Lee-Fendall House Associated Burials

Explore the final resting places of families connected to Alexandria’s historic Lee-Fendall House Museum

History of the Lee-Fendall House

This comprehensive interactive map shows the final resting places of individuals and families connected to the Lee-Fendall House Museum. View more than 16 individuals and families across six historic cemeteries and four Alexandria landmarks, linking the house to broader regional history.

Built in 1785 by Philip Richard Fendall on land purchased from his cousin Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, the Lee-Fendall House served as home to generations of notable Alexandrians—including at least 37 members of the extended Lee family, among them descendants of the Cazenove and Fleming lines. After remaining in Lee-family ownership for 118 years, it left the family in 1903, when it was purchased by Robert Forsythe Downham. In 1937, it was purchased by labor leader John L. Lewis from Downham.

George Washington was a frequent visitor to the Fendall household; his diary references Philip Richard Fendall more than seventeen times, underscoring their close personal and civic relationship. Following Washington’s death on December 14, 1799, the house became a gathering place where Alexandrians organized their participation in his funeral, held at Mount Vernon on December 18, 1799. During the Civil War, the house was seized for use as a Union hospital, where approximately 1,700 Union soldiers were treated.

1780s–1820s: Fendall Era

Philip Richard Fendall, Sr. purchased a half-acre lot at the southeast corner of Washington and Oronoco Streets in December 1784 for £300 and built the house the following year. Born in 1734 in Charles County, Maryland, and connected to the Maryland branch of the Lee family, Fendall began his career as a planter and colonial official, serving as clerk of the Charles County Court and attending provincial conventions in Annapolis in 1774 and 1775 as relations with Great Britain collapsed.

During the Revolutionary War, Fendall spent extended periods in Europe with his cousin Arthur Lee, who represented the Continental Congress abroad and assisted Benjamin Franklin in securing the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France. Returning to America in 1780, Fendall married Elizabeth Steptoe Lee, widow of Philip Ludwell Lee of Stratford Hall.

After independence, Fendall abandoned plantation life and relocated to Alexandria, reinventing himself as a merchant, banker, and investor. Elizabeth Steptoe Lee died in this house in 1789. In 1791, Fendall remarried within the extended Lee family, taking Mary “Mollie” Lee as his third wife. Their son, Philip Richard Fendall II, a prominent national figure, was born in the house in 1794.

From this home, the Fendalls hosted George Washington and played a prominent role in Alexandria society until Philip’s death in 1805. Mollie Fendall retained ownership of the house until her death in 1827, though she moved to Washington around 1825. Philip Richard Fendall II is buried in Alexandria’s Presbyterian Cemetery, while Philip, Elizabeth, and Mollie were later reinterred together at Ivy Hill Cemetery.

1828–1850: Edmund J. Lee Era

Edmund Jennings Lee acquired the house at auction in 1828 to settle the debts of his sister, Mary “Mollie” Lee Fendall. Continuing financial pressures forced a sale in 1834, though Lee’s son regained the property two years later. Edmund Jennings Lee repurchased the house in 1839 and lived there until his death in 1843. Ownership then passed to his daughters, Sally Lee and Harriet (Harriotte) Stewart, who did not reside in the house but retained it as a rental property until its sale to Louis Albert Cazenove in 1850.

Like earlier occupants, the Lee family relied on enslaved labor. The house’s original telescopic design included a one-story “servants’ hall,” reflecting common urban practices in which enslaved people lived and worked in spaces connected to, but separate from, the main dwelling. Others likely slept in work areas such as kitchens, pantries, stables, or rear outbuildings.

Tax and census records show fluctuating numbers of enslaved people associated with the household over time. A deed record from 1823 identifies six individuals held by Mary Fendall, though little is known about their later lives. As debts mounted, enslaved people were used as collateral by both Mary Fendall and her brother Edmund Lee, placing families at risk of separation through sale or transfer.

Edmund Jennings Lee, his wife Sarah Lee, and several descendants are buried in Christ Church Cemetery, including Ann Harriotte Lee Lloyd, Sarah “Sally” Elizabeth Lee Bland, Rev. William Fitzhugh Lee, and Cassius Francis Lee. Sarah Lee was the daughter of Richard Henry Lee, author of the June 1776 Lee Resolution calling for American independence and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

1850–1870: Cazenove Family

Louis Cazenove, Sr. purchased the house as a wedding gift for his second wife, Harriet Tuberville Stuart, granddaughter of Declaration of Independence signer Richard Henry Lee, and added Greek Revival features to modernize the property. His first wife, Frances Ansley, whom he married in 1837, died in 1847 at the age of 27, leaving three children—Frances Ansley “Fanny,” Charlotte Louise, and Eleuthera DuPoint. Frances, Charlotte, and Eleuthera are buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery, while Fanny is buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester.

Tragically, Louis Sr. died of scarlet fever in March 1852, followed later that year by his father, A.C. (Anthony-Charles) Cazenove, who also lived in the house. A.C., Louis Sr., and Harriet are all buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery. In 1853, Harriet changed her son’s name from Charles S. Cazenove to Louis Albert Cazenove—thereafter known as Louis Jr.—in honor of her late husband.

Harriet later purchased an eight-acre parcel on Seminary Hill, where she built a dwelling called Stuartland and relocated there. She leased the Lee-Fendall House until Union troops seized the property in 1863 for use as a military hospital. After the Civil War, the property was returned to Harriet, who sold it in 1870.

Louis Sr.’s granddaughter, Anna Eliza Gardner, married Cassius Lee, son of Edmund Jennings Lee. She is buried with her husband in Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery.

1870–1902: Fleming Era

Dr. Robert Fleming Fleming and Mary E. Lee Fleming purchased the home in 1870. Dr. Fleming, who suffered from tuberculosis, died on August 19, 1871 at age 54. Mary Lee Fleming remained in the house until 1879 and in 1872 expanded the property through the purchase of an additional one-acre parcel extending east to St. Asaph Street, before moving to Washington, D.C. Family accounts indicate that she later loaned the house to her sister, Myra Gaines Lee Civalier, and other relatives, including her brother Robert Fleming Lee, who occupied the property until its sale following Mary’s death on April 20, 1902. Dr. Fleming and Mary Lee Fleming are buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

While living at the Lee-Fendall House, Mary Fleming also expanded the family’s presence beyond Alexandria. In 1877, she purchased Green Mont, a farm near The Plains, Virginia, for her eldest son, Richard Bland Lee Fleming—a property still owned by her descendants.

The family later suffered a devastating loss. Richard Bland Lee Fleming’s younger brother, Thomas Fleming, along with Thomas’s son John Paton Fleming and daughter Mary Lee Fleming, were killed in the Knickerbocker Theatre disaster on January 28, 1922, when the theater roof collapsed during a blizzard.

All three are buried in Alexandria’s Presbyterian Cemetery, where the Fleming family plot lies near that of the Cazenove family—former owners of the Lee-Fendall House.

1903–1937: Downham Era

Robert Forsythe Downham (1876–1956) purchased the Lee-Fendall House at the southeast corner of Washington and Oronoco Streets from the heirs of Mary Fleming on October 30, 1903, for $5,500. He was the son of Emanuel Ethelbert Downham, who arrived in Alexandria from Bridgeport, New Jersey, in 1862 at the age of twenty-three and built a successful business in liquor distribution. E. E. Downham served two terms on Alexandria’s Common Council beginning in 1874 and became mayor in 1887. He married Sarah Miranda Price, daughter of Alexandria merchant George Price, and together they raised five children.

Robert, the fourth son, joined the family business along with his brother Henry. By at least 1876—the year Robert was born—the Downhams lived at 411 North Washington Street, a brick duplex in the same block as the Lee-Fendall House. Robert later established himself as a prominent Alexandria businessman, operating ventures in liquor sales, groceries, clothing, and real estate as the city entered the twentieth century.

The purchase of the Lee-Fendall House was encouraged by Myra Civalier II, daughter of Mary Lee Fleming’s sister Myra, who urged Mary Regina Greenwell—known as “Mai”—to acquire the property. Robert offered to purchase the house if Mai would marry him. A trained voice teacher, Mai performed in operettas along the East Coast before settling into life in Alexandria.

After acquiring the property, the Downhams undertook significant modernizing alterations. Rectangular shingles were applied to the exterior, bathrooms were installed in the main block for the first time, and a second-floor bathroom required replacing an east-wall window with a double window to provide light to both the bath and adjoining bedroom. The original heating system was also replaced with an oil furnace, resulting in the radiators still in use today.

Around 1931, Robert and Mai Downham moved to a smaller, newly built house at the corner of Oronoco and St. Asaph Streets and thereafter leased 614 Oronoco to other occupants.

The Downham family’s legacy is reflected in Alexandria’s burial landscape. Emanuel Ethelbert Downham and his wife, Sarah Miranda Price Downham, are buried in Alexandria’s Presbyterian Cemetery, among many of the city’s civic and religious leaders. Their son Robert and his wife are buried at Ivy Hill Cemetery. Together, these burial sites mirror the family’s multigenerational role in Alexandria’s political, commercial, and civic life.

1937–1972: Lewis Era

In 1937, Myrta Lewis purchased the house for $27,000 from her neighbor Mai Downham after expressing her admiration for the property through their mutual friend, Mrs. R. R. Sayers of 607 Oronoco Street. Myrta and her husband, John L. Lewis, moved into the house at a moment when Lewis stood at the height of his national influence as a labor leader.

John L. Lewis became president of the United Mine Workers of America in January 1921 and held that position for nearly four decades. Originally from Iowa, he had worked as a coal miner before rising through union leadership. During the 1920s and the Great Depression, Lewis played a central role in reshaping American labor policy, trading declining membership in the coal industry for higher wages and improved conditions. He and his advisor, W. Jett Lauck, helped secure key labor protections in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, including the right to unionize and bargain collectively—provisions later incorporated into the Wagner Act of 1935.

As federal labor policy expanded during the New Deal, the United Mine Workers relocated its headquarters to Washington, D.C., in 1934. Lewis operated for nearly twenty-five years from the former University Club near McPherson Square, positioning himself at the center of national political life. Around the time the Lewises purchased the Lee-Fendall House, Lewis helped launch the Committee for Industrial Organization (later the Congress of Industrial Organizations), which sought to unionize mass-production industries such as steel and automobile manufacturing and fundamentally altered the structure of American labor.

Myrta Lewis died in 1942 after a prolonged illness. A former schoolteacher, she was credited with encouraging her husband’s interest in literature and refining his oratorical style. Their daughter Kathryn, who had previously served as an officer in a UMW district, became Lewis’s personal secretary and remained so until her death in 1962. Although the Lewises entertained selectively, John Lewis maintained a firm separation between his public role and private life.

John L. Lewis died in the house on June 11, 1969, at the age of eighty-nine. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964 in recognition of his transformative impact on American labor. He is buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois, the same cemetery where Abraham Lincoln is interred. With the passing of John L. Lewis, the Lee-Fendall House once again stood at a crossroads—its story shifting from national influence back to the long arc of family legacy and preservation.

The Fendall Legacy Continues

A family connection spanning centuries – William Gray “Bill” Fendall maintained a lifelong connection to the Lee-Fendall House as a descendant of John Fendall, the older brother of Philip Richard Fendall, who built the house in the 1780s. After the death of John L. Lewis in 1969, Bill and his wife Bette considered purchasing the property themselves, reflecting the family’s enduring attachment to the house.

Although they did not acquire the property, Bill Fendall remained a devoted supporter of the Lee-Fendall House throughout his life. Upon his death in 2014, he designated the house as the sole beneficiary of his estate, establishing the Bill Fendall Trust as an endowment to support the museum’s long-term preservation and operations.

Bill Fendall was a veteran of both World War II and the Korean War and was awarded the Purple Heart for his service. He is buried with his wife Bette at Arlington National Cemetery. Through his bequest, the Fendall family’s connection to the house—spanning from its construction through its modern stewardship—continues into the present.

1972–Present: Museum Era

Preserving the legacy for future generations. Jay Winston Johns, Jr. founded the Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation on July 14, 1968, at the urging of Frances Shively, then a docent at the Robert E. Lee Boyhood Home. The Trust was created with the specific goal of acquiring and preserving the Lee-Fendall House following the death of John L. Lewis.

Johns was a Virginia preservation leader who also owned and preserved Highland, the Albemarle County home of President James Monroe, later donating the property to William & Mary.

The property was purchased through a collaborative funding effort that included $75,000 from the Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation, $65,000 from the Commonwealth of Virginia, and $35,000 from the City of Alexandria. After restoration and planning, the house opened to the public as a museum in 1974.

Frances Shively served as the museum’s first director and lived on the second floor, occupying rooms that had previously been used as John L. Lewis’s office. Operating as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, the Trust preserves the house’s architectural fabric and historical legacy for public benefit.

The Lee-Fendall House is listed on both the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register, recognizing its national, state, and local significance.

Civil War Hospital (1863-1865)

During the Civil War, the Lee-Fendall House was requisitioned as a branch of Grosvenor Military Hospital. Nearly 100 Union soldiers died in the house, and many were buried at Alexandria National Cemetery—the first government cemetery established during the Civil War in July 1862—located within the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex. The home witnessed the first recorded successful US Army blood transfusion and served as quarters for Chief Surgeon Dr. Edwin Bentley.

In May 1864, when officials proposed ending burials at Alexandria National Cemetery in favor of the newly established Arlington National Cemetery, Bentley objected, citing “great inconvenience and expense” and arguing that distance would “prevent the attendance of escort or chaplain and also the military burial to which every soldier is entitled.” His advocacy kept Alexandria National Cemetery active, with burials actually increasing in 1864–1865.

After the war, Bentley continued his Army career, co-founded Arkansas’s first medical school, and pioneered treatment for what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. When he died in 1917, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery—the very cemetery whose expansion he had once questioned in favor of Alexandria’s sacred ground.

How to Use This Interactive Map of Lee-Fendall House Burials

Click any marker to learn about each person’s life, read their full biography, and discover where they’re buried. Each story connects to the larger narrative of American history and the Lee-Fendall House legacy.

Historic Landmarks

Hover or click any landmark marker to learn about each historic site

Gold marker (H): Lee-Fendall House Museum

Red markers (R): Lee family homes

Purple marker (J): Jennings House

Red cross (✚): Civil War hospital sites

Family Cemetery Connections

Red markers (L): Lee Family burials and descendants

Brown markers (F): Fendall Family graves

Blue markers (C): Cazenove Family sites

Green markers (M): Fleming Family locations

Orange markers (D): Downham Family burials

Orange markers (S): Union soldiers who died in the house

Dark Gray markers (B): Modern family supporters

Interactive Features

Click “Read Full Biography” to explore their complete story

Click “Visit Museum Website” to plan your visit to the Lee-Fendall House

Click “View Cemetery” to see their burial location and other notable burials there

Planning a visit? Both markers and popups provide addresses and directions

Historic Locations

Cemetery Connections

Stories Spanning Six Historic Cemeteries

From Christ Church Cemetery to Arlington National Cemetery, discover the interconnected stories of those who lived, worked, and died in the Lee-Fendall House:

Founding Families

The Lees and Fendalls who built Alexandria society, hosted George Washington, and shaped the early Republic through politics, law, and commerce.

Civil War Hospital

Union soldiers who died in the Lee-Fendall House hospital, plus the physicians like Dr. Edwin Bentley who performed groundbreaking medical procedures.

Merchant Families

The Cazenoves, Flemings, and Downhams who modernized the house and connected Alexandria to national and international commerce networks.

Historic Preservation

Those who worked to protect the Lee-Fendall House and preserve its historical and architectural legacy for public understanding.

Plan Your Lee-Fendall House Exploration

Start at the Museum: Visit the Lee-Fendall House Museum at 614 Oronoco Street to see where these families lived

Explore the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex: Many Lee-Fendall House families rest within this historic cemetery complex, including Presbyterian Cemetery (1809) and Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery (1808), along with Alexandria National Cemetery (1862) where Union soldiers who died in the house are buried—making it an ideal central stop for your cemetery tour

Venture Beyond: Use this map to discover notable figures at Ivy Hill Cemetery (1856), St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery (1796, end of S. Royal Street), and Arlington National Cemetery (1864)

Interactive Features: This map provides addresses and directions to help you explore Alexandria’s historic sites and plan an efficient route through multiple cemetery locations

These remarkable individuals represent the diverse families and visitors who called the Lee-Fendall House home across nearly two centuries. Each grave tells a story that connects to the broader narrative of American history—with many of these stories concentrated within walking distance of each other in Alexandria’s historic Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Research Sources

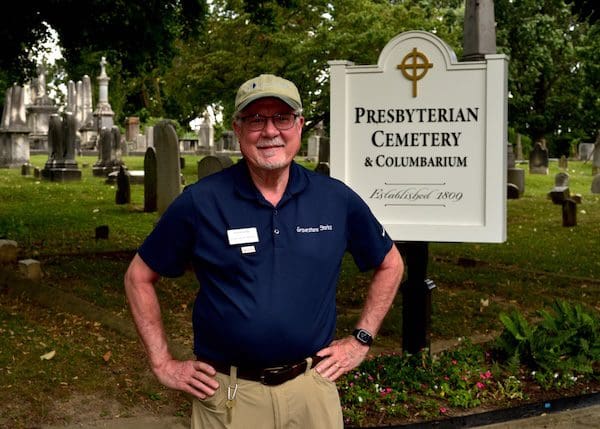

This interactive map combines original research from Gravestone Stories with additional historical documentation:

Smith Group. (2023, June 30). Lee-Fendall House historic structure report: 614 Oronoco Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22314 (Final report). Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation.

Gravestone Stories biographical research and cemetery documentation.

Primary source materials provided by Fleming family descendants.

Explore More Interactive Maps on Alexandria’s Hidden History

In addition to the Lee-Fendall House map, Gravestone Stories offers several other interactive resources that bring Alexandria’s layered past to life:

Discover 50 Extraordinary Lives Buried in Alexandria

From George Washington’s lost pallbearer to Cold War spies—explore the remarkable individuals who shaped American history and now rest in Alexandria’s cemeteries. Each pin reveals a story of triumph, tragedy, and transformation.

Alexandria’s African American Heritage

A starting point for discovering Alexandria’s rich African American heritage. Explore historic cemeteries, churches, civil rights landmarks, and the stories of educators, leaders, and community builders who shaped the city.

Interactive Map of Fallen Firefighters in Alexandria

Honoring the brave firefighters and leaders who served Alexandria from 1774 to today. Discover their heroic stories and final resting places throughout the city’s historic cemeteries, including the tragic 1855 Dowell China Shop Fire.

Alexandria Cemetery Map

Use our comprehensive cemetery map to discover the locations of 34 significant historic burial grounds throughout the city. This interactive guide leads you to Revolutionary War patriots, Civil War heroes, lost family cemeteries, and more than 260 years of American history.

Last updated: December 30, 2025