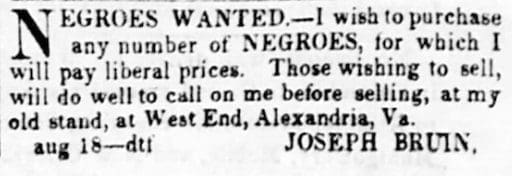

In Alexandria’s Methodist Protestant Cemetery rests Joseph Bruin (1808 – 1882), a prominent figure known for his involvement in the slave trade. He ran one of the largest slave pens in Alexandria during his time. In 1844, Bruin acquired a brick Federal-style building located at 1707 Duke Street, along with adjacent acreage, to use as his slave jail.

The slave pen served as a holding facility for enslaved people who were being bought and sold. It was a place of immense suffering and hardship for those imprisoned there, waiting to be sold to new owners or transported to other locations.

It is essential to recognize and remember this dark chapter of history, highlighting the inhumane treatment and exploitation of enslaved individuals during the antebellum era. The existence of such places underscores the need to confront the legacy of slavery and continue working toward a more just and equitable society.

In response to claims that “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was merely fictional and not reflective of real events, Harriet Beecher Stowe published “The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Presenting the Original Facts and Documents Upon Which the Story Is Founded” in 1854. In this follow-up work, Stowe provided evidence to support the authenticity of her novel, effectively countering the accusations of falsehood. 1

Within “The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” the Bruin slave jail in Alexandria is mentioned multiple times. Operated by Joseph Bruin, a slave dealer, this infamous facility held enslaved individuals before their sale, subjecting them to horrific conditions.

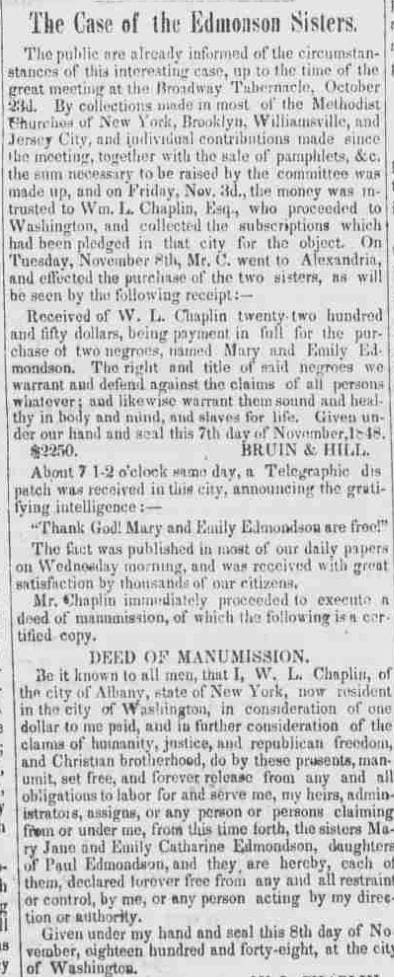

Chapter Six recounts the inspiring story of the schooner Pearl, where fugitive slaves attempted to escape from Washington to New Jersey for freedom. Among the escapees were six children from the Edmonson family and their mother, Amelia. The story of sisters Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson (1835–1895) garnered widespread attention, stirring emotions across the nation in 1848.

The fate planned for the Edmonson sisters, who were to be sold as “fancy girls” for sexual exploitation, eerily parallels the fictional character Emmeline’s fate in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The novel’s cruel plantation owner, Simon Legree, purchased Emmeline to use as a sex slave, replacing his previous sex slave, Cassy. The experiences of the Edmonson sisters serve to underscore the grim realities of slavery that Stowe sought to reveal.

The harrowing tale of the Edmonson sisters and Stowe’s influential literary work helped fuel the growing anti-slavery sentiment in the United States, adding momentum to the call for abolition. Their courageous journey and the publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” stand as pivotal moments in the fight for justice and equality in American history, demonstrating the power of storytelling to bring attention to social injustices and inspire change.

The Edmonson Family

The Edmonson family led a relatively comfortable life on a forty-acre farm located in Norbeck, near Silver Spring, Maryland. Their farm produced crops such as corn and oats, and they also raised cows and pigs. Paul Edmonson, the head of the family, was a free Black man. However, his wife, Amelia, was not fortunate enough to be free. Under the prevailing law at that time, if a mother was enslaved, all her children would also be considered enslaved, regardless of their father’s status or race. This unjust law denied the children of enslaved Black women access to their father’s rights and freedom.

Ownership of Amelia and her children rested with a woman named Rebecca Culver, who was mentally incompetent or “touched,” as it was described. As a result, her brother-in-law, Francis Valdenar, was appointed to manage her estate, which included the Edmonson family, who were held in bondage. Valdenar allowed Amelia and her children to remain on the farm until the children reached an age at which they could be hired out for work. Typically, this occurred when they were around thirteen years old, which was a common practice that provided income for their enslavers.

Paul Edmonson had managed to purchase the freedom of four older girls in the family. However, when he attempted to buy the freedom of others, including his daughters Mary and Emily, Valdenar refused to allow it. As a result, Mary, at the age of 15, and her 13-year-old sister Emily were sent to work in private homes in Washington. Their separation from their family and their forced labor in unfamiliar environments were common occurrences during that dark period of history, highlighting the heart-wrenching reality faced by enslaved families.

The story of the Edmonson family serves as a poignant example of the injustices and hardships endured by enslaved individuals and families during a time when human rights were disregarded based on race and enslavement. The struggle for freedom and the fight against such oppressive systems would eventually become part of the broader movement to abolish slavery and secure civil rights for all.

The “Pearl” Incident

On the night of April 15, 1848, the Edmonson family, consisting of the girls Mary and Emily and their brothers Samuel, Ephraim, Richard, and John, along with their mother Amelia, embarked on a daring attempt to escape to freedom. They were part of a group of over seventy individuals seeking liberty on a fifty-four-ton schooner called the Pearl. Abolitionists, possibly including the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, had organized the escape plan.

The Pearl was meant to carry them on a perilous journey. They planned to sail the schooner down the Potomac River, then up the Chesapeake Bay, and onward through the Delaware River to reach New Jersey, where they hoped to find sanctuary from slavery.

However, their hopes were tragically dashed when, two days after departing from Washington, the Pearl was intercepted on the Chesapeake Bay near Point Lookout, Maryland. 35 armed men, led by Joseph Bruin, had chased after the schooner using a steamship named the Salem. The armed men overtook the Pearl, and everyone on board, including the Edmonson family, was captured and detained.

The failed escape attempt was a devastating setback for the Edmonson family and their fellow fugitives. It also shed light on the dangerous risks enslaved individuals and abolitionists faced when trying to escape the brutal bonds of slavery. Nonetheless, this event, along with other attempts at escape and the abolitionist movement, played a crucial role in raising awareness about the cruelty of slavery and fueled the efforts to end this abhorrent practice in the United States.

A Sense of Celebration filled the Air

Upon hearing the news of the recapture of the Pearl and its fugitives, a sense of celebration filled the air. The atmosphere turned festive as the Pearl, accompanied by the steamship Salem, was towed back upriver. The recaptured escapees and the ships carrying them became a spectacle, drawing attention from both the captors and the onlookers.

As the two boats passed through Alexandria on the morning of Tuesday, April 18, the town’s residents gathered along the shore and crowded the docks. They were eager to witness the sight of the captured fugitives and the vessels that thwarted their attempt at freedom. Instead of feeling sympathy for those who had tried to escape enslavement, the townspeople expressed jubilation at the failure of the escape.

Cheers rang out from the shoreline, demonstrating the prevailing sentiment of many in the town who supported the institution of slavery and opposed any efforts to challenge it. The sight of the captives being brought back to Washington was seen as a triumph for the pro-slavery forces in the region.

This event highlighted the stark contrast in attitudes towards slavery, with some supporting the abolitionist cause and others vehemently defending the institution. It served as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted divisions in American society over the issue of slavery and the ongoing struggle for freedom and human rights during that tumultuous period in history. 2

Bruin Rejects Pleas to Negotiate the Sister’s Freedom

In the aftermath of the recapture of Pearl’s fugitives, the fate of those who were caught posed a dire threat: they were likely to be “sold South,” a term referring to the practice of sending enslaved individuals to the Deep South states, where the conditions were even harsher and escape opportunities were minimal. In response to this impending tragedy, friends and family of the recaptured individuals, including the Edmonson family, made valiant efforts to save their loved ones by purchasing their freedom.

Joseph Bruin, who operated a significant slave warehouse in Alexandria, saw an opportunity to profit from the situation. He offered four thousand five hundred dollars for the six Edmonson children, who were then transferred to his slave pen located at 1707 Duke Street. Despite the pleas and attempts made by their friends and supporters to negotiate for their freedom, Bruin was obstinate and rejected any terms proposed to him.

Even when a kind-hearted lady with whom Mary Edmonson had previously lived offered a thousand dollars for Mary alone in an attempt to save her from the grim fate awaiting her in the South, Bruin callously refused the offer. He insisted that he could fetch a much higher price for her in the New Orleans slave market, indicating that he had long had his eye on the Edmonson family and had been waiting for the opportunity to profit from their sale.

Bruin’s actions exemplify the cruel and exploitative nature of the slave trade during that era, where human lives were treated as mere commodities to be bought, sold, and disposed of for profit. The desperate attempts of friends and family to save their loved ones, coupled with the unyielding greed of individuals like Bruin, emphasize the tragic and heartrending consequences of a society deeply entrenched in the dehumanizing institution of slavery.

The New Orleans Slave Auction Blocks

According to Harriet Beecher Stowe, even Joseph Bruin’s daughter pleaded with him to spare Mary and Emily Edmonson from being sent to New Orleans, but Bruin remained unyielding. In early May 1848, he orchestrated their transfer, along with their brothers and 28 other Pearl fugitives, via the packet ship Union, which departed from Baltimore.

During the voyage, the Union encountered inclement weather, leading to shortages of food and water and the subsequent reduction of rations for everyone on board. Nearing the mouth of the Mississippi River, a fierce storm battered the ship, veering it off course and almost causing its destruction. Despite these challenges, the Union finally reached New Orleans after an arduous 20-day journey, a fact reported in The New Orleans Crescent on June 14, 1848.

Upon arrival, the enslaved individuals were taken to a slave pen, awaiting sale. The plan for the Edmonson sisters was particularly harrowing, as they were to be sold as “fancy girls,” a term denoting female slaves held mainly for sexual exploitation. This news outraged Northern abolitionists, especially considering that the sisters were devout Methodists. Abolitionist figures like Reverend Henry Ward Beecher organized rallies to raise funds to buy the sisters’ freedom.

Fortuitously, the sisters were reunited with their long-lost brother Hamilton in New Orleans. Having bought his freedom and become a skilled cooper, Hamilton, who had connections in the city, did his best to care for his sisters during their captivity.

Meanwhile, Northern abolitionists’ fundraising efforts persisted. A yellow fever outbreak in New Orleans gave Joseph Bruin a pretext to return the sisters to Washington.

The Edmonson sisters’ story symbolizes the courage and resilience of those seeking freedom from slavery’s horrors and the relentless determination of abolitionists to combat this inhumane institution. Their tale also illuminates the profound humanitarian crisis engendered by treating people as property, emphasizing the dire need for abolition and acknowledgment of every individual’s inherent dignity and value.

The Return to Bruin’s Slave Pen

After being sent back to Washington, the Edmonson sisters, Mary and Emily, found themselves once again imprisoned in Joseph Bruin’s Duke Street slave pen. There, they endured an excruciating eight-month wait while Northern abolitionists fervently worked to raise the necessary funds to buy their freedom. Bruin eventually agreed to a price of $2250.

During this period of captivity, Bruin tormented the sisters with threats, repeatedly warning them that if the required sum was not raised promptly, he would send them back to New Orleans to be sold into prostitution. This cruel tactic was an evident attempt to pressure the abolitionists into hastening their efforts to accumulate the needed funds.

Finally Free!

Finally, on November 7, 1848, the efforts of the Northern abolitionists proved successful, and the required payment was made to Bruin. The following day, November 8, 1848, Mary and Emily Edmonson were finally set free from their shackles and released from the oppressive grip of slavery. They were relieved from their ordeal and ready to begin a new chapter in their lives.

After gaining their freedom, the sisters moved to New York, where they could embrace a life of liberty and independence. Their journey to freedom, marked by perseverance and the unwavering support of abolitionists, showcased the power of collective action and highlighted the importance of the abolitionist movement in challenging the institution of slavery.

The story of Mary and Emily Edmonson is a testament to the courage and resilience of those who fought for freedom and justice during a dark period in American history. Their emancipation is a reminder of the progress made in the fight against slavery and the ongoing struggle for equality and human rights.

Protesting the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

After Mary and Emily Edmonson gained their freedom, they had the opportunity to pursue education, and they enrolled in New York Central College. During their time at the college, they became passionate advocates against the proposed Fugitive Slave Act. This act was sponsored by Virginia Senator James Murray Mason, who is buried in the Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Senator Mason introduced the Fugitive Slave Act as a response to his outrage over another proposed act that aimed to outlaw the sale of slaves in Washington, D.C. This proposal arose as a direct consequence of the Pearl incident, which involved the sisters and others attempting to escape slavery on the schooner Pearl. Both of these acts were ultimately passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, a set of legislative measures intended to address the ongoing tensions between slave and free states.

The Fugitive Slave Act was a particularly controversial provision of the Compromise of 1850. It strengthened the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, making it easier for slaveowners to reclaim fugitive slaves who had escaped to free states. This act sparked outrage among abolitionists and further exacerbated the divide between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the country.

Mary and Emily Edmonson, having experienced the horrors of slavery firsthand, recognized the importance of opposing such legislation that perpetuated the system of enslavement and denied basic human rights to those seeking freedom. By speaking out and protesting against the Fugitive Slave Act, they joined the ranks of many other abolitionists who were dedicated to fighting against the institution of slavery and advocating for the rights and dignity of all individuals.

Mary dies from Tuberculosis

In 1853, Mary and Emily Edmonson enrolled in Bowen College in Oberlin, Ohio, eager to pursue their education and build a better future. Tragically, their hopes were shattered when, within six months of their enrollment, Mary fell ill and succumbed to “pulmonary consumption,” which is now known as Tuberculosis. She passed away on May 18, 1853, at the young age of twenty.

Devastated by the loss of their beloved sister, Emily and the rest of their family laid Mary to rest in Oberlin’s Westwood cemetery, where they paid their final respects. However, over time, Mary’s grave was lost, and her final resting place remains unknown.

Mary’s premature death marked a poignant reminder of the harsh toll that slavery and its aftermath took on individuals and families. Her aspirations for education and a better life were cut short, leaving her loved ones to carry on her memory and continue the fight for justice and equality. Though her grave may be lost, the legacy of Mary Edmonson and her courageous pursuit of freedom and education continues to inspire and resonate with those who value the inherent worth and potential of every human being.

Emily Continues the Work

In 1860, Emily Edmonson married Larkin Johnson (1815 – February 26, 1885), and together, they embarked on a life together. They eventually settled in a home near the residence of Frederick Douglass (February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) in Washington, D.C. Emily remained steadfast in her commitment to working for the rights and advancement of African Americans.

After a life dedicated to advocating for the rights of her community, Emily passed away on September 5, 1895. She was laid to rest near her husband in Hillsdale Cemetery, located in Southeast Washington, D.C.

However, in March 1967, a decision was made to disinter all the individuals buried in Hillsdale Cemetery. Emily’s remains, along with others, were re-interred in a city plot at either Blue Plains or Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland. This event marked the end of the original cemetery’s existence, but the memory of Emily Edmonson’s efforts and contributions to the cause of African American rights continue to be remembered and honored by those who recognize the significance of her legacy.

The Fate of Joseph Bruin

Bruin continued his business of selling slaves until the Civil War.

Joseph Bruin persisted in his slave trading business until the outbreak of the Civil War. When the war commenced, he fled Alexandria in an attempt to avoid the repercussions of his actions. However, he was eventually captured and confined to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., where he remained throughout the duration of the war. The Old Capitol Prison, which had previously served as the temporary Capitol of the United States from 1815 to 1819, was later demolished in 1929, and the U.S. Supreme Court building now occupies the site.

In the meantime, Bruin’s slave jail took on a new role as the Fairfax County Courthouse until July 1865. This building played a significant role in the local administration of justice during the tumultuous period of the Civil War.

Joseph Bruin passed away in 1882 and was laid to rest in the Methodist Protestant Cemetery, which is part of the Wilkes Street Complex in Alexandria. His wife, Martha Helen Rust, joined him in the family plot upon her death in 1887. Many other members of the Bruin family were also interred in the same cemetery, creating a lasting legacy for generations to come.

The story of Joseph Bruin and his involvement in the slave trade is a sobering reminder of the deep scars left by the institution of slavery in American history. His life and actions underscore the importance of acknowledging and confronting this dark chapter in our past while striving for a more just and equitable society today.

| JOSEPH BRUIN 1809 – 1882 MARTHA H. BRUIN 1821 – 1887 MATTIE BRUIN ADAM 1844 – 1898 JOSPEHINE BRUIN 1848 – 1932 BRUIN HELEN MAY BRUIN 1862 – 1868 J. WILLIAM BRUIN 1877 – 1878 S. SOPHENIA BRUIN 1842 – 1843 J. EDWARD BRUIN 1856 – 1882 |

The Emancipation Proclamation, Juneteenth, and the 13th Amendment

On April 16, 1862, a significant moment in the fight against slavery occurred when President Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act. This landmark legislation brought an end to slavery in Washington, D.C., and granted freedom to more than 3,000 enslaved individuals.

Another crucial step towards freedom for enslaved individuals came on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This historic proclamation declared the emancipation of enslaved individuals in the territories that were still in rebellion against the Union during the American Civil War.

On June 19, 1865, U.S. Army General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, and delivered the momentous news that the Civil War had ended and, with it, the institution of slavery. Although slavery was officially abolished through the Emancipation Proclamation, it had not yet reached certain states like Kentucky, Delaware, and New Jersey, which had remained loyal to the Union during the war. June 19th, now known as Juneteenth, has since become a day of celebration in the United States, commemorating the emancipation of enslaved individuals.

The culmination of these efforts came with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 6, 1865. This amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime, in the entire United States. This momentous amendment signified a historic turning point in American history, forever ending the abhorrent practice of slavery in the nation.

These events collectively reflect the tireless efforts and sacrifices abolitionists, leaders, and enslaved individuals made in their quest for freedom and equality. The path to emancipation was long and arduous, but it marked a significant milestone in building a more just and inclusive society.

Sources of Information

Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Boston. Jewett Publishing. 1854.

Mary Kay Ricks. Escape on the Pearl. The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad. Harper Collins Publishers. New York, New York. 2007.

William Yoo. What Kind of Christianity? A History of Slavery and Anti-Black Racism in the Presbyterian Church. Westminster John Knox Press. Louisville, Kentucky. 2022.

Rachel L. Swarns. The 272. The Families Who Were Enslaved And Sold to Build the American Catholic Church. Random House. New York, NY. 2023.

The official website of the National Park Service includes a webpage about the Bruin Slave Jail. The page was accessed in 2022.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly (1852) sold 300,000 copies in the United States and 1,000,000 copies in Britain within its first year of publication, becoming the second best-selling book of the nineteenth century after the Bible. ↩︎

- Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl. The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Road Railroad. Harpers Collins Publishers. New York, NY. 2007. P. 84. ↩︎