Early Life and Military Career

Lewis Nicola was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1717 into a Huguenot family with a strong military tradition; both his father and grandfather served as officers in the British army. Following in their footsteps, Nicola began his military career as an ensign in 1740. He rose through the ranks to become a major, and in 1766, he was appointed commander of Fort Charles near Kinsale, Ireland.

Emigration to America and Civil Career

In 1766, Nicola resigned his commission and emigrated to the United States, settling in Philadelphia. There, he pivoted his career towards civil engineering. In 1769, Nicola founded and edited the “American Magazine,” which included transactions of the American Philosophical Society, of which he was a member.

Role in the American Revolution

With the onset of the American Revolution, Nicola’s military expertise came to the forefront. He was appointed barracks-master-general of Philadelphia in early 1776 and later commanded the city guard. In December 1776, he received the commission of town major in the state service, a position he held until 1882. Nicola was instrumental in the war effort, publishing a military treatise in 1776, planning river defense boats, devising magazine plans, and creating maps of British damage in Philadelphia. His proposal for a regiment of invalids, meant to serve both as a veterans’ refuge and a training corps, led to his commission as its colonel in 1777.

The Newburgh Letter: Nicola’s Controversial Proposal to Washington

On May 22, 1782, Colonel Lewis Nicola, stationed at his army quarters in Newburgh, New York, penned a significant letter to George Washington, known as the Newburgh letter. In this letter, Nicola initially highlighted the financial struggles facing him and his men, emphasizing the issue of unpaid salaries. This problem stemmed from the Articles of Confederation, which granted Congress the power to establish an army during wartime but did not oblige it to levy taxes for its maintenance. Consequently, most of the Army had been awaiting payment for months, if not years. Nicola argued that this predicament underscored the inherent weaknesses of a republican government.

Delving deeper into his critique, Nicola alluded to Washington’s esteemed capabilities, suggesting that the qualities which led to victory in war could also guide the nation in peacetime. He then controversially proposed a shift in governance, advocating for a mixed government headed by a monarch. Aware of the negative perceptions associated with terms like “tyranny” and “monarchy,” Nicola cautiously recommended the eventual adoption of an alternative title, possibly “king,” believing it would bring substantial benefits.

This correspondence is especially remembered for Nicola’s bold suggestion that Washington himself assume the role of a monarchial head. Nicola’s proposal, aimed at addressing the nation’s challenges, was met with a severe reprimand from Washington, who was deeply distressed by the notion of monarchy in the newly independent nation.

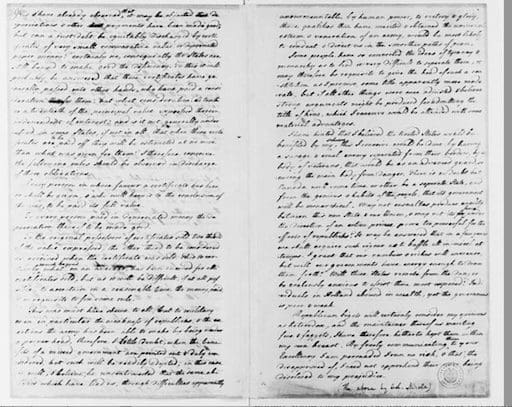

Newburgh May 22d 82

Sir,

With a mixture of great surprise & astonishment I have read with attention the Sentiments you have submitted to my perusal. Be assured, Sir, no occurrence in the course of the War, has given me more painful sensations than your information of there being such ideas existing in the Army as you have expressed, & I must view with abhorrence, and reprehend with severity—For the present, the communicatn of them will rest in my own bosom, unless some further agitation of the matter, shall make a disclosure necessary.

I am much at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my Country. If I am not deceived in the knowledge of myself, you could not have found a person to whom your schemes are more disagreeable—at the same time in justice to my own feeling I must add, that no man possesses a more sincere wish to see ample Justice done to the Army than I do, and as far as my powers & influence, in a constitution[al] way extend, they shall be employed to the utmost of my abilities to effect it, should there be any occasion—Let me [conj]ure you then, if you have any regard for your Country, concern for your self or posterity—or respect for me, to banish these thoughts from your Mind, & never communicate, as from yourself, or any one else, a sentiment of the like nature. With esteem I am Sir Yr Most Obedt Servt

Go: Washington

The foregoing is an exact copy of a Letter which we sealed & sent off to Colonel Nichola at the request of the writer of it.

D. Humphrys Aid de Camp

Jona. Trumbull Jun. Secty

National Archives. (n.d.). To George Washington from Lewis Nicola, 22 May 1782. Founders Online, National Archives. Retrieved December 12, 2023, from https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-08501

Nicola expressed deep regret in his response to Washington on May 23, profoundly affected by Washington’s stern rebuke, and requested an evaluation of his mistakes. Despite the lack of recorded replies to Nicola’s subsequent apologies, their relationship eventually returned to its usual state.

Final Years and Death

In November 1783, Nicola was honored with a brevet brigadier-general rank in the United States Army. His contributions were not only military; he was deeply involved in the planning and suggestions for public service, as evidenced by the Pennsylvania archives. He was also an original member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati.

Post-War Service and Legacy

Nicola spent his final years in Alexandria, Virginia, from 1798 until his death in 1807. Recognized as a Revolutionary War Patriot, he was interred in the Old Presbyterian Meeting House 18th Century Burial Ground in Alexandria. His burial, officiated by Reverend Muir on August 10, 1807, marked the end of a life lived to the age of 90, with his passing attributed to old age. Sadly, the exact location of Nicola’s grave has been lost over time, leaving a gap in the tangible history of this notable figure.

Sources of Information

Pippenger, W. E. (1992). Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volume 1. Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications.

Miller, T. M. (1992). Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, Virginia 1780 – 1820 Volume 2. Heritage Books, Inc.

Wright, F. E., & Pippenger, W. E. (2012). Early Church Records of Alexandria City and Fairfax County, Virginia. Heritage Books, Inc.

Dahmann, D. C. (2022). The Roster of Historic Congregational Members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. Unpublished manuscript.