Often mocked for his unusual looks, John Wilkes was much more than his reputation as the Ugliest Man in Britain. Despite his misaligned eyes and striking features, he was a brilliant political thinker, a fierce advocate for free speech, and a man whose charm won over even his harshest critics. But how did a man once called “too ugly to look at” become one of Britain’s most influential figures?

Who Was the Ugliest Man in Britain?

The ugliest man in Britain. He had a very unpleasant appearance, with his eyes not appropriately aligned and a jaw that stuck out. Still, he also had fantastic charisma and was famous for his cleverness, which people claimed could quickly make you overlook his unattractiveness.

He proudly claimed it only took him half an hour to talk so much that his face disappeared. He also stated that having a one-month advantage over his rival regarding looks would guarantee him victory in any romantic relationship. His intelligence was just as swift as his actions when Lord Sandwich remarked, “Wilkes, you will meet your demise either on the gallows or from the pox.” In response, Wilkes cleverly replied, “That depends on whether I adopt your lordship’s principles or pursue your mistress.” When one of his colleagues became angry and declared, “I will no longer be your butt for jokes,” Wilkes cheerfully replied, “That’s perfectly fine; I never liked empty butts anyway.”

The Early Life of the Ugliest Man in Britain

Born on October 17, 1725, and educated in the Dutch Republic, he married Mary Meade in 1747 because she had a property in Buckinghamshire that provided her with money. They had a daughter named Mary, but she was often called Polly. However, their marriage didn’t work out, and John and Mary separated in 1761.

After that, he gained a reputation as a ‘rake’ (a term for a reckless and womanizing man), and while he had other relationships, his devotion to Polly never faded. But it wasn’t just his personal life that made headlines—Wilkes was about to shake up British politics in a way no one expected.

How the Ugliest Man in Britain Became a Political Icon

In 1757, Wilkes won a seat in Parliament representing Aylesbury. Once in power, he became one of Britain’s loudest voices for free speech, refusing to let the government silence dissent.

Among his friends and other people he knew in London was Arthur Lee, Richard Henry Lee’s brother from Virginia. In 1776, Richard Henry Lee was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress and proposed the idea of the United States being independent of Great Britain. He said, “The thirteen colonies should be free and independent states. They should no longer have any loyalty to the British king, and their political connection with Great Britain should be completely severed.“

How the Ugliest Man in Britain Lived During George III’s Reign

In 1751, Frederick, the Prince of Wales and the next in line for the English throne died suddenly from a lung injury. Frederick’s oldest son, Prince George, is chosen to be the next Prince of Wales. His grandfather, George II, selects John Stuart, the 3rd Earl of Bute, a Scottish man, as his tutor. Bute also becomes close to Frederick’s widow, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, and there are rumors that they are having a romantic relationship.

After King George II died in 1760, his grandson, the Prince of Wales, became the new king and was named George III. At 22, he is the first British-born ruler from the House of Hanover and is well-liked. Thanks to Bute’s guidance, the new king received a high-quality education and could read and write in English and German.

The Jacobites Rebellion

In 1745, “Bonnie Prince Charles,” who wanted to be the king, returned to Scotland. His father was James Francis Edward Stuart. James was also called the Old Pretender and was James II’s son. James II was the last Catholic King of England. He lost his crown during the Glorious Revolution in 1688.

Known as Jacobites, Bonnie Prince Charles and his army caused a lot of trouble in Scotland and northern England for eight months before Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the third son of George II, led an army that defeated the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden on April 16, 1746. After that, anyone connected to Scotland was suspected of supporting the Jacobites.

Whigs and Tories

As a Scott, Bute was viewed with suspicion by many as a Jacobite, especially by the Whigs, who were one of two political parties in Great Britain during the 18th century.

Initially, the word “Whig” referred to horse thieves and Presbyterians. It conveyed the idea of not conforming to norms and rebelling against authority. Over time, it started to describe people who wanted to prevent the hereditary heir from ascending to the British throne.

The opposition was the Tories, who were outlaws that followed the Catholic faith and supported the right of James II to be king, even though he was Catholic.

The Whigs were the most powerful political party in the government of George III.

Bute was elevated to First Minister.

In 1762, Bute became the leader of the government as George’s First Minister (also known as the Prime Minister nowadays). During that time, Bute also began publishing a weekly newspaper called “Briton,” which supported the government and was funded by the treasury. The newspaper had around 250 copies per edition, the typical periodical number.

Wilkes, in reaction, creates a magazine titled “The North Briton” to criticize Brute. He claims that Scotland has too much influence on England’s government and accuses a Stuart of having an inappropriate relationship with the King’s mother. This publication becomes very popular, selling thousands of copies with each new issue.

The first magazine, The North Briton No. 1, declared that ‘the freedom of the press is a fundamental right for every British citizen … under a Stuart ruler, the government has blatantly disregarded this freedom’. In each subsequent edition, Wilkes continued to criticize Bute, much to the pleasure of his readers.”

On February 19, 1763, in The North Briton No. 38, the Pretender published a letter to his “relative” Bute: “Thanks to your kind influence, everything now looks very promising. Wherever you go, the national symbol of Scotland, the Thistle, flourishes under your steps. Supporters of the Stuart dynasty are no longer sad…

In his book from 1962 called “Portrait of a Patriot, a Biography of John Wilkes”, Charles Trench mentions that Bute, because of “The North Briton”, becomes the most despised minister in England.

On April 8, 1763, Bute stepped down from his position and was replaced by George Grenville, a politician from the Whig party.

After accomplishing his objective of defeating Bute, Wilkes decides to take a vacation in Paris. At the same time, it appears that The North Briton has stopped being published.

The Ugliest Man in Britain Takes on the King

Suddenly, on April 23, 1763, a new version of a publication called “The North Briton No. 45” (which was named after the Jacobite rebellion) was released. This publication strongly criticized a speech made by King George III, where he supported a peace plan called the Paris Peace Plan that marked the end of a war called the Seven Years’ War (which was known as The French and Indian War in the American colonies). Wilkes, the publication’s author, was critical of the King because he believed Bute wrote the speech. In addition, Wilkes was unhappy because he thought Bute was too kind towards the French.

“Is Bute’s influence really at an end, or does he still govern by the three wretched tools of his power?” he asks.

“A despotic Minister will always endeavor to dazzle the prince with high-flown ideas of the prerogative and honor of the Crown. I wish as any man to see the honor of the Crown maintained in a manner truly becoming royalty. I lament to see it sunk even to prostitution.”

The King was very angry when he read it. He was so mad that he ordered the police to arrest anyone connected to the paper. Because of this, Wilkes and forty-eight other people were taken into custody.

During his court hearing, Wilkes claimed parliamentary privilege, a legal safeguard that protects members of Parliament against legal consequences for their actions or statements during legislative duties. The judge agreed with Wilkes, and as a result, he was released and allowed to resume his position in Parliament. However, Parliament swiftly voted to eliminate the immunity for members of Parliament regarding arrest for writing and publishing seditious libel.

Feeling very confident, Wilkes decides to take things further by writing and sharing a very explicit poem called “An Essay on Women.” He dedicates this poem to Fanny Miller, who is in a relationship with John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich. The Earl, to criticize Wilkes’ actions, reads the poem aloud in the House of Lords. The House of Lords members find the poem offensive and disrespectful to religion and vote to remove Wilkes from Parliament.

He escapes to Paris before the trial and is forced to leave to heal from an injury he got in a duel with Samuel Martin Martin. Wilkes believed it was an assassination attempt by the government. However, Martin was angry about how he was portrayed in No. 40: “the most untrustworthy, despicable, selfish, low, and dishonorable person who ever managed to become a Secretary.”

Wilkes was found guilty in absentia and declared an outlaw on January 19, 1764.

After getting better from the injuries caused by the duel, Wilkes decides to remain in France. Later on, he relocates to Italy. During this period, he leads a lavish and morally questionable lifestyle, indulging in extravagant spending and relationships with women such as Gertrude Corradini, a famous 19-year-old Italian opera singer. Meanwhile, he seeks pardon for his actions but consistently rejects his requests to reconcile.

After running out of money, Wilkes went back to London in 1768. He was punished with a fine of £1000 and received a jail sentence of twenty-two months for the crimes he was found guilty of in 1764. Additionally, despite winning a seat for Middlesex, he was expelled from Parliament.

Massacre of St. George’s Field

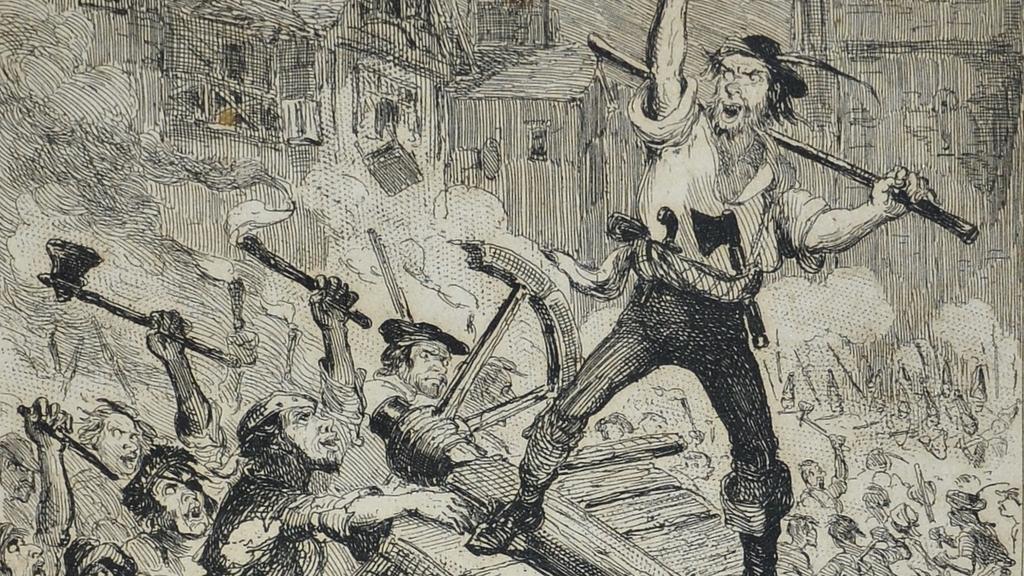

On May 10, 1768, 15,000 Wilkes supporters marched to the prison where he was held, chanting, ‘Wilkes and Freedom!’ and ‘Down with the King!’

The protest quickly turned into a riot. The government deployed the Grenadier Guards on horseback to restore order, marking the first time in history that the ‘Riot Act’ was officially read. But instead of calming the crowd, tensions escalated. Soldiers, pelted with stones, responded by opening fire—killing an unknown number of protesters.

Shortly after that, the rioters dispersed, but the violent outbreak among the people spread throughout London when news spread about the deaths at St. George’s Field. The lives of the King and the Queen were at risk. Gossip started circulating that even the King might give up his position. In the end, the situation calmed down. However, Wilkes still posed a threat to the government.

The Ugliest Man in Britain Wins Parliament—Even From Jail!

While Wilkes was in jail, he was elected to Parliament multiple times. However, he was kicked out each time – first on February 3, 1769, then on February 16, again on March 16, and finally on April 13, 1769.

After the fourth election, Parliament declared his opponent the winner, which made Wilkes even more popular. Angry and upset, his followers once again went out on the streets, loudly shouting, “Wilkes and Liberty!” The same chant was heard in America when Wilkes was released in 1770.

The Legacy of the Ugliest Man in Britain in America

In 1771, Wilkes continued his fight against the Crown by being chosen as the Sheriff of London for one year. Then, in 1774, he was elected as the Lord Mayor of London for one year. In the same year, he was elected to Parliament and was allowed to serve this time. He remained a member of Parliament for the next sixteen years, where he opposed the war against the American colonies and fought for freedom of the press and religious tolerance. Finally, in 1779, he was elected as the Chamberlain of the City of London, a powerful role he held until his death on December 26, 1797. He is buried in The Grosvenor Chapel, South Audley Street, Mayfair, London.

Wilkes’ Ghost

In 1927, the Reverend Francis Underhill, who later became the Bishop of Bath and Wells, and his Assistant Priest at the Grosvenor Chapel experienced a strange feeling in the corner of the Chapel close to Wilkes’ memorial tablet. They invited a lady with psychic abilities who described seeing a figure with “two horns growing back from his head, like a devil.” Upon further investigation, she concluded that it was John Wilkes. In 1956, another person claimed to have felt Wilkes’ presence near a house next to the Chapel.

American counties, towns, and streets named after Wilkes

Wilkes was well-liked in America because he fought against the British government, particularly the corrupt ministries of George III. As a result, many places in the United States were named after him, such as Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania (named after him and another member of Parliament, Isaac Barre, who coined the phrase the “Sons of Liberty”). There are also Wilkes Counties in Georgia and North Carolina, both named after him.

In 1796, Alexandria grew towards Great Hunting Creek in the south, West Street in the west, and Montgomery Street in the north. Six new streets were built, including Wilkes Street, named after John Wilkes. Today, the street starts at the Harbor Place townhomes by the Potomac River, goes through the Wilkes Street Tunnel and “the bottoms,” and ends at South Columbus Street. From there, it becomes a path for walking and biking until it reaches S. Patrick Street (Route 1). Once it crosses Route 1, it becomes a street for vehicles again and continues west for a few blocks until it ends at the Alexandria National Cemetery on Wilkes Street (1450). The Alexandria National Cemetery is one of thirteen Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex cemeteries.

Notable Decedents

Charles Wilkes

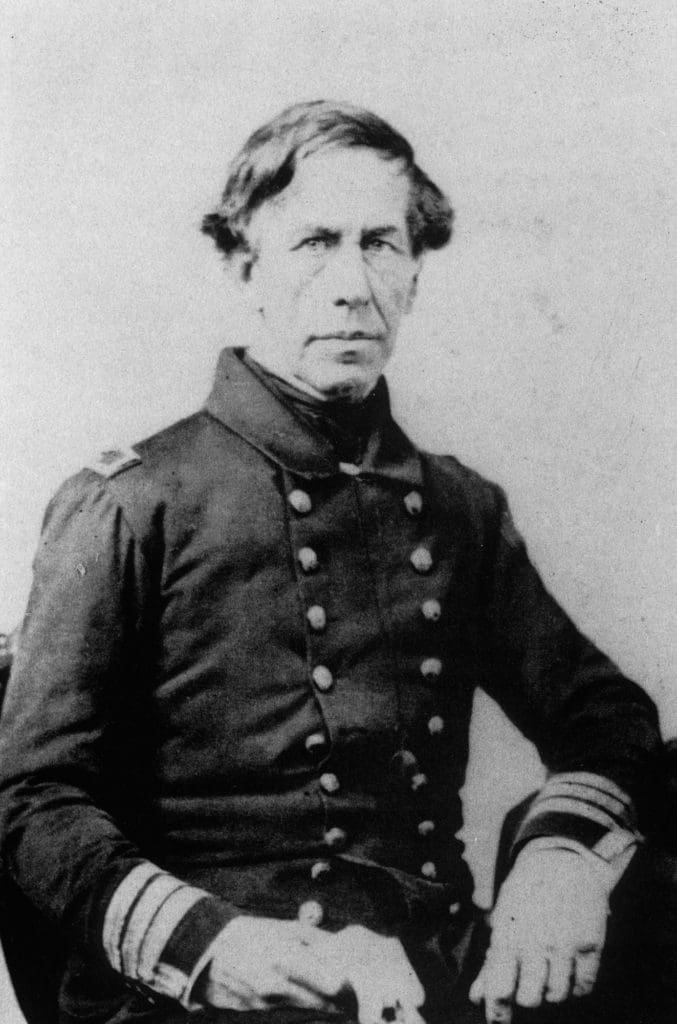

Great Nephew Charles Wilkes was a famous American navy officer and explorer who found Antarctica on January 19, 1840. He was born on April 3, 1798, in New York City. His mother was Mary Seaton, who died when Charles was three. He was then sent to live with his aunt Elizabeth Anne Seaton, who was later recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

Wilkes joined the Navy in 1818 and rose to the rank of Lieutenant in 1826.

In 1841, he traveled along the west coast of North America, discovering places like The Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Puget Sound. He got caught in a storm during one of his journeys in a small boat called a captain’s gig. Luckily, he found a safe place to take shelter in a small inlet. This inlet was later named Gig Harbor and is now a charming village in Pierce County, Washington.

Wilkes was also in charge of the steam frigate USS San Jacinto (1850) that captured the HMS Trent and two Confederate Commissioners, James Mason – who is buried in Christ Church Cemetery – and John Slidell as contraband of war, on November 8, 1861, which was a severe violation of international law.

“The actions of The Notorious Wilkes, as the Bermuda media called him, went against maritime law and made many people believe that a big war between the United States and England was going to happen.”

Congress expressed its gratitude to Wilkes for his courageous act. However, Lincoln recognized the challenge of being engaged in two conflicts simultaneously. Consequently, he discreetly released Mason and Slidell from Fort Warren in Boston and allowed them to depart.

Wilkes, who was controversial and tough, continued his career in the US Navy and passed away as a Rear Admiral in 1909. He is laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery, which was established in 1864 because the Soldiers Cemetery on Wilkes Street – named after his great uncle – in Alexandria had no space left for more burials. On his tombstone, it is written, “He Found the Ant-Arctic Continent on January 19, 1840!”

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth, who killed President Abraham Lincoln, was related to Wilkes through his great-grandmother Elizabeth Wilkes.

Beyond Appearance: The Lasting Legacy of the Ugliest Man in Britain

Though remembered as the Ugliest Man in Britain, John Wilkes left behind a legacy far greater than his looks. He fought for free speech, challenged the monarchy, and became a symbol of rebellion—so much so that his name still echoes across towns, streets, and counties in the United States.

Centuries later, his story reminds us that wit, courage, and ideas can outshine even the harshest first impressions

Sources of Information

Roberts, A. (2021). The last king of America: The misunderstood reign of George III. Viking.

Smith, G. (1992). American Gothic: The story of America’s legendary theatrical family, Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth. Simon & Schuster.

Thomas, P. D. G. (1996). John Wilkes: A friend to liberty. Oxford University Press.

Trench, C. C. (1962). Portrait of a patriot: A biography of John Wilkes. William Blackwood & Sons Ltd.

Unger, H. G. (2017). First founding father: Richard Henry Lee and the call to independence. Da Capo Press.