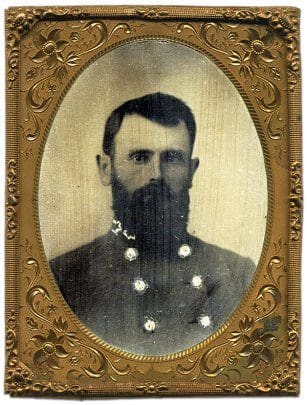

Buried in Alexandria, Virginia’s Presbyterian Cemetery, is Samuel Richard Johnston (March 16, 1833 – December 24, 1899), who some blame for Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg.

Born at West Grove

Johnston was born at West Grove, his family’s plantation south of Alexandria, now the Belle Haven Golf Course and Country Club site.

West Grove was constructed by Major John West in 1700. In 1730, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law named the Tobacco Inspection Act. This law required Virginians to construct warehouses on the waterfront for inspecting tobacco. Additionally, inspectors were appointed to examine the tobacco before it was shipped to England. One of the potential locations for a warehouse was John West’s property. However, the new site needed to be deeper, making it unsuitable for large boats. As a result, the assembly chose a 100-acre piece of land to the north. In 1749, this land became the establishment of Alexandria. The West family resided in West Grove for four generations. Further information about the West family can be found in this link: [18th Century Burials in Alexandria].

In 1815, the family sold the house and land to Dr. Augustine Smith (April 28, 1774 – March 12, 1830). He is buried in St. Paul’s Cemetery. In 1830, Dennis Johnston (1787 – July 22, 1852), buried in Section B, plot 192, in the Presbyterian Cemetery, bought West Grove. Dennis Johnston’s son, George Johnston (July 22, 1829 – July 17, 1897), who was also buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery, inherited the house in 1852. George was a high-ranking officer in the Quartermaster Department of the Confederacy and the older brother of Samuel Johnston.

In 1861, West Grove was burned down by a fire, most likely by the 39th New York soldiers who set up camp there at the start of the Civil War. They were aware of George Johnston’s involvement in the rebellion. The land where Fort Willard was situated during the Civil War belonged to Samuel Johnston. Fort Willard was one of the 68 forts built around Washington. It is located uphill from West Grove. Today, it has become a Fairfax County Park. You can find more information on this [website].

After the war, the Johnston family owned the land until 1924, when they sold it and transformed it into the Belle Haven Country Club.

July 2, 1863

Initially, Johnston was a lieutenant in Company F of the Sixth Virginia Cavalry. Later, he was assigned to J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry to work with the Engineer Corps. He excelled in reconnaissance work. After that, he joined Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s staff, the First Corps commander in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. In August 1862, he became a member of Lee’s staff and remained in that position throughout the war.

On July 2, 1863, during the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 – 3, 1863), he was woken up from sleep at 4:00 a.m. and sent to Lee’s headquarters near the Lutheran Seminary. Lee instructed him to “check out the enemy’s left side and let me know what you find as soon as you can.”

Johnston returned three hours later and informed Lee that he had arrived at “Little Round Top,” a hill with no defenders and that the Union army’s left side was vulnerable to the Emmitsburg Road. Johnston demonstrated on a map that the Union left side extended from Cemetery Hill, followed the southwest direction of the Emmitsburg Road, and ended at Codori farm. However, in truth, Johnston was mistaken about the location of the Union lines. The actual flank was secured at Cemetery Hill and proceeded south towards the two Round Top Hills. Unfortunately for the South, Johnston’s report was inaccurate.

Using Johnston’s information, Lee decided to attack both sides of the Union Army simultaneously in a coordinated attack that would happen that afternoon. Soldiers under General Richard Ewell will show themselves near the Union at Culp’s and Cemetery hills. Longstreet’s Corps will move south, make the main attack on the Union left, and take control of Little Round Top and Big Round Top, which are at the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. Johnston said that these two hills were not defended. Johnston was responsible for leading Longstreet’s Corps to the starting point.

After several delays, including returning on its path to avoid being seen by Federal signal men on Little Roundtop, Brigadier General Gouverneur Warren noticed Confederate regiments moving away from III Corps’ left and heading straight toward his location. He realized these regiments could easily reach Little Round Top and turn the Union left flank. Warren quickly started looking for any nearby unit to stop the approaching enemy. One of his couriers eventually found Colonel Strong Vincent, who commanded the 3rd Brigade of the First Division, which belonged to V Corps. Vincent understood the importance of the hill and immediately took action, leading his brigade toward the critical position. Meanwhile, Longstreet Corps finally arrived at its launching point, only to discover the Union III Corps, with more than 10,000 men, directly in front of them on Emmitsburg Road. However, this was surprising because Johnston had informed Lee that there were no Union soldiers next to Emmitsburg Road.

Longstreet, who disagreed with Lee on the attack plan, still followed his orders. So, he sends his men forward at around 4:00 p.m. The fighting throughout the afternoon and into the evening is intense at Devil’s Den and Little Round Top – where one of the most significant events of the Civil War happens – the famous charge of the 20th Maine, the regiment on the left of the Union line, occurs. Running out of ammunition and with no other choice, Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, the commander of the 20th, unexpectedly orders a bayonet charge against the attacking 15th and 47th Alabama. This sudden charge saves the Union army from defeat at Gettysburg and sweeps the Alabamians from Little Round Top. The fighting also occurs at the Wheat Field, the Peach Orchard, and Cemetery Ridge.

The fighting stopped late in the evening, around 10:30, but many were hurt or killed. Approximately 20,000 soldiers were either captured, wounded, missing, or dead. If we count it as a separate battle, the second day of Gettysburg would be listed as the tenth deadliest battle of the whole war.

Pickett’s Charge

The next day, on July 3, 1863, General Lee thinks that the enemy is weaker and decides to attack in the middle to take advantage of the progress made on the previous day. At 2:00 p.m., after the most extensive artillery bombardment of the war – some say it could be heard up to 150 miles away – General Lee sends 12,500 soldiers from three Confederate divisions led by Major General George Pickett, Brigadier General J. Johnson Pettigrew, and Major General Isaac Trimble towards the center of the Union line. An hour later, after losing 60% of their soldiers, with at least 1,100 killed instantly and another 4,000 wounded, many of whom would soon die, the attack was pushed back. As the few surviving soldiers return to the Confederate line, General Lee reportedly says, “It’s all my fault.” The next day, the Army of Northern Virginia retreated from Gettysburg and returned to Virginia. The Battle of Gettysburg is now finished.

After Gettysburg

Johnston stayed with the army and later became a Lieutenant Colonel. He gave up at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, together with the Army of Northern Virginia.

On January 27, 1865, Johnston became a father to a son named Robert Edward Lee Johnston (January 27, 1865 – September 13, 1909). He called his son after his commanding general as a tribute. Johnston informs Lee about the decision, and Lee responds by saying, “I am grateful for the great honor you give me by naming your son after me.” The child grows up, becomes a successful doctor, and lives for ten years longer than his father, passing away in 1909. Dr. Johnston is laid to rest in the Presbyterian Cemetery.

Two Wives

He married Mary G. Ege (February 4, 1832 – January 28, 1879) on June 21, 1859. Their marriage ends in divorce. After the war, Johnston married Sara Campbell Watts (May 24, 1854 – March 30, 1893).

Family Plot in the Presbyterian Cemetery

Johnston lived in thirteen states while working as an engineer for different railroads. He passed away on December 24, 1899, at his East Orange, New Jersey residence. He was laid to rest in Section 44, Plot 161, at the Alexandria Presbyterian Cemetery on December 28, 1899. Interestingly, his first and second wives were buried in the same plot.

Lost Cause Ideology

While the concept known as the “Lost Cause Ideology” mainly blames General Longstreet for General Lee’s failure at the Battle of Gettysburg, it also holds Johnston responsible. Did Johnston provide false information to General Lee? Scholars have been debating this question for a long time. Some argue that Johnston had a bad day, while others attribute the failure to the absence of Confederate cavalry, as General J.E.B Stuart was elsewhere. However, it is most likely that Johnston misunderstood his location, thinking he was on Little Round Top when he was on the slopes of Big Round Top.

Consequently, he never saw the Union troops that the Confederates encountered on July 2, 1863, afternoon. The “Lost Cause Ideology,” primarily promoted by former General Jubal Early, asserts that the Confederacy fought a just war and was overwhelmed by the North’s industrial power.

Interestingly, several of General Early’s direct descendants, including his great-niece Dorthy Crowe, are buried in the Alexandria Presbyterian Cemetery. Despite this family connection, Dorthy insisted that most of her relatives were Unionists, unlike her great uncle Jubal, whom she described as an “irascible bastard” during an interview in 2019. After General Early died in 1894, Dorthy’s mother received his ceremonial sword and later passed it down to Dorthy. However, the current whereabouts of the sword are unknown. An energetic and lively person, Dorthy retained her vitality and spunk well into her 90s. Unfortunately, she passed away in 2021 after a brief illness.

Sources of Information

Cooling, III Benjamin Franklin; Owen II, Walton H. Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington. White Mane Publishing Company. Shippensburg, PA. 1988.

Pippenger, Wesley E. Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volume 1, Family Line Publications, Westminster, MD, and Heritage Books, Inc., Bowie, MD. 1992.

Hakenson, Donald C. This Forgotten Land Volume II, Biographical Sketches of Confederate Veterans Buried in Alexandria, Virginia. Donald Hakenson. Alexandria, Virginia. 2011.

Robert, William J. Illustrated by Christine Yongbluth.Lost Alexandria: An Illustrated History of Sixteen Destroyed Historic Homes in and Around Alexandria, Virginia. Voyage Printing. Alexandria, Virginia. 2017.

See the official website of Military Images Digital for an excellent article on Samuel Johnston. Accessed October 2022.

See the official Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park for an excellent blog on Capt. Samuel R. Johnston. Accessed May 2022.

See the official website of Rebellion Research and an article on the Battle of Gettysburg – Day 2. Accessed October 2022.

See the essay “To Consider Every Contingency” by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Capt. Samuel R. Johnston, and the factors

that affected the reconnaissance and countermarch, July 2, 1863. written by Karlton D. Smith. Accessed October 2022.