In the tumultuous days following President Lincoln’s assassination, a lesser-known tragedy unfolded on the Potomac River. As the nation grappled with the loss of its leader and the hunt for his killer intensified, a collision between two vessels resulted in the deaths of 87 people, including recently freed Union soldiers and civilian volunteers. This is the story of the Black Diamond disaster – a tale of sacrifice, duty, and unforeseen consequences in the pursuit of justice.

This tragedy unfolded on April 24, 1865, when a large sidewheel steamer, known as the “Massachusetts,” collided with the coal barge “Black Diamond” on the Potomac River. The disaster occurred at approximately 1:00 a.m. as the steamer navigated from Alexandria to City Point, Virginia. In total, 87 lives were lost, including four United States Quartermaster Department employees who were later laid to rest in the Alexandria National Cemetery.

Prelude to Tragedy: From Camp Parole to the Black Diamond

The steamboat was carrying about 300 passengers, many of whom were Union soldiers recently released from prisoner-of-war camps in the Southern states. A significant number of these soldiers were from the 16th Connecticut regiment, which had been captured when the Confederates seized the Union Garrison in Plymouth, North Carolina, on April 20, 1864. The 16th Connecticut was a regiment that had faced numerous challenges and tragedies throughout the war.

The regiment suffered horrific casualties at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, just weeks after being formed. Late in the afternoon of that fateful day, the newly minted regiment was attacked by A.P. Hill’s Light Brigade, resulting in devastating losses. The regiment’s capture at Plymouth and subsequent imprisonment further added to their hardships.

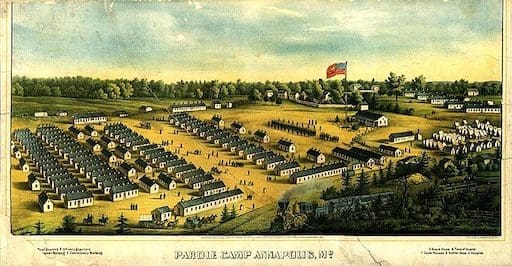

After their liberation from Andersonville, where they suffered from severe malnutrition and illness, these soldiers spent time recuperating in hospitals or at Camp Parole in Annapolis, Maryland, as they worked to regain their health and strength.

Camp Parole was one of three Union facilities established during the American Civil War to process and house released Union prisoners of war. Located just outside Annapolis, it served as temporary accommodation for freed Union soldiers awaiting formal exchange for Confederate prisoners held in the South. It also served as the headquarters for Clara Barton, the Civil War nurse who later founded the American Red Cross.

As these soldiers embarked on their journey to rejoin their regiments in Raleigh, North Carolina, aboard the “Massachusetts,” they unwittingly sailed into the path of another vessel with a very different mission – one that would tragically alter the course of their lives.

A Mission to Capture Lincoln’s Assassin

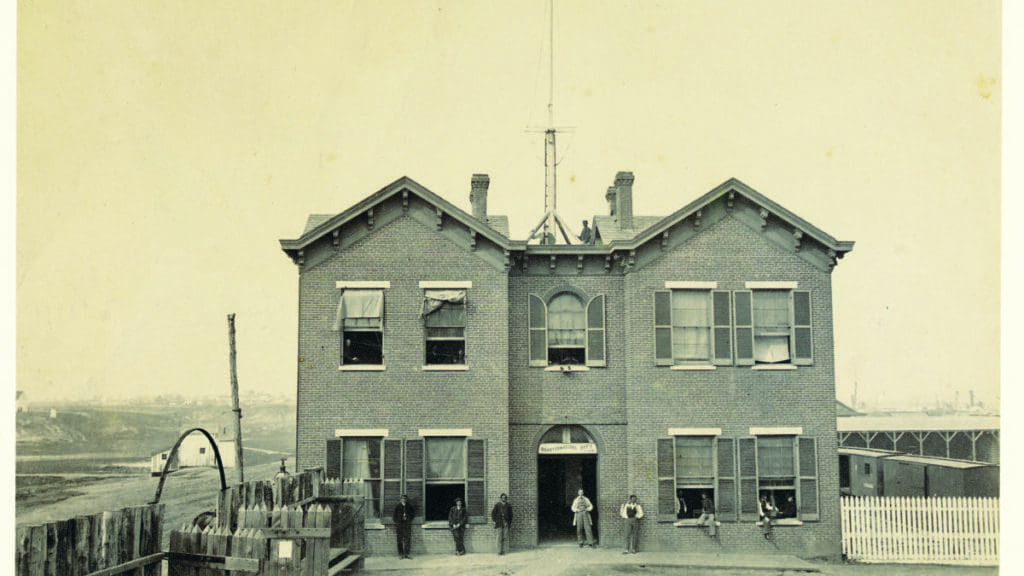

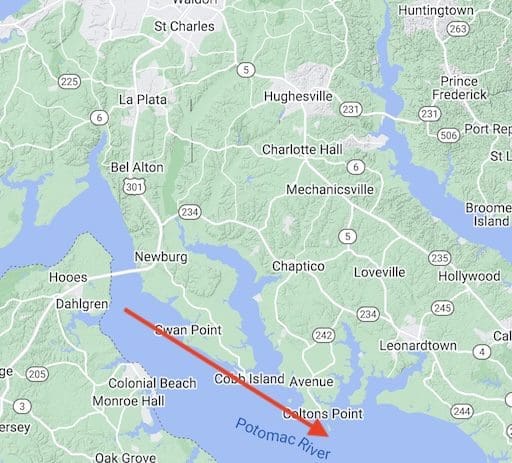

The “Black Diamond,” a 120-foot long, iron-hulled, shallow-draft boat perfectly suited for navigating the shallow waters of the Potomac River, was stationed as a sentry ship near St. Clements Island, tasked with preventing J. Wilkes Booth and his accomplice, Davey Herold, from crossing the river from Maryland to Virginia following the assassination of President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC. Manned by a crew of 11 ardent volunteers, the barge headed from Alexandria, Va., to Piney Point, Md., early that day before steaming back up the Potomac and anchoring near the Blackistone Island 1 Lighthouse at approximately 12:35 a.m. on April 24. The “Black Diamond” was one of many ships in the Quartermaster Division’s flotilla positioned along the Potomac.2

St. Clement’s Island holds historical significance as the site where English settlers first landed on Maryland’s shore in 1634, marking the beginning of the colony’s establishment. The photograph of the island was taken during a private tour led by Karen Stone, a historian with extensive knowledge of the Black Diamond tragedy and the island’s rich history.

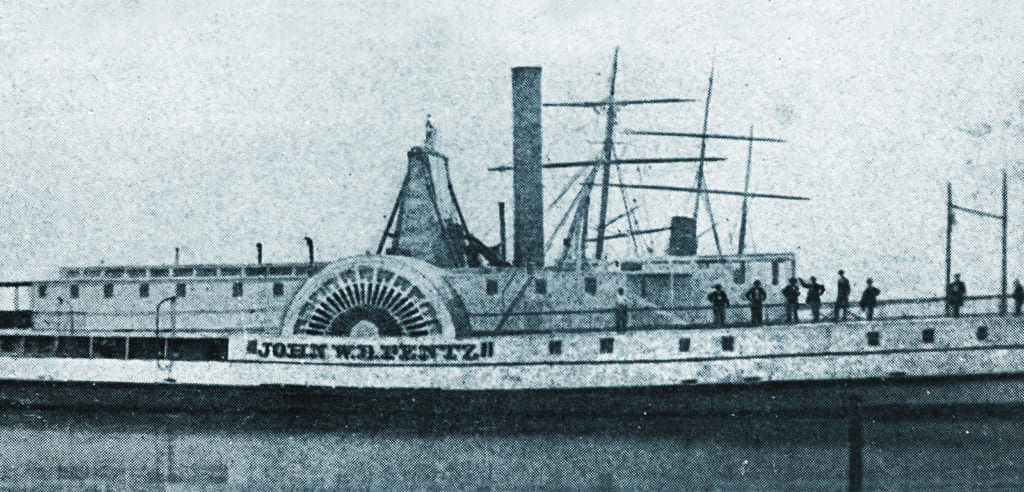

Tragedy struck when the privately owned steamer “Massachusetts,” also known as the “JWD Pentz,” collided with the “Black Diamond” on its port side just before 1:00 a.m. on April 24, 1865. The “Massachusetts,” under contract with the U.S. government to make regular runs between Washington and City Point/Fort Monroe, was transporting a regiment of Union soldiers to City Point, Virginia. Despite being a civilian vessel, the “Massachusetts” was crucial in transporting troops and supplies during the war. (It is important to note that this steamer was not the “USS Massachusetts” (1860), a Union Navy steamer active during the Civil War.)

Believing the “Black Diamond” to be a rescue ship, the “Massachusetts” Captain instructed the soldiers to jump onto the smaller vessel. About 150 men reportedly jumped, with approximately half drowning.

Those who jumped added to the speed at which “Black Diamond” sank in 3½ fathoms of water: less than three minutes. Many others leaped into the Potomac in an attempt to save themselves.

The Black Diamond Disaster: Lives Lost and Recovered.

Among the casualties were 13 men from the 16th Connecticut regiment, adding to the already substantial losses the regiment had suffered throughout the war. The tragedy struck a particularly poignant note for this battle-weary group of soldiers who had endured capture, imprisonment, and the hardships of Andersonville.

Out of the 87 men who perished, only 26 have been identified by name. In all, 37 bodies were recovered, with most taken to Point Lookout before being sent on for burial.

The bodies of the four Quartermaster’s Department individuals were among those recovered. They were sent to Alexandria, where they were laid to rest in the Military Cemetery, now known as the Alexandria National Cemetery.

While some victims’ remains were recovered and sent to their respective homes for burial, many others who lost their lives in the incident were never found. These unfortunate souls are believed to still lie at the bottom of the Potomac River.

The gravity of the disaster is evident in the official report filed by the Quartermaster, Capt. J.G.C. Lee, A.Q.M, In his stark account to his superiors, he wrote:

Depart Quartermaster OfficeNote: This report is presented exactly as it appears in the original document, including any spelling or punctuation irregularities of the time. This firsthand report, preserved in the National Archives and shared by Karen Stone, Museum Division Manager of St. Mary’s County Museum, underscores the tragic scale of the event and provides a vivid, contemporary account of the disaster and its immediate aftermath.

Alexandria, VA Apl 25th 1865

General D. H. Rucker

Chief Qt. Mr.

Washington Depot

I have the honor to report that the Steamer "Black Diamond" sent down the River on Sunday morning on guard duty with ten men, employees of this depart, belonging to the 3rd Regt. G.M. Vols, as a guard, was run into near Blackistone Island by the Steamer "Massachusetts" about one o'clock Monday Morning and was immediately sunk in three and a half fathoms of water.

I regret to add that six of the men composing the guard are reported lost.

The "Massachusetts" was loaded with soldiers of whom about sixty are reported lost.

From what I can learn the cause of the disaster was extreme carlessness of the pilot or master of the "Massachusetts".

Very Respectfully,

Your Obt Servt

J.G.C. Lee

Capt. A.Q.M.

Despite sustaining damage to its bow above the waterline, the “Massachusetts” remained at the scene until 8:30 a.m. before making its way to Point Lookout for repairs. Point Lookout was the site of a military hospital and a prisoner-of-war camp where captured Confederate soldiers were held. The “Black Diamond,” which sank in shallow waters, remained visible for many years, serving as a haunting reminder of the tragic event.

The Pursuit and Death of John Wilkes Booth

On April 26, 1865, members of the 16th New York Cavalry tracked down Booth and Herold to a barn on Richard Garrett’s farm near Port Royal, Virginia. Ironically, Booth and Herold had successfully rowed across the Potomac River to Virginia, landing at the mouth of Gambo Creek on Sunday, April 23, 1865 – the very same day as the Black Diamond tragedy. This successful crossing occurred despite the efforts of vessels like the “Black Diamond” to prevent it.

While Herold surrendered, Booth wanted to fight to the death. In response, the troops set the structure ablaze to force Booth out. The troopers decided to flush Booth out and set fire to the barn by piling dried pine branches against the building.

As the flames engulfed the barn, they illuminated the building enough to show Booth leaning on a crutch with a carbine in one hand and a revolver in the other. As Booth turned towards the barn door, a single shot was heard.

Boston Corbett, declaring, “Providence guided me,” fired upon Booth, striking Booth in the neck and paralyzing him. Unable to move, Booth was pulled from the burning barn by the soldiers and carried to the porch of the Garrett farmhouse, where he succumbed to his injuries at about 7:20 a.m., nearly 12 days and to the moment after President Lincoln had succumbed to his wounds at The Petersen House in Washington, D.C., on April 15, 1865.

A Memorial to the Fallen: Honoring Quartermaster Department Employees

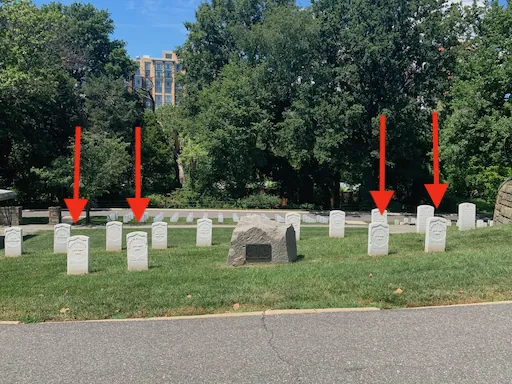

In the Alexandria National Cemetery, a granite memorial stone was placed to honor the four United States Quartermaster Department employees who lost their lives in the tragic collision between the “Black Diamond” and the “Massachusetts.” This granite marker replaced an earlier stone that had initially been placed to mark the graves of these four civilians.

The memorial, situated adjacent to the cemetery’s flagpole, features a plaque that pays tribute to the men who perished that fateful night and now rest within the cemetery grounds.

Historical Connections and Coincidences

Interestingly, the placement of this memorial on July 7, 1922, coincided with the fifty-seventh anniversary of the execution by hanging of four individuals connected to President Lincoln’s assassination. These executions took place at the Washington Arsenal on July 7, 1865. Among those executed was David Herold, the very man whom the crew of the “Black Diamond” had been tasked with apprehending when the tragic collision occurred. The juxtaposition of these two events, separated by fifty-seven years, adds a poignant historical context to the memorial dedicated to the four Quartermaster Department employees.

In a fascinating twist of fate, the Alexandria National Cemetery is located at the end of Wilkes Street, named after John Wilkes, a British Member of Parliament. John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Lincoln, was named after John Wilkes, and the two were distantly related. This curious connection between the street name and the infamous assassin adds an extra layer of historical intrigue to the cemetery and its surroundings. Those interested in learning more about the life and influence of John Wilkes can explore our blog post, “The Ugliest Man in Britain,” [here].

Conclusion

The Black Diamond disaster, though tragic in its own right, was overshadowed by the monumental grief that gripped the nation following President Lincoln’s assassination. The death of the beloved leader who had steered the country through its darkest hours left a void that consumed public attention and mourning. In this atmosphere of national sorrow, the loss of 87 lives on the Potomac River, including recently freed Union soldiers and civilian volunteers, received far less attention than it might have in calmer times.

The pursuit and capture of John Wilkes Booth further diverted attention from the Black Diamond tragedy. The dramatic 12-day manhunt captivated the nation, with daily updates and speculation filling newspapers nationwide. The search culminated in the fiery confrontation at the Garrett farm on April 26, 1865, where Booth was fatally shot. This event, occurring just days after the Black Diamond disaster, dominated headlines and public discourse. The death of Lincoln’s assassin provided a sense of closure for a grieving nation while inadvertently overshadowing other tragedies of the time, including the loss of life on the Potomac.

Adding to this tumultuous period, just days after the Black Diamond disaster, an even greater tragedy unfolded on the Mississippi River. On April 27, 1865, the steamboat “Sultana,” overloaded with Union soldiers returning home from Confederate prison camps, exploded and sank near Memphis, Tennessee. This catastrophe claimed the lives of over 1,800 passengers, many of whom were survivors of the infamous Andersonville and Cahaba prisoner-of-war camps. Poignantly, Andersonville was the very same prison where many of those killed in the Black Diamond incident had been held, creating a tragic link between these two disasters. The “Sultana” disaster remains the greatest maritime disaster in U.S. history, yet it, too, was largely overlooked in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination and the end of the Civil War.

The month of April 1865 stands as one of the most consequential in American history. It began with General Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9th, signaling the effective end of the Civil War. Yet, the hope of peace was quickly shattered by President Lincoln’s assassination on April 14th. In the tumultuous days that followed, as the nation mourned and authorities frantically hunted for John Wilkes Booth, two maritime disasters struck: the Black Diamond incident on April 23rd and the sinking of the Sultana on April 27th. This concentration of momentous events serves as a stark reminder of the complex nature of war’s end, juxtaposing victory with profound loss. Together, these April events underscore the intricate tapestry of triumph and tragedy that marked the conclusion of the Civil War and the beginning of national reconciliation, all compressed into a few short weeks that forever changed the course of American history.

The Black Diamond disaster, though less remembered, stands as a poignant testament to the sacrifices made by ordinary individuals in extraordinary times. It reminds us that behind the grand narratives of history lie countless personal stories of duty, loss, and unsung heroism. As we reflect on these events, we honor not only the famous figures who shaped our nation’s destiny but also the unnamed many whose lives and sacrifices contributed to the fabric of our shared history.

This blog post, originally published on April 23, 2023, has been updated on July 4, 2024, to include additional information and insights related to the Black Diamond tragedy. The revisions were made following a visit with Karen Stone, the St. Mary’s County Museum Division Manager and a historian with extensive knowledge of the Black Diamond incident. We sincerely thank Karen for sharing her expertise, which has greatly contributed to the updated content of this blog post. An excellent source of material on the incident is her article on History.net, which is noted in the Sources of Information below.

Sources of Information

Banks, J. (2013). Connecticut Yankees at Antietam. The History Press.

Cox, M. (2006). [Photograph of the Massachusetts (JWD Pentz)]. HistoryNet. https://www.historynet.com/peril-on-the-potomac-the-sinking-of-black-diamond/

Potter, J. O. (2012). The Sultana tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster. Pelican Publishing Company.

Steers, E., Jr. (1983). The Escape and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. Thomas Publications.

Steers, E., Jr. (2005). Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky.

Stone, K. (2025). Shipwreck on the Potomac: Disaster in the Pursuit of Lincoln’s Killer. The History Press.

Swanson, J. L. (2008). Manhunt: The 12-day hunt for Lincoln’s killer. Mariner Books.

- St. Clement’s Island, originally part of St. Clement’s Manor, was granted to Thomas Gerard by the Second Lord Baltimore in 1639. Gerard became a prominent landholder and political figure in both Maryland and Virginia. The island became known as Blackistone Island after Gerard’s daughter, Elizabeth, married Nehemiah Blackistone. The Blackistone family owned the island for 162 years until the US Navy took control in 1919. In 1962, the island was leased from the Federal government, designated as a state park, and renamed St. Clement’s Island. ↩︎

- Some accounts mistakenly placed this event on the Rappahannock River. ↩︎