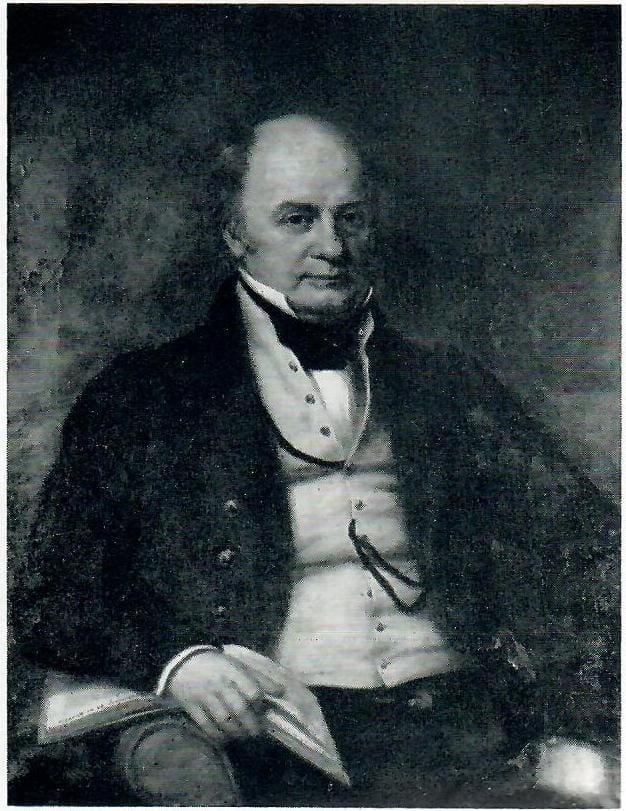

Introduction

General John Mason played a crucial role in the creation of the US National Anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” He sent Francis Scott Key on a mission during the War of 1812, where Key witnessed the British attack on Fort McHenry. Inspired by the flag still flying after the bombardment, Key wrote the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” later set to music as the national anthem. In 1931, it was officially adopted as such.

General John Mason’s Military Career

General John Mason’s military career was marked by notable achievements and responsibilities. From 1802 to 1811, he served as the first commanding General of the District of Columbia National Guard, then known as the District of Columbia Militia. His official rank during this period was Brigadier General. However, in 1811, Mason decided to resign, likely due to conflicts arising from his concurrent role as Superintendent of Indian Trade. Despite stepping down from his command, Mason’s dedication to service persisted. During the War of 1812, he assumed the crucial role of Commissioner General of Prisoners, demonstrating his ongoing commitment to the nation’s defense and the welfare of those under his charge.

On August 24, 1814, when the British took control of Washington, Mason courageously helped President Madison and other officials escape to Virginia and sent 120 British prisoners – many of whom claimed to be deserters to Frederick, Maryland.

General John Mason’s Contributions to the Development of Washington, D.C.

In addition to his role in creating the national anthem, General John Mason significantly contributed to the development of Washington, D.C. He established an office for his company, Fenwick, Mason & Company, in Georgetown 1792. The business thrived, and Mason soon owned a brick townhouse at the corner of 25th and L Streets, along with a warehouse, wharf, and several lots in what is now Southwest Washington.

Following his father’s death, George Mason, on October 7, 1792, John Mason inherited a significant portion of land along the Virginia shore of the Potomac River, opposite Georgetown, in present-day Arlington. As George Mason’s will outlined, the inherited property consisted of approximately 2,000 acres between Four Mile Run and the Lower Falls of the Potomac River in Fairfax County. Additionally, John Mason was bequeathed an island in the Potomac River known as Barbadoes or Analostan, opposite the mouth of Rock Creek. This island, also called Mason’s Island, is now known as Theodore Roosevelt Island, a park administered by The National Park Service. Although the island was undeveloped then, John Mason quickly began constructing a country home on the property, further expanding his influence and land holdings in the region.

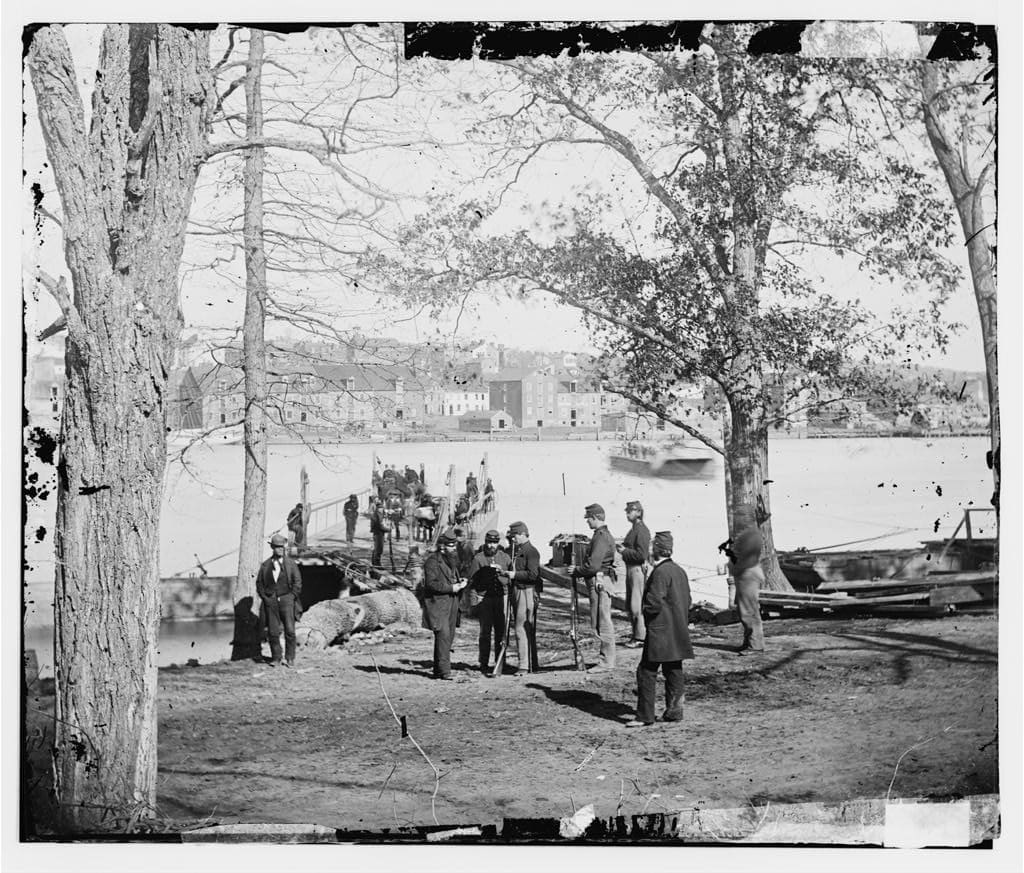

General John Mason’s Ferry and Its Historical Significance

Mason operated a ferry service that crossed the Potomac River from his Virginia land to Georgetown, adjacent to Analostan Island. The ferry had been located at that site since 1748, and when John Mason inherited the property, it remained the only means of crossing the river near Georgetown for many years. The ferry played a significant role in the region’s history, even before John Mason’s ownership.

In 1755, General Edward Braddock used this ferry to transport his force of British Regulars and Virginia recruits from Alexandria, Virginia, across the Potomac River to Georgetown. From there, they marched towards Fort Duquesne, intending to capture it from the French. Tragically, Braddock’s expedition met with a disastrous end. On July 9, 1755, Braddock’s army was defeated by a combined French and Native American force at the Battle of the Monongahela, near present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. General Braddock was mortally wounded during the battle. George Washington, who served as Braddock’s aide-de-camp, played a crucial role in rallying the troops and preventing a complete rout.

The road built by the Mason family to connect to the ferry would eventually become part of US Route 1, an important transportation corridor. The ferry remained the only means of crossing the river near Georgetown until 1797, when a bridge was constructed upstream, just below Little Falls, at the present site of Chain Bridge.

General John Mason’s Influence in the Financial Sector

Mason’s influence extended to the financial sector. In 1793, he became an incorporator and director of the Bank of Columbia in Georgetown. The bank served as the financial agent for the commissioners of the newly formed District of Columbia. In 1798, Mason took over as the bank’s president, succeeding Benjamin Stoddert, appointed Secretary of the Navy.

General John Mason’s Marriage and Family

The Mason family had ties to various important figures and events in American history, with members buried in different cemeteries.

- John Mason Jr. (1797 – 1859): Buried in Christ Church.

- James Murray Mason (Nov 1798 – 28 Apr 1871): Buried in Christ Church. He wrote The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and was involved in The Trent Affiar, which nearly caused a war between Great Britain and the United States at the start of the American Civil War.

- Sarah Maria Mason (born September 11, 1800, died July 29, 1890): Married Samual Cooper and is buried at Christ Church. Samuel Cooper was the highest-ranking Confederate General during the Civil War.

- Virginia Mason (born on October 12, 1802, passed away on January 21, 1838): Initially buried in the burial ground of Georgetown Presbyterian Church, she was eventually relocated to Arlington National Cemetery.

- Murray Mason (Jan 4, 1808 – 11 Jan 1875): A Captain in the Confederate Navy, buried in Christ Church.

- Maynadier Mason (Jan 4, 1808 – Apr 1865): The burial place is unknown.

- Catherine Eilbeck Mason: The burial place is unknown.

- Eilbeck Mason: Buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

- Anna Maria Mason (born on February 26th, 1811, passed away on November 3rd, 1898), also known as “Nannie”: Married Sydney Smith Lee, the older brother of Robert E. Lee. Both of them are laid to rest at Christ Church.

- Joel Barlow Mason (June 9, 1813 – 1861): The burial place is unknown.

It is evident that the Mason family played significant roles in various aspects of American history, and their final resting places are scattered across different cemeteries, some of which are known, while others remain unknown.

General John Mason’s role in the creation of “The Star-Spangled Banner“

General John Mason also played a crucial role in the mission leading to the creation of the US National Anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Following the British invasion of Washington, D.C., on August 24, 1814, a severe storm, possibly a derecho, hit the city the next day. The storm caused significant damage, but it also extinguished the fires set by the British, ultimately saving Washington.

After the devastating storms wreaked havoc and claimed the lives of numerous soldiers, the British forces retreated to their ships in Benedict, Maryland. However, amid the chaos and destruction, some of the soldiers took advantage of the situation and started looting houses in the area.

However, they were fully aware of the risks confronting the British soldiers. Fearing retaliation, they strategically decided to safeguard themselves and the soldiers they had apprehended. They decided to transport the captured soldiers to a jail approximately nine miles away in Queen Anne’s County.

Unfortunately, the British authorities discovered what had transpired, and in retribution, they swiftly arrested Dr. William Beanes. He was subsequently imprisoned on the British flagship, the H.M.S. Tonnant.

Dr. Beanes had influential friends, including Richard West, who sought help from his brother-in-law, Francis Scott Key. Key requested permission from President James Madison to visit the British fleet under a flag of truce and negotiate Beanes’ release. General John Mason officially appointed Key to join John Skinner, the American prisoner-of-war agent, on the mission.

Key and Skinner set out on a small American boat and encountered the British fleet near the meeting point of the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay. The British commander, General Robert Ross, agreed to release Beanes after learning that the Americans were treating wounded British soldiers humanely. During their time with the British, Key and Skinner overheard the enemy’s plans to attack Baltimore as retribution for the actions of American Navy Captain David Porter during the Battle of the White House Landing.

While negotiating Beane’s release, Key and Skinner had a unique opportunity to witness crucial British preparations and movements that would prove vital in the upcoming Battle of Baltimore, with a particular focus on Fort McHenry.

To prevent them from revealing the British attack plans after Beanes was released by Ross, the three were held captive on a truce ship, which remained attached to a British vessel during the battle. Throughout September 13 to 14, Key was a firsthand observer of the relentless bombardment that Fort McHenry endured.

Despite the intense onslaught, when the smoke eventually cleared, Key was filled with awe as he beheld the American flag still proudly flying over the fort. This powerful and inspiring sight moved him deeply, prompting him to craft a poem, cleverly parodying the popular song “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

Titled “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” the poem swiftly gained popularity as it spread throughout Baltimore. Within just thirty days, its name was changed to “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and it became an adored and cherished patriotic anthem among the American people.

As the years passed, “The Star-Spangled Banner” continued to capture the hearts of the nation, growing in popularity until finally, in 1931, it was officially declared the national anthem of the United States, serving as a powerful symbol of the nation’s unwavering resilience and deep-rooted patriotism.

General John Mason’s Success as a Merchant

After the conclusion of the War of 1812, General John Mason pursued successful endeavors as a merchant and banker in the Washington, D.C. area. In 1815, he acquired a foundry in Georgetown and managed its operations until his passing. Additionally, Mason was appointed as a director of the Potomac Company, an organization involved in improving navigation on the Potomac River to facilitate commerce and transportation.

As he continued to play an active role in public life, in 1842, Mason was named a Vestryman at Christ Church, a position of importance within the church’s leadership and administration.

During the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to Alexandria on October 17, 1824, General Mason was one of the dignitaries who accompanied Lafayette on the steamship “Petersburg,” along with numerous other citizens of Alexandria, on its journey to visit Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon.

Mason’s family had a significant historical connection, and he demonstrated his appreciation for this heritage in 1844. He made a generous contribution to the State Library in Richmond, now known as the Library of Virginia, by donating the first copy of the Bill of Rights. This document was authored by his father, George Mason IV, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and an influential figure in the development of American constitutional principles.

Throughout his life, General John Mason made notable contributions to both the private sector and public service, leaving a lasting impact on commerce, governance, and historical preservation. His legacy endures through his involvement in various ventures and his dedication to preserving the historical artifacts of the nation’s founding era.

General John Mason’s Financial Difficulties and Later Life

As the years passed, the business success that had once accompanied John Mason in his younger years began to wane. Financial difficulties arose as he found himself overextended, struggling to maintain sufficient funds. The most significant setback occurred in 1833 when he lost his cherished Analostan Island and his extensive land holdings along the Potomac River in present-day Arlington, including the rights to the ferry. This devastating loss was the culmination of a series of unfortunate events that had begun eight years prior in 1825. During that time, Mason had suffered substantial losses due to land speculation, forcing him to secure notes on the island and Arlington properties to cover his mounting debts. When 1833 arrived, he found himself unable to meet the obligations of these notes, resulting in the Bank of the United States foreclosing on his properties.

In the wake of this financial turmoil, General John Mason sought refuge at Clermont, a farm he owned nestled in the serene Cameron Valley, west of Alexandria. He made this his home until his passing in 1849. However, the final years of his life were marked by health challenges, as he found himself disabled by a series of strokes that began in 1846. Despite these hardships, Mason remained resilient, facing each obstacle with the same determination that had characterized his earlier successes.

Clermont’s Fate After General John Mason’s Death

Following Mason’s death, the property of Clermont underwent a series of unfortunate events. The house was sold to French Forrest, a respected U.S. Navy officer. However, when the American Civil War broke out, Forrest decided to join the Confederate Navy, leaving the property behind.

As a result of Forrest’s absence and his failure to pay property taxes in person, the authorities confiscated the house. Subsequently, the building was repurposed and used as a hospital for Contrabands, which referred to escaped slaves and freed African Americans who sought refuge behind Union lines during the war.

During this time, smallpox posed a significant concern, and the house was used to treat those affected by the disease. Tragically, in 1865, while attempting to decontaminate the house by burning beds and furniture, a fire broke out, leading to its destruction.

The grand residence of General John Mason at Clermont suffered an unfortunate fate, being destroyed by fire and lost to history. However, its significance lies in its association with Mason, a notable figure who played essential roles in the early history of the United States and the War of 1812. Despite the house’s destruction, his contributions to the nation’s history endure. Today, a Fairfax County elementary school bearing the same name stands near the site of the original house.

General John Mason’s Death and Legacy

General John Mason passed away in 1849 and was laid to rest in the family plot located in Christ Church Cemetery. The cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia, served as the final resting place for the Mason family members, including General Mason himself. Here, surrounded by his family’s memory, General Mason found his eternal rest, leaving behind a legacy that would be remembered for his contributions to the early history of the United States and his crucial role in the events leading to the creation of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

| JOHN MASON of Clermont, Fairfax County Virginia born April 4, 1766 died March 19, 1849 | ANNA MARIA MASON wife of JOHN MASON of Clermont, Virginia born Oct. 13, 1776 Died Nov. 29, 1857 |

Conclusion

General John Mason’s life was a tapestry woven with threads of military service, entrepreneurship, and pivotal moments in American history. From his role as the first commanding General of the District of Columbia National Guard to his crucial involvement in the events leading to the creation of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Mason left an indelible mark on the nation’s story. His contributions to the development of Washington, D.C., his influence in the financial sector, and his family’s ties to significant figures and events further underscore his importance. Despite the financial challenges he faced in his later years and the unfortunate fate of his beloved Clermont, Mason’s legacy endures through his enduring contributions to American history. As we reflect on his life, we are reminded of the courage, determination, and patriotism that shaped the United States in its early years, and we honor the memory of a man who played a vital role in that story. General John Mason’s final resting place in Christ Church Cemetery serves as a testament to his lasting impact, forever etched in the annals of American history.

This blog was updated on July 6, 2024, with additional information about Mason’s Ferry.

Sources of Information

Arlington Historical Society. (1976). The Mason Family of Mason’s Island. https://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/1976-5-Mason.pdf

Colonial Music Institute. (2022). George Washington’s Mount Vernon acquires the Colonial Music Institute. Retrieved from [Colonial Music Institute]

Fairfax County Schools. (2022). Clermont Elementary School. Retrieved from [link]

HistoryNet. (2022, August). David Porter. Retrieved from [historynet.com]

Johnston, J. H. (2012). From slave ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the history of an African American family.Fordham University Press.

Lord, W. (1972). The Dawn’s Early Light. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

National Weather Service. (2022, August). August 25, 1814 tornado. Retrieved from [National Weather Service]

O’Neill, P. L. (2014). “To annoy or destroy the enemy”: The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington. Burke, VA.

Pippenger, W. E. (1992). Tombstone inscriptions of Alexandria, VA (Volume 3). Family Line Publications.

The Alexandria Association. (1956). Our town 1749 – 1865. The Dietz Printing Company.

Vogel, S. (2013). Through the perilous fight. Random House, LLC.

Ward, R. D. (1881). General Lafayette in Virginia in 1824 and 1825: An account of his triumphant progress through the state. Richmond, VA.