Former First Lieutenant William Wolf Weisband (August 28, 1908 – May 14, 1967), a member of the U.S. Signal Corps, rests in Alexandria, Virginia’s Presbyterian Cemetery. During the Cold War, he assumed a civilian role within the Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA). He discovered that American cryptanalysts had deciphered the encrypted communications of the Soviet Union’s diplomatic and intelligence channels. Concealed under the alias “Zhora,” William Weisband was a double agent, serving the Soviet Union since 1934. His revelation prompted the Soviets to change their encryption methods, which had serious consequences for American intelligence and left the United States unprepared for North Korea’s invasion of South Korea in June 1950.

Born in Odesa, a city that once belonged to Russia but now resides within Ukraine, Weisband immigrated to the United States during the 1920s and became an American citizen in 1938. He served in the US Army during World War II in North Africa and Italy.

After the war, he worked at Arlington Hall as a language expert, collaborating with the team to decipher codes within the Russian Section. Arlington Hall, located on Arlington Boulevard (U.S. Route 50) between S. Glebe Road (State Route 120) and S. George Mason Drive, currently houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center and the Army National Guard’s Herbert R. Temple Jr. Readiness Center. During Weisband’s time there, he held valuable information about the Soviet Union, which he shared with his KGB handlers. He used ingenious methods for espionage, such as selling jewelry to women at Arlington Hall to gain access to restricted areas. Through this, he discovered the Venona project, which decrypted Soviet messages.

The Venona Project

The Venona Project, based at Arlington Hall, focused on deciphering Soviet communications. The messages revealed a network of hidden agents in the U.S., including Harry Gold, whose capture led to the exposure of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed in 1953 for espionage.

Beyond the Rosenberg affair, Venona’s revelations extended to other covert operatives. Alger Hiss, a prominent government official, was among those implicated. Known by the codename “Ales,” Hiss faced accusations of being a Soviet spy. Despite Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s staunch defense of Hiss’s innocence, Venona’s evidence painted a contrasting narrative. The decrypted messages suggested that Hiss had been a valuable asset to the Soviets, providing them with classified information. The extent of Hiss’s alleged contributions to the Soviet cause was further emphasized by reports that the USSR had awarded him a medal in recognition of his covert activities.

The Hiss case became a contentious issue, with some believing in his innocence while others viewed the Venona evidence as proof of his guilt. The controversy surrounding Alger Hiss and the Venona Project highlighted the complex nature of Cold War espionage and the challenges faced by American intelligence in uncovering and prosecuting suspected Soviet agents.

The Invasion of South Korean

In 1948, the United States successfully deciphered Soviet codes, gaining insights into their global intentions. Weisband, acting as a double agent, informed the Soviet Union about the code breach. The Soviets quickly strengthened their encryption, causing a setback for American code-breaking efforts. This created a blind spot, and the U.S. failed to detect the growing Soviet military presence in North Korea.

On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched a surprise invasion of South Korea, a major U.S. intelligence failure that had lasting consequences for the region. The resulting war caused over 3 million casualties, mostly civilians, and claimed the lives of 33,000 American soldiers, with another 103,000 wounded. William Weisband’s actions have been blamed for the damage to the U.S. SIGINT program against the Soviet Union and the subsequent intelligence failure.

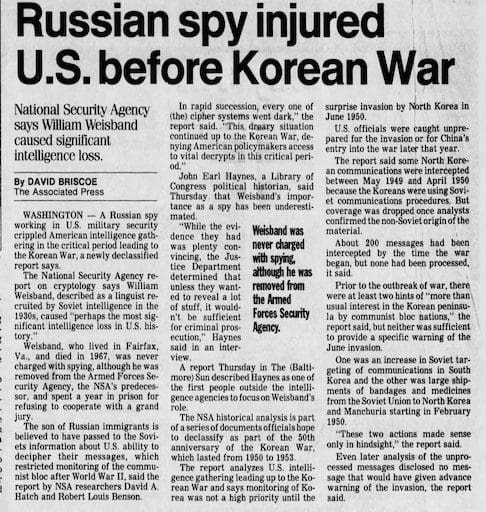

30 Jun 2000, Fri · Page 74.

Arrest and Sentence

In 1950, Weisband faced suspicion and was suspended from work. He was summoned before a federal grand jury in Los Angeles to investigate Communist Party and Soviet espionage activities on the West Coast. When he failed to appear a second time, he was arrested and found in contempt, receiving a one-year sentence at the Federal Labor Camp on McNeil Island, Washington. While not explicitly charged with espionage, his actions centered on contempt of court.

22 Aug 1950, Tue · Page 22

Life in Alexandria, VA

After his release, Weisband became an insurance agent in Alexandria. According to his son, his father had the most extensive ledger of outstanding dues in the state, regularly visiting residences to collect payments.

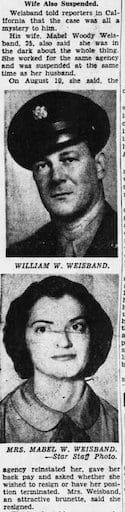

Marriage

On January 15, 1949, Weisband married Mabel Elizabeth Woody Ricker (June 8, 1925 – August 27, 2015), a government analyst who briefly worked at Arlington Hall. She was inadvertently involved in the suspicion surrounding Weisband during his espionage investigation. The couple had four children. After Weisband’s death, Mabel remarried and was laid to rest at the National Memorial Park in Falls Church, Virginia.

22 Aug 1950, Tue · Page 22

Death and Burial

Weisband passed away on May 14, 1967, from a heart attack while driving his family to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. His funeral was attended by many African American clients who gathered on the lawn to pay their respects. He was buried in Section 1, Plot 1 of the Presbyterian Cemetery, adjacent to the Alexandria National Cemetery, where veterans of the Korean War—an event some associate with his actions—are laid to rest. Ironically, his gravestone was provided by the government he had betrayed.

| WILLIAM W WEISBAND VIRGINIA 1st LT SIGNAL CORPS WORLD WAR II AUG 28 1908 May 14 1976 |

Sources of Information

Benson, R. L. (n.d.). The Venona Story. Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.nsa.gov/portals/75/documents/about/cryptologic-heritage/historical-figures-publications/publications/coldwar/venona_story.pdf

Hatch, D. A., & Benson, R. L. (2000). The Korean War: The SIGINT background. Center for Cryptological History, National Security Agency. Retrieved 2023, from https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/13/2002761763/-1/-1/0/KOREAN-WAR-SIGINT-BACKGROUND.PDF

Conservapedia. (n.d.). Bill Weisband. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.conservapedia.com/Bill_Weisband

Schindler, J. (2021, February 21). The greatest intelligence disaster in U.S. history. Retrieved 2023, from https://topsecretumbra.substack.com/p/link-the-greatest-intelligence-disaster

NOVA. (2022, January). Family of spies [Interview with William Weisband Jr.]. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/family-of-spies/

Obits.al.com. (n.d.). Mable Flanagan. Retrieved 2023, from https://obits.al.com/us/obituaries/birmingham/name/mabel-flanagan-obituary?id=10665145

The Presbyterian Cemetery and Columbarium. (n.d.). Archives.