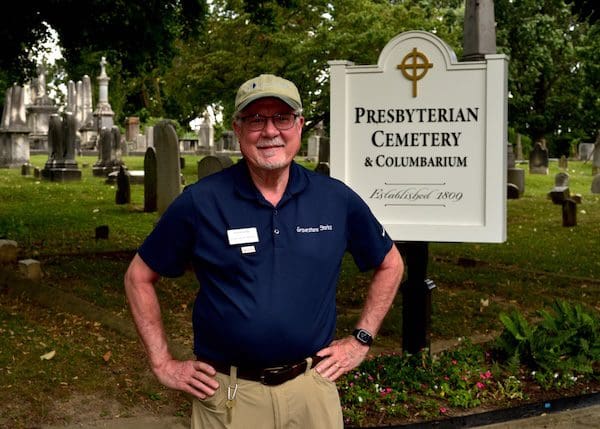

A directory of individuals interred in the historic Trinity United Methodist Church Cemetery, established in 1808 in Alexandria, Virginia, is provided below. Please note that this list is not exhaustive and will be updated periodically. If you know a notable story or individual that should be included, we invite you to contact Gravestone Stories.

Trinity United Methodist Church, initially known as the Methodist Episcopal Church, was founded on November 20, 1774. The inaugural Meeting House 1 was constructed in 1791, located on Chapel Alley near Duke Street and just north of Fairfax Street. In 1803, a new church building was erected on the eastern side of the 100 block of South Washington Street. By 1810, the original property was sold to what is now recognized as The Basilica of St. Mary, formerly St. Mary’s Catholic Church. In 1941, Trinity moved to its present location at 2911 Cameron Mills Road.

On December 15, 1808, congregation members purchased the land now occupied by the cemetery for $340.00. This cemetery is home to the graves of more than 550 people, including eight veterans of the Revolutionary War, one veteran of the War of 1812, a former Mayor of Alexandria, early pioneers from the free Black community, and numerous other former residents of Alexandria.

A

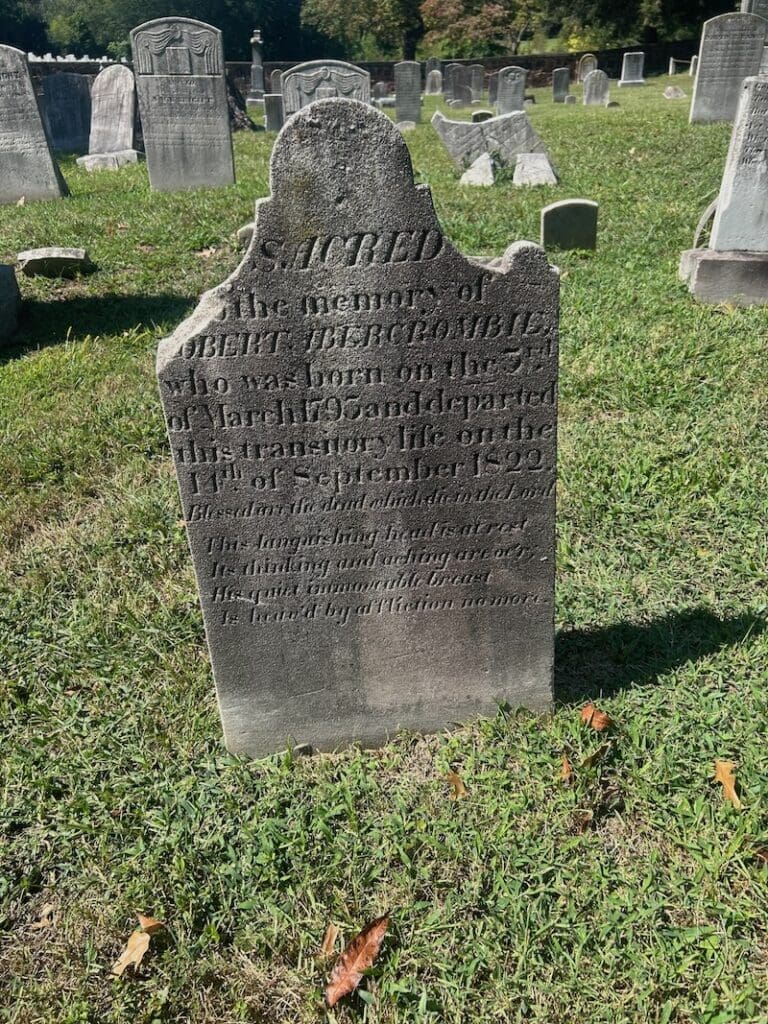

Robert Abercrombie: Alexandria Cabinet Maker and War of 1812 Veteran

Early Life and Military Service Robert Abercrombie was a furniture maker and War of 1812 veteran who became a prominent figure in Alexandria’s thriving furniture industry. After losing his father in 1810, he served as a Private in the 1st Regiment DC Militia during the War of 1812.

Business and Marriage He married Susan Wood in 1820 and established a successful cabinet warehouse in Alexandria, becoming known as both a furniture maker and importer. Operating between 1820-1860 in Alexandria’s furniture district along King Street, Abercrombie followed the traditional craftsman approach to hand-crafted, fine furniture using traditional methods, alongside other notable makers like Charles Koones, James Green, and William H. Muir.

Legacy and Recognition His contributions to the city’s furniture trade were significant enough to earn recognition on a historical marker in Alexandria’s Furniture District at King and Columbus streets.

Family Connections The family continued in Alexandria, with his daughter Martha marrying James W. Lugenbeel in 1846. Lugenbeel became a distinguished physician and humanitarian who served as colonial physician for Liberia and chronicled the country’s constitutional convention in 1847, dying in 1857. Martha later died in New York City in 1877 and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, while both her father and husband are buried in Trinity Cemetery.

F

Abraham Faw (1747–1828): Maryland Ratifier of the U.S. Constitution and Alexandria Civic Leader

Born in Benken, Switzerland, Abraham Faw (originally Pfauw) immigrated to Maryland with his family and became a successful merchant in Frederick Town. During the Revolutionary War, he supported the American cause by supplying cloth for military uniforms and helping construct a powder magazine and barracks to house British prisoners captured at Saratoga and Yorktown. He served on Frederick’s Committee of Observation beginning in 1775 and later represented the county in the Maryland House of Representatives (1786–1788), where he supported efforts to abolish slavery. In 1788, Faw served as a delegate to Maryland’s Ratification Convention and signed the U.S. Constitution.

After the war, he relocated to Alexandria, Virginia, where he became an active member of the Presbyterian Meeting House and served the city as a justice of the peace, Hustings Court justice, coroner, and alderman.

Faw married three times. His first wife, Julianna Boyer Lowe, bore him one son. His second wife, Mary Ann (Mary Anne) Steiner Faw, with whom he had three children, died in January 1805 and was buried in the burial ground of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House on January 20 of that year. Contemporary research indicates that she died alone and likely took her own life—an event that would have carried profound social and religious stigma in the early republic. Faw married his third wife, Sarah Moody, in Alexandria in 1808. Sarah Faw (1764–1818) is buried beside him in Trinity Methodist Cemetery.

H

John Wesley Hollensbury (July 11, 1803 – November 8, 1876): The Man Behind Alexandria’s Iconic “Spite House”

John Wesley Hollensbury, the man behind Alexandria’s iconic “Spite House,” lies buried in Trinity Cemetery. A brickmaker and city council member of Alexandria, Virginia, Hollensbury resided in a Queen Street home built in 1780 adjacent to an alley. He purchased the alley lot at 523 Queen Street for $45.65 to prevent damage to his walls and reduce noise. In 1830, he erected the Spite House, a 7 feet 6 inches wide and 25 feet deep structure. Despite its modest size of 350 square feet, the Hollensbury Spite House has garnered international attention, even appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Its distinctive design, featuring a slim front door and petite furniture, has transformed it into a tourist attraction. While it’s widely accepted that Hollensbury built the house out of spite, alternate theories suggest neighborly disputes or perhaps a gift for his daughters. The Spite House remains a celebrated local landmark regardless of its origins.

John Hollensbury and his two daughters, Francis “Fannie,” who succumbed to Tuberculosis, and Harriet, who passed away from Dropsy (an archaic term for edema or tissue swelling), rest in peace in A:5 of Trinity Cemetery. Another sister, Julia, is interred at the Washington Street United Methodist Cemetery (Union) at the end of Hamilton Avenue, within the complex.

Another sister, Charlotte Hollensberry Sherwood, is also buried in Trinity Cemetery. Her spouse, Joseph Thomas Sherwood, found his final resting place in The Presbyterian Cemetery.

| JOHN WESLEY HOLLENSBURY born Sept. 16, 1816 died Nov. 8. 1876. |

L

James W. Lugenbeel: The Man Who Documented Liberia’s Independence

James Washington Lugenbeel (1819–1857) served as colonial physician for Liberia and U.S. Government Agent for Recaptured Africans beginning in 1843. His most significant contribution to history came in July 1847, when he kept a detailed journal during Liberia’s constitutional convention—the only surviving eyewitness account of the proceedings that created Africa’s first independent republic.

Born in Virginia and educated at Columbian University (1841), Lugenbeel married Martha Alice Abercrombie in Alexandria in 1846. After his service in Liberia, he published Sketches of Liberia (1850), a comprehensive account of the young nation’s geography, climate, diseases, and indigenous customs that remains a valuable primary source for scholars today.

Lugenbeel served as Recording Secretary for the American Colonization Society at its 1852 annual meeting, a role recognizing his meticulous documentation skills. He died at just 38 years old on September 22, 1857.

His gravestone features a carved open book—a Victorian symbol of a life ended prematurely, with pages left unwritten. The symbolism is particularly poignant: he was a published author and chronicler whose “book of life” closed too early.

Read the complete story: The Man Who Documented Liberia’s Constitutional Convention

| JAMES W. LUGENBEEL died Sept 22nd 1857 Aged 38 Years But God will redeem my soul from the power of the grave: for he shall receive me. Psalm XLIX. XV. |

John Longden (1755–1830): Revolutionary War Veteran & Early Civic Leader

A veteran of the Revolutionary War, John Longden settled in Alexandria in 1783 and became an active civic leader. He served as keeper of the poorhouse from 1794 to 1796, a city councilman in 1797, clerk of the market from 1798 to 1799 and again from 1803 to 1805, and superintendent of police in 1808. From 1811 to 1823, he represented the Second Ward on Alexandria’s city council for most of that period.

In 1819, Longden built the Federal-style brick home at 1707 Duke Street, where he lived until his death in 1830. The property later passed to his grandson, Edgar L. Bentley, who sold it in 1844 to Joseph Bruin—a notorious slave trader who used the house as a slave jail in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Bruin is buried almost directly across Wilkes Street from Longden’s grave, in the Methodist Protestant Cemetery.

M

John A. Muir (December 6, 1807 – August 22, 1865): A legacy of Craftsmanship

John A. Muir (December 9, 1807 – August 22, 1865) served as the Mayor of Alexandria from 1853 to 1854. He hailed from a distinguished lineage of Muirs, many of whom found their final resting place in the nearby Presbyterian Cemetery. To read more, click here. Alongside his brother, James F. Muir, they continued the family’s proud furniture business tradition, a legacy prominently featured in the Alexandria Gazette in 1876.

The craftsmanship of the Muir family endures to this day, with valuable furniture pieces from John A. Muir’s workshop highly sought after. When they occasionally appear in the market, these pieces command substantial prices and are cherished by collectors and historians for their exceptional quality, aesthetic appeal, and historical significance.

The Muir family’s narrative took a dramatic turn during the Civil War, as they found themselves divided in their loyalties. While Stephen Shinn, who had wed Mary’s younger sister, sided with the North, James Green, Jane, and their children leaned towards the South. This familial schism was later depicted in the PBS miniseries ‘Mercy Street,’ set in the Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, providing a window into the complexities of that era.

Resting beside John A. Muir is his wife, Lydia Robinson, born in 1811, who passed away on April 29, 1853, at the age of 43, as indicated on her tombstone. Sadly, two children are also buried with the Muirs. Nannie Roszel, their daughter, died on June 5, 1854, and Eleanor Johnson, born on October 6, 1864, and died on July 10, 1865.

| In memory of JOHN MUIR Born December 9, 1807 Died August 22, 1865 ELEANOR JOHNSON Born October 6, 1864 Died July 10, 1865 | In Memory of LYDIA, consort of JOHN MUIR Mayor of Alex. who died April 29, 1853, aged 43 years. For 27 years a member of M.E. Church She could say as life ebbed space I would not live away No welcome the tomb. Since Jesus hath lain there I dread not his glory NANNIE ROSZEL daughter of J. & L. MUIR died June 5, 1854 |

S

John Sloan (1758–1815) Possible Revolutionary War Veteran

John Sloan was born on March 6, 1758, in British Colonial America. He lived through the upheaval of revolution and the birth of a new nation—and may well have helped secure its independence. Today, his grave stands in Alexandria’s Trinity United Methodist Church Cemetery, marked with a bronze medallion from the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), which formally recognizes him as a patriot in its national database (SAR Patriot #329188).

While no Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) record has yet been confirmed, strong circumstantial evidence suggests Sloan may be the same John Sloan who enlisted in the 8th Virginia Regiment during the Revolutionary War. According to historian Gabriel Neville’s research, featured on the 8th Virginia Regiment’s blog and its “The Soldiers” directory, a John Sloan enlisted in January 1777 for a one-year term in Captain George Slaughter’s Culpeper County company. This shorter-than-usual enlistment likely indicates he served as a substitute—completing another man’s obligation. A likely older brother, Bryant Sloan, enlisted in the same company a year earlier and later settled in Kentucky.

John Sloan appears to have followed a similar path. Records suggest he may have participated in the 1782 reprisal raid on New Chillicothe following the Battle of Blue Licks, one of the final frontier engagements of the war.

What makes his story unusual is that, unlike many veterans who moved westward after the Revolution, Sloan appears to have returned east, ultimately settling in Alexandria. He married Ann Rebecca Sloan, and they had a daughter, Mary, born late in their lives in 1804. Mary married Peyton Randolph and eventually moved west, helping to settle parts of Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois.

John died on February 26, 1815, and was buried in Alexandria. Ann passed away just seven months later and was laid to rest beside him. Sadly, her broken gravestone now rests behind her husband’s intact marker—a silent, poignant reminder of time’s erosion.

While definitive military records for John Sloan remain elusive, his grave—and the research surrounding it—stands as a potential link to the 8th Virginia Regiment and the Revolutionary generation.

Edgar Snowden, Sr. (December 21, 1810 – September 24, 1875) Owner and Publisher of the Alexandria Gazette

Edgar succeeded his father at 21 and assumed ownership and publishing responsibilities of the Alexandria Gazette. Between 1839 and 1843, he held the position of Mayor of Alexandria. After Alexandria’s retrocession to Virginia in 1847, he represented the city in the State Assembly.

He wed Lucy Grymes (March 30, 1814 – April 25, 1897), the great-niece of Lucy Grymes Lee (1734 – 1792). Lucy Grymes Lee, who lies to rest at Leesylvania Plantation Cemetery in Woodbridge, Virginia, was married to Henry Lee (1729 – October 1787) and interred at Leesylvania. They were the parents of Henry “Light House” Harry Lee III (January 29, 1756 – March 25, 1818), whose final resting place is the Lee Chapel Museum in Lexington, Virginia.

The Snowden family lived at 619 South Lee Street, often known as the Snowden House or Mansion, until 1912. 1937 Hugo L. Black (1886-1971) acquired the house. Black, a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937, later served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 until his passing in 1971.

Upon Edgar’s retirement, his son, Edgar Jr. Snowden (1833 – July 29, 1892), continued the family legacy by taking over the Gazette, holding the position until 1911. Edgar Jr. and several family members are interred at Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery.

Souces of Information

Dahmann, D. (2025). Account of the American Revolution and the transformation of Britain’s overseas colony of Virginia into the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States of America – Excerpt from the draft history of Alexandria’s Old Presbyterian Meeting House [Unpublished manuscript excerpt]. Provided by the author via personal communication.

Dahmann, D. C. (2022). The roster of historic congregational members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House[Unpublished manuscript]. Alexandria, VA.

Gibson, P. & Gibson, T. (2023, June). Personal communication on Snowden family memories and selected notes.

Kraus, A. (2010). Historical overview and assessment of the Bruin Slave Jail property (1707 Duke Street), City of Alexandria, Virginia. Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/sitereportkraus2010bruinslavejailax172.pdf

Lee, Jr., Cazenove Gardner. Lee Chronicle Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia. Published for The Society of the Lees of Virginia by Thomson-Shore. Dexter, Michigan. 1957.

Pippenger, Wesley E. Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volume 1, Family Line Publications, Westminster, MD, and Heritage Books, Inc., Bowie, MD. 1992.

Trinity United Methodist Church. (n.d.). Homepage. Trinity Alexandria. URL

- In colonial Virginia, the term Meeting House was commonly used to describe places of worship for non-Anglican congregations, including Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists. These dissenting religious groups were officially tolerated after 1776 but still faced legal restrictions under the Anglican establishment. For example, meeting houses were often required to keep their windows and doors closed during services—ostensibly to contain “blasphemous” teachings that challenged the Church of England’s authority. ↩︎