Introduction

On August 1, 1803, Alexandria, Virginia—a thriving port city of 6,000 souls—faced one of the most devastating crises in its history. A yellow fever epidemic descended upon the town, leaving in its wake a trail of death, fear, and, ultimately, transformation. This tragic event would lead to the creation of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, a historic burial ground that tells the story of Alexandria’s resilience and evolution.

Yellow Fever: The Catalyst for Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

Yellow fever was one of early America’s most dreaded diseases. Transmitted by infected female mosquitoes—a fact unknown to the populace at the time—the disease manifested with gruesome symptoms: severe backaches, high fevers, chills, nausea, and telltale jaundice that gave the illness its name. For many, the initial bout was just the beginning. A relapse often followed, viciously attacking the kidneys and liver, frequently resulting in death.

Crisis in Alexandria: Setting the Stage for New Burial Grounds

The epidemic’s impact on Alexandria was catastrophic:

- Half of the city’s 6,000 inhabitants fled in panic to nearby farms and family plantations.

- Of the 3,000 who remained, 1,000 fell ill.

- The mortality rate among the infected was a staggering 20%.

Alexandria ground to a halt. Its usually bustling streets fell silent, save for the grim morning ritual of horse-drawn carts collecting the night’s dead.

Medical Challenges Leading to Wilkes Street Cemetery’s Creation

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick, Alexandria’s Superintendent of Yellow Fever, grappled with the outbreak. Ironically, Dr. Dick—who had been present at George Washington’s deathbed just four years earlier—misattributed the epidemic’s cause to “kiln-heated oyster shells with putrid fish.” This misconception highlights the limited medical knowledge of the time, despite Dr. Dick’s reputation as one of Alexandria’s most prominent physicians.

Sacred Ground: The Toll That Shaped Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

As deaths mounted, Alexandria’s graveyards were quickly overwhelmed. Dr. James Muir, pastor of the Presbyterian Meeting House, delivered a poignant sermon titled “Death Abolished” in late fall, summarizing the grim toll.

Dr. Muir’s sermon provided the following tragic statistics:

- Penny Hill Cemetery: 120 interments

- Christ Church Episcopal burial ground: 41 interments

- Presbyterian Meeting House burial ground: 14 interments

- New Fairfax Street burial ground: Approximately 10 interments

- Quaker and St. Mary’s Cemetery (now known as Saint Mary’s Catholic Cemetery and Queen of Heaven Columbarium): About 3 interments each.

In total, 191 souls were laid to rest within a few short months—a staggering number for the small town.

Alexandria’s Evolving Burial Practices: The Wilkes Street Solution

The story of Alexandria’s cemeteries and the future Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex began before the 1803 epidemic. In 1796, the municipal cemetery known as Penny Hill was relocated to an area outside the town’s core, which would later become part of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex. This move, predating the epidemic by seven years, inadvertently positioned Penny Hill to play a crucial role during the crisis.

When yellow fever struck in 1803, Penny Hill, already situated away from the town center, bore the brunt of the epidemic’s toll. Its location aligned with growing concerns about public health and burials within town limits.

The 1804 Edict: Birthing the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

The epidemic’s devastation prompted swift action from city leaders. Fearing contamination of the town’s wells from decomposing bodies, the Alexandria town council (then part of the District of Columbia) issued a crucial decree in March 1804: no new graves could be dug within the corporation limits.

This edict catalyzed a significant shift in Alexandria’s approach to burials. It led to new burial grounds in the 82-acre Spring Garden Farm, located in Fairfax County, Virginia, near the already-established Penny Hill cemetery.

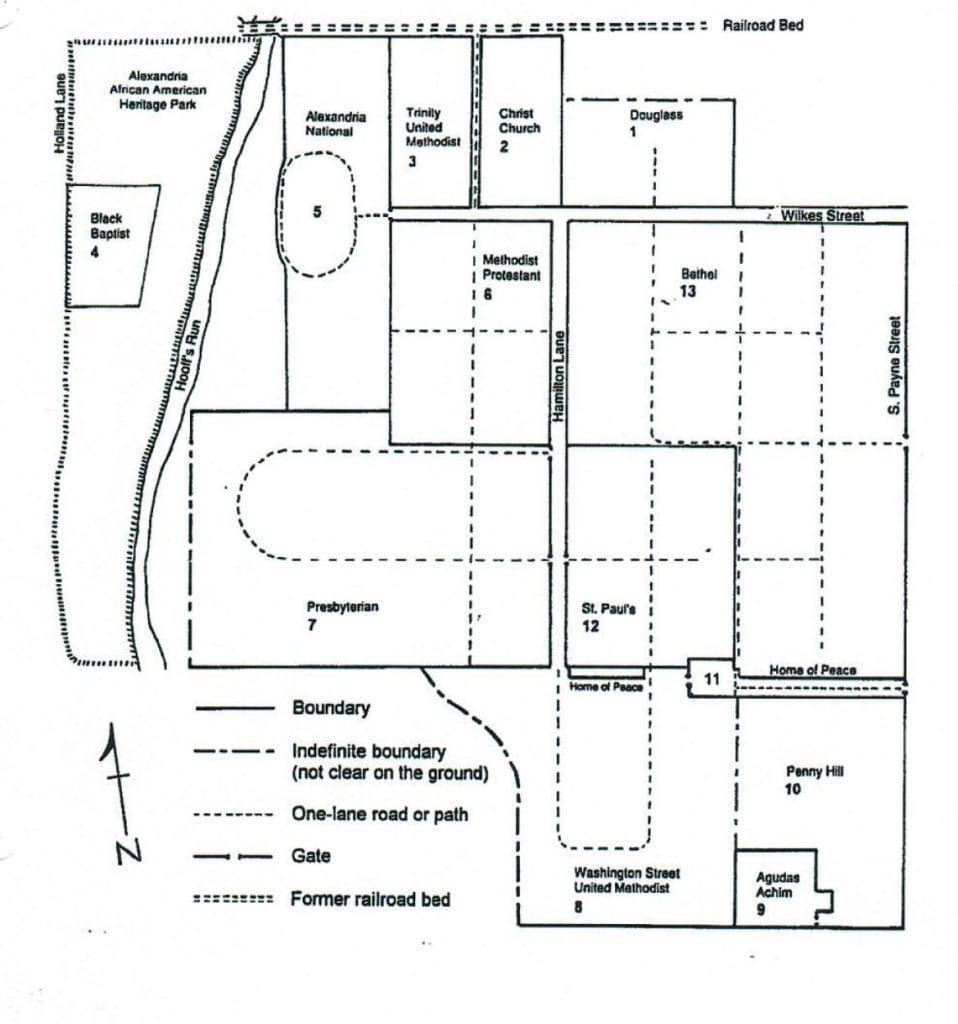

This decree not only changed Alexandria’s approach to burials but also set the stage for creating what would become one of the most significant historic cemetery complexes in the United States. The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, comprising 13 separate cemeteries, is considered by some historians to be the most historically diverse and significant cemetery complex in the nation. Its varied grounds reflect Alexandria’s social, cultural, and demographic evolution over two centuries.

Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex: Birth and Evolution

The area that would become the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex began with Penny Hill, which was relocated to this site in 1796. Following the 1804 edict, the complex grew and evolved over more than a century:

1. Early 19th Century: In-town churches establish new cemeteries

- Presbyterian Cemetery

- Trinity Methodist Church Cemetery

- Christ Church (Episcopal) Cemetery

- St. Paul’s Episcopal Cemetery (a breakaway congregation from Christ Church)

2. Mid-19th Century: New denominations and populations represented

- 1833: Methodist Protestant Church Cemetery (a breakaway congregation from Trinity)

- 1857: Home of Peace Cemetery (the first Jewish cemetery in Virginia)

- 1860: Union Cemetery (established by Washington Street United Methodist, another breakaway Methodist congregation)

3. Civil War Era

- 1862: Alexandria National Cemetery (the first national cemetery established under a Congressional Act of July 1862 during the Civil War)

4. Late 19th to Early 20th Century: Burial societies and community cemeteries

- 1885: Bethel Cemetery and a Black Baptist Cemetery

- 1895: The Douglas Cemetery

- 1933: Agudas Achim Cemetery

These historic cemeteries within the Wilkes Street Complex reflect the changing face of Alexandria over time.

Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex: A Tapestry of Alexandria’s History

This chronological development of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex reflects Alexandria’s growing diversity and changing demographics. From the initial response to the Yellow Fever epidemic to establishing denominational, ethnic, and national cemeteries, the complex tells a rich story of Alexandria’s evolution as a community.

Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex: Modern Significance and Legacy

In 1915, a significant change occurred when Alexandria annexed over 1,300 acres from Fairfax County, bringing the cemetery complex officially within city limits. Today, the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex is a testament to Alexandria’s resilience and diversity. It comprises 13 separate cemeteries, housing an impressive 35,000 burials. Each cemetery and gravestone tells a story, from the victims of the 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic to Civil War soldiers and from early Jewish settlers to Alexandria’s African American community.

This 1933 map of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, found in Greenly’s comprehensive study of Alexandria’s cemeteries (1996, p. 26), showcases the layout of the 13 separate cemeteries shortly after Alexandria annexed the area. It visually represents how the complex evolved from its origins during the 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic to become a diverse collection of burial grounds reflecting Alexandria’s rich cultural tapestry.

As we reflect on the complex’s journey from a response to crisis to a diverse historical landmark, we see how the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex embodies Alexandria’s growth, challenges, and triumphs over the past two centuries.

Visitors today can trace the impact of the 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic through the oldest gravestones in the complex.

Conclusion: A City Forever Changed

From its origins in the aftermath of the 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic to its status today as a collection of historic cemeteries, the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex encapsulates over 200 years of Alexandria’s history. Born out of crisis, this vital historical resource has become far more than a final resting place for generations of Alexandrians.

The complex is a testament to Alexandria’s evolution, chronicling the city’s religious, ethnic, and social transformation from a small port town to a diverse urban center. Each of its 13 cemeteries tells a unique story, collectively weaving a rich tapestry of cultural heritage and community resilience.

As we walk through these historic grounds today, we’re reminded of the enduring spirit of those who came before us. Their response to the Yellow Fever crisis honored their dead and laid the foundation for the Alexandria we know today. The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex serves as a poignant reminder of how a community’s response to tragedy can shape its future for centuries.

Call to Action

Experience the powerful legacy of Alexandria’s 1803 Yellow Fever epidemic and trace the city’s evolution through the centuries at the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex. From the crisis that reshaped burial practices to the diverse communities that found their final resting place here, each gravestone tells a unique story of resilience, change, and community spirit. Join one of our guided tours to walk in the footsteps of history – from epidemic victims and Civil War soldiers to early Jewish settlers and prominent African American citizens. Discover how a public health crisis gave birth to a rich tapestry of Alexandria’s cultural heritage. Visit Gravestone Stories to book your journey through time and experience firsthand the remarkable history etched in stone at the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Sources of Information

Alexandria Association. (1956). Our town, 1749-1865: Likenesses of this Place & its People taken from life by artists known and unknown [Pamphlet]. Gadsby’s Tavern.

City of Alexandria. (n.d.). Information on cemeteries. [Official Website].

Gardner, W. M., Snyder, K. A., Hurst, G., Walker, J. M., & Mullen, J. P. (1999). Excavations at the Old Town Village site, corner of Duke and Henry Streets, Alexandria, Virginia: An historical and archeological trek through the 200-year history of the original Spring Garden development. Eakin and Younentob.

Greenly, M. (1996). Those Upon the Curtain Has Fallen: The Past and Present Cemeteries of Alexandria, VA. Alexandria Archaeology Publications.

Muir, J. (1803). Death abolished: A sermon, occasioned by the sickness which prevailed at Alexandria during August, September, and October, giving detail of that sickness and some of the views of Providence in such calamitous visitations. With an appendix containing facts relating to the origin of the sickness – the extent of the morality – the labors of the committee of health, and the contributions to the relief of the poor. Cotton and Stewart.

Old Presbyterian Meeting House. (n.d.). [Portrait painting of Dr. James Muir]