On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln held a New Year’s Day Reception at the White House. He shook so many hands of the dignitaries, officials, and members of the general public who attended that afterward, he was afraid his hands would shake when signing The Emancipation Proclamation later that day. The proclamation changed the course of the war by not only freeing slaves in the states still in rebellion against the north, but it also authorized arming and training regiments of “colored volunteers” to fight for the north.

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, ……… order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free…. [S]uch persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States….

The Proclamation freed approximately 3 million enslaved men, women, and children in the states still in rebellion.

“And we’ll stand by the Union if we only have a chance.”

An estimated 180,000 Freedmen and Contrabands, or fugitive slaves, answered Lincoln’s call. This amounted to one-tenth of those that fought for the North during the last two years of the war. The soldiers were organized into 175 regiments. Called the United States Colored Troops, or U.S.C.T., they made a mighty contribution to the Union’s victory in the American Civil War.

In Virginia, on May 15, 1863, the 23rd Regiment of the United State Colored Troops assisted the 2nd Ohio Cavalry during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. While a minor skirmish, their actions that day proved to many white soldiers that Blacks would fight when given the opportunity. U.S.C.T. soldiers also fought at Vicksburg, Petersburg, Richmond, Nashville, Fort Fisher, and Appomattox.

The Army of the James’s XXV (25th) Corps, which consisted of over 13,000 men, including infantry, cavalry, and artillery, was made up entirely of U.S.C.T. soldiers. As with every regiment, white officers led black enlisted soldiers. They fought in the Battle of Hatcher’s Run, were present at the fall of Petersburg, and helped during the pursuit of Lee’s army after the fall of Richmond, Virginia, sometimes marching thirty miles in one day. Two regiments of the XXV Crops also took part in the Battle of Clover Hill, the last battle between the Union and Confederate forces before Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, 1865. They were transferred to Texas in May, where they became the Army of Occupation. The XXV Corps was disbanded on January 8, 1866.

“Then here is to the 54th.”

The most famous U.S.C.T. regiment in the war was the 54th Massachusetts.

The fierce determination of the U.S.C.T. soldiers during the assault on Fort Wagoner convinced skeptics that armed African Americans could fight. Many members of the 54th received medals for their valor that day, including Sergeant William Carney, who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. All told, sixteen U.S.C.T. soldiers earned the Medal of Honor during the entire war.

“Ole Jeff says he’ll hang us if we dare to meet him armed“

The Confederacy’s reaction to arming colored men was harsh. They threatened to hang their white officers, sell into slavery any captured Black Union soldiers, and refused to treat them as prisoners of war.

In response, on July 31, 1863, Lincoln issued General Order 252, which stated: “It is therefore ordered that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery[,] a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works, and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war.” The order did not stop the Confederates from atrocities against armed African Americans.

On April 12, 1864, during the Battle of Fort Pillow in Tennessee, Confederates under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest slaughtered hundreds of U.S.C.T. soldiers who had surrendered during the fight. “The affair at Fort Pillow was simply an orgy of death, a mass lynching to satisfy the basest of conduct—intentional murder—for the vilest of reasons—racism and personal enmity.”

“About the courage of the colored volunteers.”

On July 30, 1864, the Battle of the Crater occurred during the siege of Petersburg. As at Fort Pillow, many U.S.C.T. soldiers were massacred after surrendering.

Union sappers, mostly Pennsylvania miners from the 48th PA, spent several weeks digging a mine shaft 510 feet long under a Confederate salient and packed it with over 8,000 pounds of gunpowder. Once the tunnel was finished, the power would be blown, and Union soldiers would rush through the gap and hopefully break the stalemate of months of trench warfare.

For two weeks, two divisions of U.S.C.T soldiers under the command of Brigadier General Edward Ferrero had trained to lead the Union assault once the mine blew. One division was tasked to go to the left of the crater and the other to the right, and by doing so, would bypass the hole altogether. They then were tasked with extending the breach perpendicular down the Confederate’s line on either side. This would allow subsequent follow-up soldiers to fan out beyond the breach and seize an important road 1600 yards beyond, and perhaps Petersburg.

However, despite careful planning, at the last moment, Major General George Meade ordered Major General Ambrose Burnside, the commander of the IX Corps, not to use U.S.C.T. soldiers as the lead assault troops. Burnside then selected Brigadier General James Ledlie’s First Division to lead the assault instead. The change doomed the operation.

When the mine exploded at 4:40 a.m. on the 30th, it blew a gap 130 long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep in the Confederate fortifications and immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers. After the dust settled, Ledlie’s troops moved into the crater instead of going around it as the U.S.C.T. soldiers had been trained because they thought it would make an excellent rifle pit to take cover. To make matters worse, their commanding officer did not brief them on what to expect, refused to lead them during the battle, stayed behind the lines, and got drunk.

Eventually, a few Union soldiers were able to break free and push back the Confederates, which allowed survivors inside the crater to retreat. After several hours of hand-to-hand combat, the Confederates were able to reclaim the earthworks and drive the Union troops away.

Union casualties were 3,798, including 504 killed, 1,881 wounded, and 1,413 missing or captured. The Confederates lost 1,491 men (361 killed, 727 wounded, 403 missing or captured). Most of the Union losses were suffered by Ferrero’s division of the United States Colored Troops, who were killed after they surrendered. Union Commander General Ulysses S. Grant wrote to Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck, “It was the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.”

Afterward, one Confederate soldier wrote back home that all the colored prisoners “would have been killed had it not been for gen Mahone who beg our men to Spare them.” One of his comrades killed several, he continued; Mahone “told him for God’s sake stop.” The man replied, “Well gen let me kill one more,” whereupon, according to the correspondent, “he deliberately took out his pocket knife and cut one’s throat.”

After the battle, a few wounded U.S.C.T. soldiers ended up in the L’Ouverture General Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. Those that died were eventually buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery. But their journey to their final resting place was not easy since, initially, they were buried in another Alexandria cemetery.

“We had a hard road to travel.”

In 1865, a petition was circulated and signed by 443 U.S.C.T. soldiers who were convalescing in the L’Ouverture Hospital. They objected to being called “Contrabands,” a term used to describe fugitive slaves who ran away from their enslavers during the war. The petition requested “…the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who differ only in color…” and that black soldiers who had died in Alexandria and buried in the Contraband and Freeman’s Cemetery located at 1001 S. Washington Street, be removed and be reburied next to their white brothers-in-arms in the Soldier’s Cemetery on Wilkes Street.

After receiving the petition, the United States Government ordered that 118 U. S. C. T. soldiers who previously were buried in the Contraband and Freedman’s Cemetery be disinterred and reburied in the Soldier’s Cemetery. Twenty-three signers of the petition later died and were buried in the Soldier’s Cemetery. After the war, the cemetery’s name was changed to Alexandria National Cemetery.

“As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free“

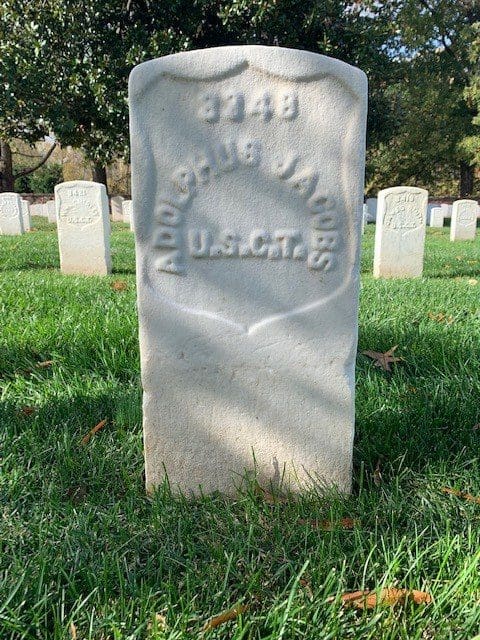

Among the 249 members of the U.S.C.T. soldiers buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery is Private Adolphus Jacobs of the 28th Infantry.

Private Jacobs never recovered and died on August 14, 1864, at 22, and was buried in the Contrabands and Freedmens Cemetery.

There are over 3500 Union soldiers, including 249 members of the United States Colored Troops, at rest in the cemetery, all heroes who truly died “to make man free!”

Give Us a Flag

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment sang this song. The 54th was the most famous regiment of the United States Colored Troops that fought in the war. The author of the song is unknown. You can read along while listening to this version by Richie Havens.

Oh, Frémont he told them when the war it first begun,

How to save the Union and the way it should be done.

But Kentucky swore so hard and Old Abe he had his fears,

Till ev’ry hope was lost but the colored volunteers.

CHORUS:

Oh, give us a flag,

All free without a slave;

We’ll fight to defend it as our fathers did so brave;

The gallant Comp’ny “A”,

Will make the rebels dance,

And we’ll stand by the Union if we only have a chance.

McClellan went to Richmond with two hundred thousand brave;

He said, “Keep back the niggers” and the Union he would save;

Little Mac he had his way, still the Union is in tears,

Now they call for the help of the colored volunteers.

CHORUS

Old Jeff says he’ll hang us if we dare to meet him armed,

A very big thing , but we are not at all alarmed;

For he first has got to catch us before the way is clear,

And that is “what’s the matter” with the colored volunteer.

CHORUS

So rally, boys, rally, let us never mind the past;

We had a hard road to travel, but our day is coming fast;

For God is for the right, and we have no need to fear,

The Union must be saved by the colored volunteer.

CHORUS

Then here is to the 54th, which has been nobly tried,

They were willing, they were ready, with their bayonets by their side,

Colonel Shaw led them on and he had no cause to fear,

About the courage of the colored volunteer.

CHORUS

Sources of Information

Wiley, Bell Irvin, (2008) [First published 1943]. The Life of Johnny Reb: the Common Soldier of the Confederacy. Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Miller, Edward A. Jr. Alexandria Historical Quarterly. Volunteers for Freedom: Black Soldiers in the Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II. The Office of History Alexandria. Published Winter 1998.

Pippenger, Wesley E. Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Volume 5. Heritage Books, Inc. Berwyn Heights, Maryland. 2014.

The official website of The Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, Alexandria, Virginia. First accessed 2019.

The official website of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, and an article about the Alexandria National Cemetery. Accessed July 2022.

Wikipedia article on the Battle of the Crater. Accessed October 2022.

Official website of the United States Army and Medal of Honor recipients. Accessed November 2022.