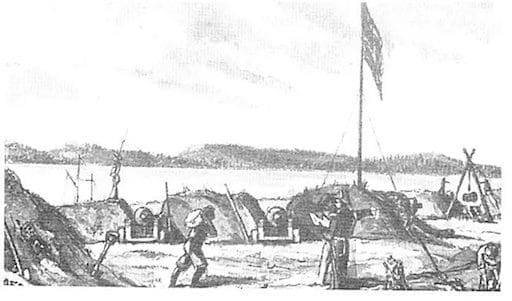

In late August 1814, following the British army’s burning of Washington, D.C., a powerful British naval squadron advanced up the Potomac River. Anchoring opposite Alexandria, the fleet—including bomb and rocket ships such as Erebus and Meteor—positioned itself to rake the town’s streets and force its surrender.

Alexandria had no federal troops for defense. Mayor Charles Simms faced an impossible choice: fight and be destroyed, or surrender and hope for mercy4. On August 29, 1814, Captain James Alexander Gordon5 of HMS Sea Horse dictated his terms.

The British demanded all naval stores and ordnance, all shipping, sunken vessels, all merchandise, and refreshments at market price. In exchange, Gordon promised the town would not be destroyed, and the inhabitants would not be molested.

The Mayor and Common Council had one hour to decide. They had no choice. They agreed.

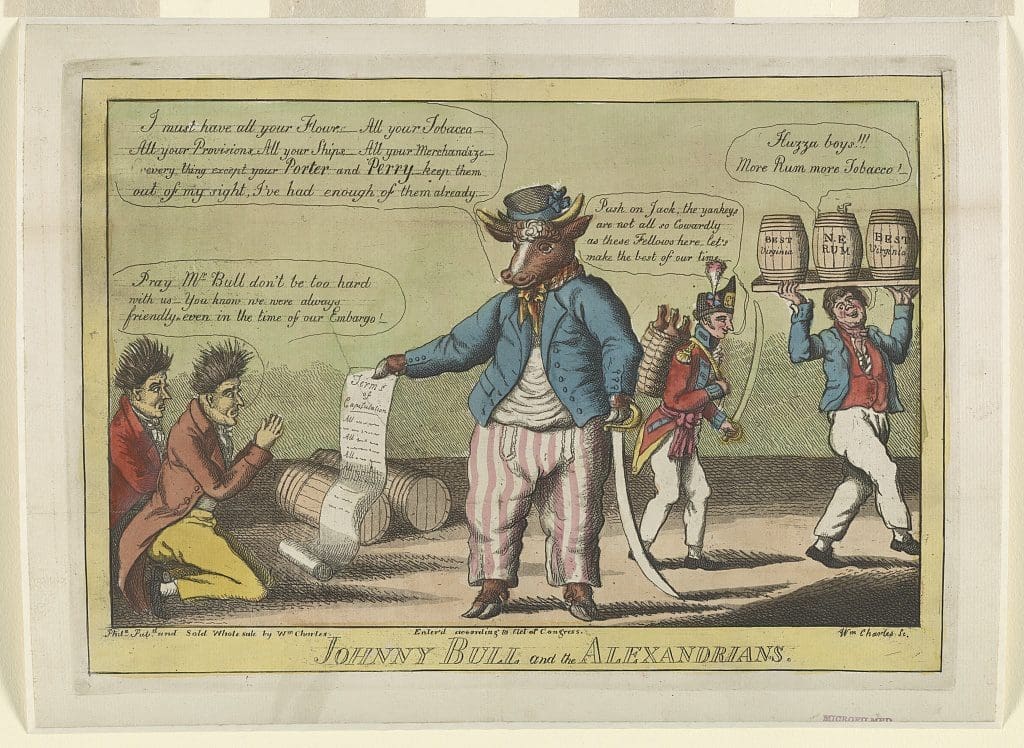

The Plunder

For three days—August 29, 30, 31, and into September 1st—the systematic looting continued. The British seized 16,000 barrels of flour, about 1,000 hogsheads of tobacco, 150 bales of cotton, wine, sugar, coffee, cigars, sails, and ropes worth approximately $5,000, and 21 vessels from Alexandria’s port. They left behind 220,000 barrels of flour—simply too much to transport.

The letter includes a vivid detail that captures the humiliation:

“All the horses were carried from the town so the sailors were hitched to the [carts] whilst loading the vessels.”

Alexandria’s residents had evacuated their horses, forcing British sailors to pull carts like draft animals through the streets.

Cazenove Goes to Washington: A Meeting with President Madison

While the British occupied Alexandria, Anthony Charles Cazenove traveled to Washington. There, he called on President James Madison himself.

During their conversation, Cazenove learned of a remarkable development. A letter had been intercepted—purportedly from Rear Admiral Codrington6, ordering Captain Gordon to withdraw from the Potomac immediately. The letter had come through American military camps, carried by a countryman, and had been seized by American forces.

But there was a complication. At the same time, another dispatch from Admiral Cochrane had arrived—this one ordering the British fleet to “destroy and lay waste all the assailable towns.” Here was a direct contradiction. Was the Codrington letter genuine? Or was it a British trick?

The Americans tested the paper for hidden messages. Secretary of State James Monroe—then also acting as Secretary of War—took charge of the matter.

Cazenove expressed a wish that Alexandria might have the benefit of the letter. What happened next would nearly destroy his reputation.

The Intercepted Letter: Evidence That Changes Everything

Before we continue with Cazenove’s story, we need to explain a crucial piece of evidence that historians have only recently uncovered.

In Patrick O’Neil’s detailed study “To annoy or destroy the enemy”: The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington (2014), there is a reference on page 136 that transforms our understanding of this entire controversy.

Colonel Athanasius Fenwick of the 12th Regiment of Maryland Militia wrote to Secretary of State Monroe reporting that his forces had intercepted a letter destined for Captain Gordon from Rear Admiral Codrington. The letter was being carried by an unnamed American officer. The gist of the order was clear: Gordon was “to retire from the Potomac immediately.”

Fenwick asked the American courier whether he intended to deliver the order as directed. The courier confirmed he did.

Fenwick then “ordered him most positively not to do so.”

The letter was real. It wasn’t a British ruse. Codrington actually sent an order for Gordon to withdraw.

American military forces deliberately suppressed it. Fenwick made a tactical decision: if Gordon didn’t know he’d been ordered to withdraw, he might linger at Alexandria—giving American forces more time to prepare the batteries that would savage his squadron on the way downriver.

This means that before Cazenove ever received the letter, American military commanders had already decided it would never reach Gordon.

General Mason’s Testimony: The Smoking Gun

The Cazenove letter preserves General John Mason’s sworn testimony to Congress, dated October 31, 1814. It is the most important document in this entire affair7.

Mason testified that on the morning of August 31, 1814, “some hours before day,” a dragoon express woke him with a packet from Admiral Cochrane. While Mason examined the dispatch, the dragoon mentioned that the British ships at Alexandria had been ordered to withdraw by an open note from Codrington.

Mason immediately went to Monroe, “although not yet day,” and delivered the information. Later that day, around 1 o’clock, Monroe showed Mason the open note itself, which had been brought up by an American officer from the camp.

Mason’s testimony reveals Monroe’s thinking:

“Col. Monroe took this view of the subject and expressed his suspicion that the note was a forgery, and the probability if it was genuine, that by previous concert it might be the very reverse of what appeared on its face.”

The Americans were suspicious. Why would Cochrane suddenly express concern for Alexandria’s inhabitants when the British had spent two years “in the constant habit of burning and carrying off” property? Why send the order by land when “communication by water was open to him”?

But Monroe made a decision. Mason testified:

“Under these circumstances, and in the then state of things, a preparation going on to intercept the British ships below Alexandria, some doubts were entertained of the propriety of permitting it to pass to them; he, however, determined that it should be disposed of in such a way as to let the citizens of Alexandria have the benefit of it, if benefit there was, and at the same time to keep the enemy in ignorance that the government had any knowledge of it.”

This was Monroe’s explicit order: Let Alexandria benefit if possible, but keep the British ignorant that the American government had intercepted the letter.

Monroe requested Mason to deliver the note to “a gentleman of Alexandria” with instructions to “give it such a course immediately.”

About an hour later, Mason put the letter into the hands of Anthony Charles Cazenove.

Cazenove’s Solution: Approved by Mason

Here is where the Federalist accusation completely collapses.

Mason’s testimony continues:

“He undertook the charge with great cheerfulness and suggested as the best mode of answering the purpose intended, that he would place it in the post office at Alexandria, under cover, addressed to one of the acting committees of the town, remarking that it would reach them in that way almost as speedily as if he were to deliver it himself, and that by this means, the committee and himself would be relieved from embarrassment, if the committee were called upon to answer by the officers of the enemy, in whose power they were, as to the channel through which it had been received.”

Cazenove’s reasoning was brilliant. The Committee of Vigilance was under British occupation. If they received a letter directly from Cazenove, and the British demanded to know how they got it, they would face an impossible choice: lie to armed occupiers, or reveal that the American government had intercepted British communications.

By placing it in the post office, addressed to the Committee, it would appear to have arrived through normal channels. The Committee could honestly say they found it in the mail. The American interception would remain secret.

Mason’s verdict on this plan:

“I thought his reasons good and approved of the mode he proposed to adopt.”

General Mason explicitly approved Cazenove’s method. Cazenove was not exercising questionable judgment. He was not being careless. He proposed a solution, explained his reasoning, and received approval from the man acting on Monroe’s direct orders.

Mason confirmed: “That he did so deposite the note in the course of the same afternoon. I was informed by him on the next day; and I have no question of the fact.”

The Timeline: What Actually Happened

The family letter provides the precise sequence:

Cazenove deposited the letter in the post office at 10 o’clock on the night of August 31st, addressed to the Committee of Vigilance. He then went to Summer Hill, the Cazenove family’s country house about a mile from town.

On September 1st, Cazenove left for Fauquier County in Virginia on business—collecting debts owed to him. He wrote to General Mason from Fairfax Court House, 15 or 16 miles away, confirming he had placed the letter in the mail box.

Young Gilpin, son of the Postmaster, came to the office daily. J.M. Swearson of the house of Lawrason & Fowle was the first person to see the letter on the morning of September 2nd. He said to Gilpin, “This letter ought to be sent to the Committee.”

The letter had lain in the box from 10 p.m. on August 31st to the morning of September 2nd—about 36 hours.

But as the family letter notes:

“As I remarked before, the British were done plundering. Had told their friends to have their letters ready for England the day before. And every one knew that Batteries were preparing at the White House, and Indian Head.”

The British were already leaving. The letter was irrelevant.

What Actually Made the British Leave: Mason’s Testimony

General Mason’s testimony delivers the final blow to the Federalist accusation. He explains what actually caused Gordon to withdraw:

“There is one fact notorious on this subject: that he ceased to levy contributions on the town of Alexandria about the middle of the day on which Commodore Porter’s battery reached the White House (the position below Alexandria selected from which to annoy him in his descent) and that he immediately after began to draw off his ships from the station he had taken before the town. This was on the first day of September.”

Mason continues:

“Commodore Porter’s artillerists and General Young’s Brigade crossed the ferry at Georgetown, on the expedition, at the commencement of the night of the 31st August. That this movement was known to the enemy on the next day and instantly arrested his devastations at Alexandria, I have never had the slightest doubt.”

Mason was an eyewitness: “As to time and circumstance of the movement, I cannot be mistaken, as I was with both the corps during that night, one of their encampments, and the other on their march.”

The British left because of Porter’s batteries—not because of any letter. Gordon saw American artillery being positioned to destroy his squadron on the way downriver. He knew it was time to go. The Codrington letter—whether it reached him or not—was irrelevant to his decision.

The Battle Downstream: Gordon’s Gauntlet

What happened next proved Mason right.

On September 2nd, as Gordon’s squadron began moving downstream with 21 prize vessels laden with Alexandria’s plunder, they faced the batteries that had caused them to flee. For four brutal days—September 2-5, 1814—the British fought their way past American defenses at the White House Landing.

The engagement was fierce: over 700 mortar shells fired by the British, Congreve rockets lighting up the night sky, hand-to-hand combat when British boats tried to silence the batteries. The bombardment could be heard as far as Georgetown.

American casualties: 12 killed, 17 wounded. British casualties: 7 confirmed killed, 35 wounded, including three of Gordon’s subordinate captains.

Among the American dead was Private Robert Allison Jr., age 27, grandson of Alexandria founder William Ramsay. His gravestone in the Presbyterian Cemetery reads:

“ROBERT ALLISON, Jr. who fell in batle on the 5th Septr. 1814 at the white house in gallantly defending his country aged 27 years. Our lives belong to God, & our country.”

General Robert Young, who commanded the American forces, is also buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery—near the young soldier who fell under his command, and near the Cazenove family plot.

The Battle of the White House so enraged Admiral Cochrane that he immediately advanced his timeline for attacking Baltimore. This decision led directly to the bombardment of Fort McHenry on September 13-14, 1814, where Francis Scott Key witnessed the “rocket’s red glare” and wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Cazenove Treason Accusation: January 1815

Months passed. Alexandria began to recover. And then, on January 28, 1815, the Alexandria Gazette—published by Snowden and Simms—dropped a bombshell.

Under the headline “Admiral Codrington’s Letter,” the Gazette accused a “highly respectable citizen” of deliberately suppressing the British withdrawal order:

“…the greatest part of [the] loss they sustained by the late depredations of the enemy was occasioned by the unpardonable conduct of a highly respectable citizen of their own town, at present concealed from public view; but who should be better known.”

The article accused this citizen of allowing Alexandria’s plunder to continue for “personal motives.” It called on “the injured citizens to find out this highly respectable citizen and his personal motives for silently viewing their destruction.”

The family letter records the reaction:

“This publication caused argument and enquiry ran round and questions were asked who is the person this is aimed at?”

Dr. James Carson—a prominent Alexandria physician, War of 1812 veteran, and pillar of the community—called on Cazenove and asked if he knew who the accused citizen was8.

Cazenove “at once avowed himself.”

But he wanted to write to General Mason first, to establish the facts before responding publicly.

The Real Motive: Political Revenge

The family letter reveals what was really behind the attack:

“Many were satisfied at once, that a man possessing his property, and respectability of character, could not wish to see the town injured, but the hot violent federalists, tried to keep up a party about it. Some of them had been displeased with his taken some of the United States loans, and him that he was lending his money in an unrightious cause.”

The real issue wasn’t the letter. It was politics.

Cazenove had purchased U.S. government war bonds—he was financially backing Madison’s war against Britain. The Federalists, who generally opposed the war and favored commercial ties with Britain, saw this as “lending his money in an unrighteous cause.”

The Codrington letter was just a convenient weapon to attack a man they already despised. They wanted to destroy a Democratic-Republican who had put his money where his politics were.

The letter notes that the Gazette article contained “many falsehoods or errors.” The post office box was not nailed up—“letters were daily thrown into the letter boxes usual.” The mail was operating normally despite the occupation.

The Vindication

The Federalists overplayed their hand.

When they learned that Cazenove was preparing to publish General Mason’s letter and his own correspondence with that gentleman, the attack collapsed. The family letter records:

“Then Mr. Smith and Mr. Hoffman carried the letter to the Coffee house, and there it was submitted to their examination and the storm was hushed up for the time.”

The public examination of the evidence vindicated Cazenove completely.

We were told that George Daniel was the writer of that publication—the man behind the Gazette attack.

The Democratic gentlemen who supported the government wanted to counterattack—to continue the newspaper war and destroy Cazenove’s accusers. But Cazenove himself chose peace:

“The Democratic Gentlemen who were then on the side of Government wanted to take up the feud but your father, for peace, put a stop to any further publications on the subject.”

One defense piece written by Mr. A. McClean was sent to the Herald office. The editor submitted it to Cazenove for approval before publishing. Cazenove had the power to continue the fight—and he chose not to.

A defense letter to the Herald, dated February 7, 1815, survives in the family papers. It calls the Gazette attack “base and malignant misrepresentation” and an attempt at “assassination of private character.” It notes that publishing Mason’s letter would let “those who have really been deluded by the garbled article in the Gazette” judge for themselves.

The Complete Picture: Total Vindication

With the evidence from the Cazenove family letter, General Mason’s Congressional testimony, and Patrick O’Neil’s research on Colonel Fenwick’s interception, we can now state definitively:

Anthony Charles Cazenove was completely innocent.

He met with President Madison and learned of the intercepted letter. Secretary of State Monroe ordered that it be delivered secretly to protect the American interception. General Mason delivered it to Cazenove with explicit instructions. Cazenove proposed a method to protect both the Committee and the secrecy of the interception. Mason approved that method. Cazenove executed it exactly as approved.

Meanwhile, Colonel Fenwick had already intercepted the original letter and ordered it not delivered to Gordon. The letter was never going to reach the British anyway.

And even if it had, it wouldn’t have mattered. The British left because of Porter’s batteries, not because of any letter. Mason testified to this under oath.

The Federalists attacked Cazenove for following explicit orders from the Secretary of State, using a method approved by General Mason, regarding a letter that had already been suppressed by military order, about a withdrawal that was caused by military action, not correspondence.

Every element of the accusation was false.

The full documentary record now allows the Cazenove treason accusation to be evaluated on evidence rather than rumor, restoring a reputation unjustly damaged in 1815.

The Rest of His Life: Universally Respected and Beloved

Anthony Charles Cazenove lived another 37 years after the controversy.

In 1822, the Swiss Federal Diet selected him to serve as consul for the middle and southern states—a position he held until his death, a testament to his international standing and reputation for integrity.

In October 1824, Cazenove hosted the Marquis de Lafayette during his triumphant American tour. He introduced Lafayette to the cheering crowds at the Lawrason House. Dr. James Carson—the same man who had confronted Cazenove about the letter nine years earlier—organized the civic escort for Lafayette. Whatever tension had existed between them was long forgotten.

Cazenove continued to serve his community. He helped establish the Alexandria Water Company. He served as Ruling Elder at the Old Presbyterian Meeting House for 36 years. His home at 414 N. Washington Street, built in 1840, was considered one of Alexandria’s finest examples of Greek Revival architecture.

On Saturday, October 16, 1852, Anthony Charles Cazenove passed away at the age of 78. His obituary in the Alexandria Gazette—the same newspaper that had attacked him 37 years earlier—recorded that he was “universally respected and beloved.”

His gravestone in the Presbyterian Cemetery reads:

“In memory of ANTY. CHAS. CAZENOVE a native of Geneva Switzerland but for nearly 60 years an esteemed citizen of Alexandria where he departed the life on Saturday the 16th day of Oct. 1852 in the 78th year of his age universally respected and beloved.”

The Federalists tried to destroy him. They failed. History vindicated him in his lifetime. And now, 210 years later, we can prove exactly why they were wrong.

The Letter’s Journey

The Cazenove family letter was written to William Gardner Cazenove, one of Anthony’s ten children, sometime after November 1824. The writer wanted William to understand what his father had endured—and how he had been vindicated.

Someone in the family—perhaps William himself—recognized the letter’s historical importance and carefully transcribed it by hand, preserving both the original and the copy together.

Both documents were preserved in the Cazenove Family papers, which eventually made their way to Alexandria Library Special Collections. There they sat in Box 240, catalogued simply as “CAZENOVE LETTER RE: SURRENDER OF ALEXANDRIA,” waiting for someone who would understand their significance.

Until Wednesday, January 15, 2026, when Catherine Weinraub opened that folder.

William Gardner Cazenove (1819-1877) is buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery—Section 43, Plot 107—near his father’s obelisk9.

Photo by David Heiby.

Why This Matters

The Cazenove letter, combined with O’Neil’s research on Colonel Fenwick, is significant for several reasons.

It reveals President Madison and Secretary Monroe’s direct involvement in trying to help Alexandria during the British occupation—and the sophisticated reasoning behind their orders.

It preserves General Mason’s sworn Congressional testimony explaining exactly how the letter was handled and why.

It proves that Cazenove’s method was explicitly approved in advance by Mason, acting on Monroe’s orders.

It documents that the British left because of Porter’s batteries, not any letter—making the entire accusation moot.

It reveals the political motivation behind the attack: Cazenove’s purchase of U.S. war bonds.

It shows Cazenove’s character in choosing peace over revenge when he had the power to destroy his accusers.

And it completely vindicates an innocent man, 210 years after political enemies tried to brand him a traitor.

A Personal Note

As historians who spend our lives researching Alexandria’s cemeteries and buried history, moments like this—when Catherine handed me that transcription on Wednesday afternoon—are what we live for.

Anthony Charles Cazenove rests in the Presbyterian Cemetery, Section 43, Plot 107. His obelisk rises above the surrounding stones. His epitaph calls him “universally respected and beloved.”

Near him lies his son William, who received the letter explaining what his father endured. Near them both lie Robert Allison Jr., who died at the White House batteries that actually caused the British to flee, and General Robert Young, who commanded those batteries.

Dr. James Carson, who confronted Cazenove in 1815 and organized Lafayette’s escort in 1824, rests in Christ Church Cemetery nearby. General John Mason, who delivered Monroe’s orders and approved Cazenove’s method, is also buried in Christ Church.

These men knew each other. They lived through the same crisis. Some accused, some defended, some fought, some died. And now they rest within walking distance of each other in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

That’s what primary sources do. They take names on gravestones and transform them back into human beings—complicated, flawed, sometimes falsely accused, but deserving of the truth.

Anthony Charles Cazenove deserves to be remembered as what he was: a patriot who served his adopted country, followed orders from the highest levels of government, and when political enemies tried to destroy him, chose peace over vengeance.

His family preserved the evidence. They knew he was innocent. They were right.

And 210 years later, on a Wednesday afternoon in January 2026, Catherine Weinraub found that evidence waiting in a box at the library.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the Alexandria Library Special Collections at the Kate Waller Barrett Library. We thank the staff for their preservation of the Cazenove Family papers and their assistance in accessing these materials.

Special appreciation to the Cazenove family, who preserved these documents for generations before they entered the public archives, recognizing that private family history is also public history.

Thanks also to the historians and archivists who have preserved Alexandria’s War of 1812 history, including Walter Lord (The Dawn’s Early Light), Steve Vogel (Through the Perilous Fight), and Patrick O’Neil, whose research on Colonel Fenwick’s interception provided crucial corroborating evidence.

About the Authors

David Heiby is Superintendent of the Presbyterian Cemetery in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex and serves as Treasurer of both the Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation and the Alexandria Historical Society. He serves on the Alexandria Archaeology Commission Subcommittee working to gain National Register status for the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex. David is the owner and founder of Gravestone Stories, an online digital platform documenting Alexandria’s cemeteries that serves as a digital museum for researchers and genealogists. In 2024, working with archaeologist Mark Ludlow, he rediscovered George Washington’s lost pallbearer Colonel George Gilpin using ground-penetrating radar. Working with research partner Catherine Weinraub and archaeologist Mark Ludlow, he also rediscovered Philip Richard Fendall I and Charles Glasscock.

Catherine Weinraub is a historian and tour guide with Gravestone Stories, historian for the Friendship Veterans Fire Engine Association and Ivy Hill Historical Society. She leads tours of Ivy Hill Cemetery and conducts original research in Alexandria’s archives. Her discovery of the Cazenove letter at Alexandria Library Special Collections on January 15, 2026 provides crucial new insight into one of Alexandria’s most controversial moments during the War of 1812—and completely vindicates a man falsely accused of treason.

Related Reading on Gravestone Stories

The Battle of the White House: Robert Allison Jr.’s Sacrifice

Dr. James Carson: War of 1812 Veteran

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex: America’s Most Historic Cemetery Cluster

Have you visited these historic graves? Share your experience in the comments below, or contact us to book a guided tour of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex where many of these figures are buried.

Sources of Information

Primary Sources

Manuscript Collections:

Cazenove Family Papers, Box 240. Alexandria Library Special Collections, Kate Waller Barrett Library, Alexandria, Virginia. “CAZENOVE LETTER RE: SURRENDER OF ALEXANDRIA.” Original letter and handwritten transcription. Includes General John Mason’s testimony to the Committee of Congress, October 31, 1814, and defense letter to the Herald editors, February 7, 1815.

Contemporary Newspapers:

Alexandria Gazette (Snowden & Simms). (1815, January 28). Article accusing “highly respectable citizen” of suppressing Admiral Codrington’s letter.

Alexandria Gazette. (1814, September). Reports on British occupation and Battle of the White House.

Alexandria Gazette. (1852, October 18). Obituary of Anthony Charles Cazenove.

Secondary Sources

Articles and Monographs:

Beirne, F. F. (1965). The War of 1812. Hamden, CT: Archon Books.

Horsman, R. (1969). The War of 1812. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lamond, T. (1962, August 29). Alexandria forced to surrender to the British on August 28, 1814. Alexandria Gazette.

Lamond, T. Port of Alexandria next British target after Washington. Alexandria Gazette.

Lord, W. (1972). The Dawn’s Early Light. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Moore, G. M. (1949). Seaport in Virginia: George Washington’s Alexandria. Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie.

O’Neill, P. L. (2014). “To annoy or destroy the enemy”: The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington(p. 136).

Vogel, S. (2013). Through the perilous fight: Six weeks that saved the nation. New York, NY: Random House.

British Primary Sources:

“British Warships at Alexandria, Virginia 1814” (The English Viewpoint as recorded by the Log of the H.M.S. Seahorse, 27 August – 2 September 1814). Information from the Public Record Office, London, quoted by Captain Donald E. Willman (U.S.N. retired). Copy in Alexandria Public Library.

Letter from Captain James A. Gordon to Admiral Cochrane, dated September 9, 1814.

Note on the Cazenove Letter

The Cazenove letter, the primary source for this article, is housed in the Cazenove Family Papers (Box 240) at Alexandria Library Special Collections. Both the original period letter and a complete handwritten transcription are preserved together. The letter was discovered by historian Catherine Weinraub on January 15, 2026.

Internal evidence indicates the letter was written after November 1824, addressed to William Gardner Cazenove (1819-1877), one of Anthony Charles Cazenove’s ten children.

The letter preserves General John Mason’s October 31, 1814 testimony to the Committee of Congress, contemporary newspaper articles, and a defense letter dated February 7, 1815.

Researchers wishing to examine the original document should contact Alexandria Library Special Collections at the Kate Waller Barrett Library, 717 Queen Street, Alexandria, VA 22314.

- The Old Presbyterian Meeting House

The Old Presbyterian Meeting House, erected in 1775 and reconstructed in 1837 following a destructive fire, is one of Alexandria’s most significant surviving historic buildings and a rare example of Reformed-Protestant “plain style” Georgian architecture. Designed as a Domus Ecclesia—a house for the gathered congregation—it emphasizes the spoken Word through a centrally placed pulpit and acoustically focused interior rather than ornamentation. The Meeting House served as a focal point for Alexandria’s religious, civic, and commemorative life, including memorial services for George Washington in 1799, and it remains a National Historic Landmark. ↩︎ - The Lawrason House and Lafayette’s 1824 Visit

The Lawrason House, located at 301 S. St. Asaph Street, is a Federal-style townhouse built between 1815 and 1816 by Thomas Lawrason. Following Lawrason’s death in 1819, his widow Elizabeth Lawrason continued to reside there with their five children and retained ownership until 1835. Because of its size and prominence, the house was selected by the city as the official residence for the Marquis de Lafayette during his visit to Alexandria on October 16, 1824, while Elizabeth Lawrason lodged with nearby relatives. Lafayette was formally introduced to the citizens of Alexandria by Anthony Charles Cazenove from the raised steps of 601 Duke Street, just north of the Lawrason House, which provided an elevated platform for public address. In appreciation for the use of her home, the City of Alexandria presented Elizabeth Lawrason with a silver goblet. Elizabeth Lawrason was the sister of Dr. James Carson, whose role in the Cazenove controversy is discussed elsewhere in this article. This account is drawn primarily from Marquis de Lafayette Returns: A Tour of America’s National Capital Region by Elizabeth Reese (History Press, 2024), pp. 63–68. ↩︎ - Elizabeth Lawrason — Burial Clarification

Although Elizabeth Lawrason is sometimes listed in secondary sources, including Find A Grave, as being buried in Christ Church Cemetery, the stone associated with her name there appears to be a cenotaph rather than a grave marker. Contemporary evidence indicates that Elizabeth Lawrason left Alexandria later in life to join her youngest son, George, in New Orleans, where she died on April 14, 1851. Wesley E. Pippenger notes her death in New Orleans in Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia, Volume 3. Additional documentation and family material provided by descendant Claire Bennett corroborate this account. Elizabeth Lawrason’s burial place in New Orleans was located in a low-lying cemetery that has since been lost to erosion as the Mississippi River altered its course, a fate shared by many early burial grounds in the region. ↩︎ - Even before Gordon’s squadron arrived, Alexandria had sought terms. On August 25, 1814, as a violent storm struck Washington during its burning, a delegation from Alexandria fought their way through the tempest to meet with Rear Admiral George Cockburn. Led by the Reverend James Muir of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House, the group included the Reverend William Holland Wilmer and Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick—a physician who had attended George Washington at his death in 1799. Cockburn, caught off guard, improvised assurances that if Alexandria offered no resistance, persons and property would be safe and the British would pay for whatever they took. The delegation bowed and returned into the storm. Today, Dr. Dick lies buried in the Quaker Cemetery beneath the Kate Waller Barrett Library—the very building where Catherine Weinraub discovered the Cazenove letter 211 years later. Muir rests thirteen feet beneath the floorboards of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House, where Cazenove would serve as Ruling Elder for 36 years. Wilmer died in 1827 and is memorialized by a tablet in Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, Virginia. See Walter Lord, The Dawn’s Early Light (1972), p. 182. ↩︎

- Captain James Alexander Gordon

Captain James Alexander Gordon (1782–1869) was one of the most experienced Royal Navy officers assigned to Chesapeake operations during the War of 1812. In 1814, the veteran officer—wounded earlier in the Napoleonic Wars and having lost a leg—commanded a squadron of frigates, bomb vessels, and a rocket ship during the arduous British expedition up the Potomac River toward Washington, D.C. Gordon later commanded the same vessels during the bombardment of Fort McHenry at Baltimore. Having gone to sea at age eleven, he served aboard at least nine vessels over two decades, earning a reputation as a model naval officer. Some historians have suggested that Gordon’s career may have influenced C. S. Forester’s fictional character Captain Horatio Hornblower. Following his active sea service, Gordon served for decades as superintendent of naval hospitals and dockyards and was ultimately promoted to Admiral of the Fleet. He was buried at Greenwich Hospital, remembered as the last surviving captain who had served under Lord Nelson. Ralph E. Eshelman and Burton K. Kummerow, In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake. ↩︎ - Edward Codrington

Edward Codrington (1770–1851) was a distinguished Royal Navy officer noted for his service at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) and as commander of the allied British, French, and Russian fleet at the Battle of Navarino (1827), the last major naval engagement fought entirely under sail. During the War of 1812, Codrington served as captain of the fleet to Sir Alexander Cochrane and participated in British operations in the Chesapeake and the attack on New Orleans. His victory at Navarino proved decisive in securing Greek independence, and he later received the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. The 1805 Club, Edward Codrington. ↩︎ - General John Mason

General John Mason (1766–1849) was a central figure in the War of 1812 and later American civic life. During the war, he served as Commissioner General of Prisoners and was responsible for sensitive diplomatic and military communications, including the handling of intercepted British correspondence. Mason later played a pivotal role in events leading to the creation of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” having formally dispatched Francis Scott Key on the mission that resulted in its composition. Mason is buried in Christ Church Cemetery in Alexandria. See also: David Heiby, “General John Mason: the Man Behind the Star-Spangled Banner and Other Remarkable Connections,” July 27, 2023. ↩︎ - Dr. James Carson

Dr. James Carson (1773–September 9, 1855), buried in Christ Church Cemetery within Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, was a physician, civic leader, and War of 1812 veteran who served as a first lieutenant in the Alexandria Artillery. During the war, he fought at the Battle of the White House under General Robert Young and later held multiple public offices, including customs officer, magistrate, superintendent of police, and inspector of the harbor. In October 1824, he commanded the civic escort for the Marquis de Lafayette during his visit to Alexandria and Washington’s tomb—an event that also involved Anthony Charles Cazenove and underscored the public reconciliation that followed the 1815 controversy. ↩︎ - Louis Cazenove

Louis Cazenove (1807–1852), eldest son of Anthony Charles Cazenove and older brother of William Gardner Cazenove, was a prominent Alexandria businessman and partner in Cazenove & Co., a major flour-exporting firm. In 1850, as a wedding gift to his wife, Harriot E. Tuberville Stuart—great-granddaughter of Declaration signer Richard Henry Lee—Louis purchased the Lee-Fendall House Museum, where the family undertook substantial renovations. Louis Cazenove died of scarlet fever in 1852 and was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery. His widow later leased the property, which was converted into the Grosvenor Branch Hospital during the Civil War. It eventually became a museum in 1974. ↩︎