The Paulding Family’s Military Roots

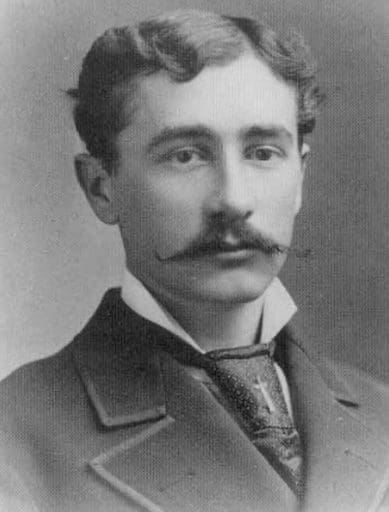

Dr. Holmes Offley Paulding rests in St. Paul’s Cemetery, his gravestone a silent sentinel marking the final chapter of a family inextricably interwoven with pivotal moments in America’s national story. His father, Commander Leonard Paulding of the U.S. Navy, who perished in Panama, and his mother, Helen Jane Offley, are both interred in Arlington, symbolizing their family’s service to the nation.

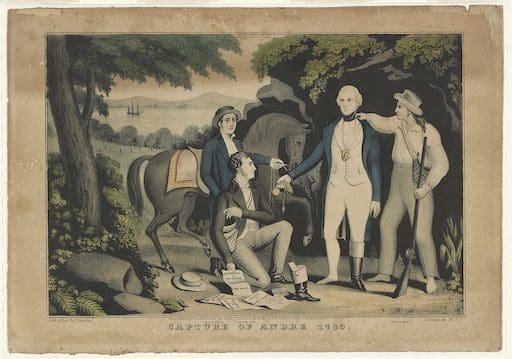

The Paulding family’s military heritage traces back to the Revolutionary War. Holmes Paulding’s great-grandfather, John Paulding, played a crucial role in this era. He was one of the men responsible for the capture of British Major John Andre, who infamously conspired with Benedict Arnold to betray West Point to the British. The capture and subsequent execution of André on October 2, 1780, in Tappan, New York, were partly in response to the British’s execution of Nathan Hale, a revered Patriot. Hale, captured early in his espionage efforts, was executed without a trial, underscoring the harsh realities of war and espionage during the Revolutionary period.

Dr. Holmes Offley Paulding’s grandfather, Hiram Paulding (1797 – 1878), carved out a distinguished career in American naval history. He started as a midshipman in 1811, displaying exceptional bravery and skill during the War of 1812. His leadership commanding the second division at the Battle of Lake Champlain made him a promising young officer.

Post-war, Paulding continued honing his naval expertise on various ships, including the “USS Dolphin” under Lieutenant John “Mad Jack” Percival. He participated in trans-Pacific and Hawaiian expeditions. Steadily rising through the ranks, he commanded the “USS Shark” in 1834 and the “USS Levant” in 1838. By 1841, he was the Executive Officer at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. His promotion to Captain came in 1845.

In 1852, Paulding took command of the Washington Navy Yard. He later commanded the United States Home Squadron. President Abraham Lincoln recognized his strategic insight and appointed him to the Navy Board in 1861. Here, Paulding played a pivotal role in shaping the wartime Navy. He most notably evaluated innovative ironclad warship designs, including John Ericsson’s “USS Monitor.” This revolutionary vessel later made history in its epic duel with the CSS Virginia, signaling a new era in naval warfare.

In a fitting tribute to his distinguished career, the United States Navy honored Rear Admiral Hiram A. Paulding by naming the destroyer ‘USS Paulding’ (DD-22) after him. This recognition not only commemorated his substantial legacy in American naval history but also acknowledged his indirect yet crucial role in one of the most significant naval engagements of the era. The USS Paulding was commissioned and served in 1910 and was active in World War I. Following its naval service, the ship continued its legacy in the United States Coast Guard as the USCGC Paulding (CG-17) from 1924 to 1930, further extending its historical significance.

Fast forward to Paulding’s grandson, Holmes Paulding, who was entwined in another defining moment of American history – the aftermath of the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. This battle was a catastrophic defeat for the U.S. 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Forging His Own Path in Medicine

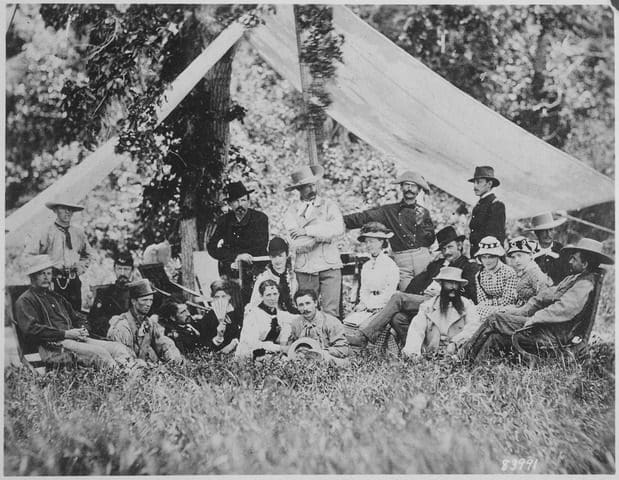

Despite his family’s naval legacy, Dr. Paulding pursued a career in military medicine. After passing his medical board examinations in 1874, he was commissioned as a First Lieutenant and posted to Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory, home to the 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. He developed a close bond with Dr. George Lord, also of the 7th Cavalry. In October 1875, Paulding was assigned as the post-surgeon at Fort Ellis in the Montana Territory under Colonel John Gibbon, a noted Civil War commander.

The Prelude to Little Bighorn: Gold, Conflict, and a Fateful Campaign

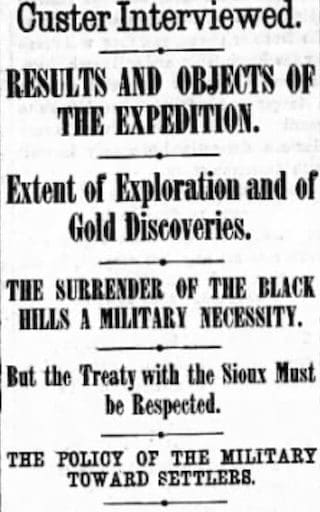

Before delving into Dr. Paulding’s account of the battle’s aftermath, it is essential to understand the events leading up to the Battle of Little Bighorn. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, a region sacred to the Native American tribes, led to an influx of miners and settlers onto these lands. This encroachment sparked significant tensions, as the land was not only sacred but also legally designated to the Native American tribes under the Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Bismarck, North Dakota

Wednesday, September 2, 1874

Page 1

The situation escalated when the U.S. government failed to stop the influx of miners and instead ordered the Native American tribes to return to their reservations by January 31, 1876. The Army, tasked with enforcing the policy, launched a campaign against the Indians, which came to be known as “The Great Sioux War of 1876.”

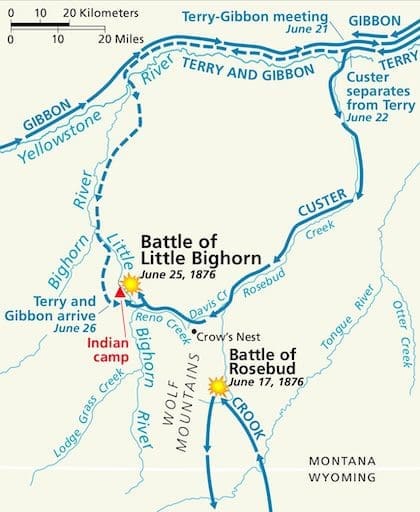

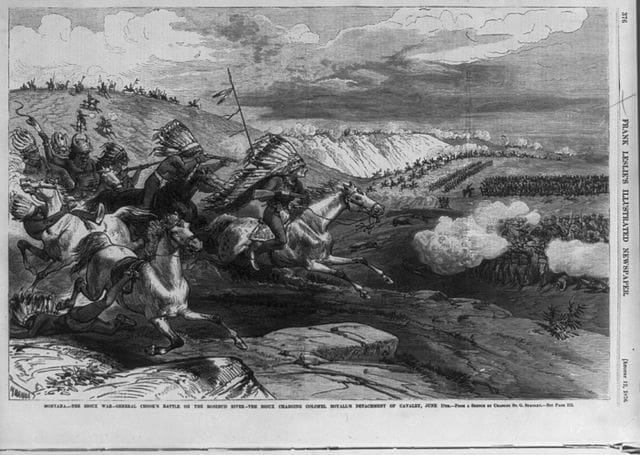

One of the first confrontations occurred at Rosebud Creek on June 17th, where General Crook, a renowned Indian fighter, faced a strong force of Native American warriors. After a fierce battle, Crook was compelled to withdraw to his base near modern-day Sheridan, Wyoming, to regroup and await reinforcements. He would remain there for several weeks and played no part in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which occurred just eight days later.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry marched south up Rosebud Creek towards the Little Bighorn on June 22nd. Dr. Paulding, in his diary, notes a poignant moment before this fateful journey:

“June 19th or 20th – The regiment was reviewed by Generals Terry and Gibbon. I remember Gibbon’s light-hearted words to Custer, jesting him not to be greedy and to save some Indians for the rest of them. It was the last time any of us saw him alive.”

This moment, recalled by Paulding, underscores the gravity of the situation and the fateful nature of the campaign ahead.

Witnessing the Aftermath of Little Bighorn: Through His Diary

Dr. Paulding’s career intersected with a pivotal moment in American history – the aftermath of the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. Assigned to Fort Lincoln, he narrowly escaped the battle’s carnage due to his reassignment to Fort Ellis. However, his medical duties brought him back to document the tragic aftermath. His diary entries from the 27th of June provide a harrowing account:

“June 27th: Our first encounter upon reaching the area was the recently abandoned Indian camp. The once-bustling village, now silent, spread across a valley at least four miles square. The camp was thick with the relics of a sudden departure. Among the debris, we found tin cups, cavalry saddles, and clothing belonging to the 7th Cavalry men. Each abandoned item, each silent echo of life, told a potent story. It was clear from these remnants that Custer and his men had faced not just a defeat but a brutal annihilation. All told the tale – Custer had been literally cut to pieces.“

Dr. Paulding arrived at a scene of devastating casualties – Custer’s battalion had suffered approximately 210 soldiers and 14 officers killed. This aligned with Chief Red Fox’s account of how “the Indians made a curcle around him then rode their horses accross the circle kicking up durt [to] stampead his horses. Then the Indians made their attact” (as cited in “Battle of Little Big Horn,” 2022). [All quotes from Chief Red Fox’s account are presented verbatim, preserving the original spelling and grammar.]

The state of General Custer’s remains stood out distinctly among the casualties. Unlike many others at the site, Custer’s body was found stripped of clothing but not scalped or mutilated. He had two fatal bullet wounds – one in the left breast and another in the left temple. This starkly contrasted with the fate of others, notably including his brother, Tom Custer, a celebrated Civil War hero. The Native Americans stripped the bodies and scalped them. The women, boys, and old men help kill the wounded and begin the task of mutilation. They crushed skulls, tore out eyes, severed muscles and tendons, hacked off limbs, and separated heads from bodies. According to Indian beliefs, these mutilated soldiers would not move through the next world in comfort. The fact that Custer’s body was left relatively untouched amidst this scene of brutality made his remains stand out even more distinctly.

Tom Custer’s body was gruesomely mutilated to the extent that he was only identifiable by a known tattoo. This grim list of the fallen included their nephew, Autie Reed; Lt. James Calhoun, Custer’s brother-in-law; and Capt. Myles Keogh, famed for his heroism at Gettysburg. Amidst the wreckage and sorrow, a poignant note emerged: the lone survivor from Custer’s immediate command was discovered. As Chief Red Fox recalled, “Captain Kegho was the last man to be killed and his horse Comanche was the only horse alive” (as cited in “Battle of Little Big Horn,” 2022).

During this sad task, Dr. Paulding also encountered the bodies of many friends he lost in the battle, including Second Lieutenant Jack Sturgis, 1LT James Ezekiel “Jimmy” Porter, Captain George Yates, and his dear friend, First Lieutenant Dr. George Lord. The mutilation of the bodies by the Native Americans left many almost unrecognizable, adding a layer of personal tragedy to his duty.

As Dr. Paulding identified the bodies, he chronicled the last stand, signifying the boiling point of the Plains wars. This military defeat had profound cultural and political consequences, epitomizing the high cost of American expansionism colliding catastrophically with Native American struggles to maintain their ways of life and sovereignty. As Chief Red Fox noted, “the Indians had better guns than the soldiers good horsemen and knew the country and planed how to fight the battle…” (as cited in “Battle of Little Big Horn,” 2022).

Most of the bodies from the battle, including that of George Armstrong Custer, were initially buried where they fell. A year later, on October 10, 1877, Custer was reinterred with full military honors at West Point Cemetery. In 1881, most of the known battlefield burials were moved to a mass grave on top of Last Stand Hill, marking a solemn consolidation of this tragic chapter in American history.

A Final Stand and Surrender: The Tragic End of Crazy Horse’s Resistance

In the winter of 1876-77, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, still buoyed by their success at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, faced a formidable challenge. The U.S. Army, under the command of General Nelson Miles, launched a robust counteroffensive. This clash of forces culminated on January 8, 1877, marking a pivotal moment in the conflict. Crazy Horse and his outnumbered troops found themselves in a dire situation. They were cornered in their camp along the Tongue River in Montana, equipped with scarce ammunition and obsolete weaponry while facing the overwhelming firepower of the U.S. Cavalry.

The situation for Crazy Horse and his warriors grew increasingly desperate as they mounted a valiant defense. Their resources diminished to the point where they resorted to traditional bows and arrows, primarily to delay the enemy and ensure the escape of their women and children amid a harsh blizzard. However, the inevitability of defeat loomed large. On May 6, 1877, recognizing the futility of further resistance against the well-armed U.S. forces, Crazy Horse surrendered with approximately 1,100 followers at the Red Cloud reservation near Fort Robinson in Nebraska. This surrender marked the end of a significant chapter in Native American resistance. Tragically, Crazy Horse’s life came to a sudden and violent end five months later. He was fatally stabbed under contentious circumstances, reportedly while resisting confinement.

Career Cut Short by Tragedy

In the years after Little Bighorn, Dr. Paulding continued his medical work at Baltimore and the Dakota Territory posts. On January 13, 1880, he married Mary E. French, with whom he had two daughters – Katherine Whitehorne and Holmes Paulding Allen. Neither daughter had children, marking an end to this branch of the Paulding. Sadly, his promising career and life were cut short at just 30 years old due to a sudden rheumatism attack while on duty. His premature death represented an immense loss of his talents to military medicine and his local community. It also marked a final abrupt end to this branch of the Paulding’s centuries-spanning family tree – though the more prominent clan’s enduring legacy survives through naval history.

Conclusion

In just three short decades, Dr. Holmes Offley Paulding led a life exemplifying selfless service to corps and country – a defining hallmark of the Pauldings before him. Though his light dimmed too quickly, his dedication as a military physician and connections to a pivotal event at Little Bighorn preserved his family’s legacy at an essential crossroads in America’s national story – destined to persist through the annals of history.

Dr. Paulding’s detailed accounts from the aftermath of the Battle of Little Bighorn offer us invaluable insights into this tumultuous period. His observations provide a unique human perspective on the events, adding depth to our understanding of the battle’s impact on the participants and the course of American history. Through his eyes, we see the immediate consequences of the conflict and the human cost of a pivotal moment that epitomized the clash between American expansionism and Native American resistance. His accounts help bridge the gap between historical narratives and personal experiences, offering a more nuanced understanding of this critical event in the American West.

Dr. Paulding was laid to rest in St. Paul’s Cemetery, marking the end of a life dedicated to service and leaving a legacy of courage and commitment. His wife, Mary French Paulding, outlived him by many years, remarrying prominent Washington lawyer Joseph A. Rice, who passed away in 1901.

When Mary French died in 1934, she was laid to rest in the same cemetery lot as her first husband, uniting them once more. Though Dr. Paulding’s promising career and life met a premature end, his courageous account from the aftermath of Little Bighorn remains immortalized. While his branch of the family tree may have abruptly ended, the Paulding legacy persists as an indelible thread through the enduring tapestry of American history.

| HOLMES OFFLEY PAULDING Captain and Assistant Surgeon U. S. Army died May 1, 1883 aged 30 years |

Sources of Information

Morgan, T. (1995). A Shovel of Stars: The making of the American West 1800 to the present. Simon & Schuster.

Pippenger, W. E. (2014). Tombstone inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia (Vol. 5). Heritage Books.

Hurst, B. V. (Ed.). (2021). An Infernal Failure: Little Bighorn Diary 1876 by Dr. Holmes Offley Paudling. Big Byte Books.

Battle of Little Big Horn, Memoirs of Chief Red Fox (1870-1976). (2022, September 10). Ya-Native. https://www.ya-native.com/blog/𝐁𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞-𝐨𝐟-𝐋𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞-𝐁𝐢/

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. (2022). St. Paul’s Episcopal Cemetery, 2022 NRHP Draft Final. Retrieved from https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/100-0143_St_Pauls_Episcopal_Cemetery_2022_NRHP_DraftFinal.pdf

Utley, R. M. (1969). Custer Battlefield National Monument, Montana (now Little Bighorn Battlefield). National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 1. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://archives.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/2450/665/CUSTER?sequence=1