The only surviving record of the Liberia constitutional convention lies in the journal of a man buried in Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex

A Grave with International Significance

Walk through Trinity Methodist Cemetery in Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, and you’ll encounter a weathered gravestone featuring the carved image of an open book. Most visitors pass by without a second glance. But this grave holds the remains of Dr. James Washington Lugenbeel—the only person who documented the Liberia constitutional convention that created Africa’s first independent republic.

On July 26, 1847, Liberia adopted its constitution and declared independence. Dr. Lugenbeel was there, keeping a detailed journal of the proceedings. Without his chronicle, historians would have the final constitutional text but no understanding of the debates, arguments, and compromises that shaped it.

His journal remains the sole window into how formerly enslaved people and their descendants deliberated to create a constitutional democracy in Africa.

And he’s buried right here in Alexandria.

The Man Behind the Journal

Early Life and Education

Born in Virginia in 1819 to Moses Lugenbeel and Ari McDaniel, James Washington Lugenbeel pursued medicine at a time when few Americans received formal medical training. He graduated from Columbian University (now George Washington University) in Washington, D.C. in 1841, positioning himself at the forefront of 19th-century medical practice.

On July 25, 1846, he married Martha Alice Abercrombie (1818-1891) in Alexandria. Their only child, daughter Emily, was born the following year. The young family lived with Martha’s mother, Susan Davy (1795-1870), and stepfather, Thomas Davy, in Alexandria, where the Davy household provided stability as Lugenbeel traveled to and from Liberia for his medical work.

Appointment to Liberia

In 1843, at just 24 years old, Lugenbeel received a dual appointment that would position him to witness the Liberia constitutional convention four years later:

- Colonial Physician for Liberia (American Colonization Society)

- U.S. Government Agent for Recaptured Africans

The second role deserves explanation. After the United States banned the international slave trade in 1808, the U.S. Navy’s Africa Squadron intercepted illegal slave ships. The enslaved people rescued from these ships—called “recaptured Africans”—needed resettlement. Many were sent to Liberia, and Lugenbeel managed this complex humanitarian operation.

July 26, 1847: Witnessing History

Liberia’s Constitutional Convention

By 1847, Liberia was transitioning from an American Colonization Society colony to an independent nation. The Liberia constitutional convention brought together elected delegates to debate and craft the governing document for what would become Africa’s first republic.

On July 26, 1847, the delegates formally adopted Liberia’s Constitution, creating Africa’s first independent republic. Dr. Lugenbeel documented the debates, arguments, and compromises that produced this historic document. While the constitutional text survives, his journal provides the only record of how these provisions were debated and decided.

Dr. Lugenbeel, as colonial physician and government agent, attended the proceedings and kept meticulous notes. His journal captured:

- The structure of government debates

- Questions of citizenship and voting rights

- Discussions about relations with indigenous populations

- Compromises between different factions

- The human deliberation behind the historic document

Why the Liberia Constitutional Convention Journal Matters

Here’s what makes Lugenbeel’s journal historically irreplaceable: it’s the only documentation that survived.

Lugenbeel’s observations survive through his official correspondence to the American Colonization Society, written in October 1847—just months after the July constitutional convention while events remained fresh in his memory. These excerpts from his journal were preserved in a letter to ACS Secretary William McLain and represent the only known eyewitness American account of this historic gathering. The fact that these observations were part of formal reporting to ACS headquarters, rather than casual correspondence, suggests Lugenbeel carefully selected and documented what he considered most significant about the constitutional process.

We have Liberia’s final constitution. We know what it said. But without Lugenbeel’s journal, we wouldn’t know why certain provisions were included, how delegates argued different positions, or what compromises were necessary to reach consensus.

For scholars studying constitutional formation, democratic deliberation in colonial contexts, or how formerly enslaved people structured self-governance, Lugenbeel’s journal is essential.

And that journal exists only because one Alexandria physician took detailed notes at a constitutional convention 178 years ago.

“Sketches of Liberia” (1850)

Publishing His Observations

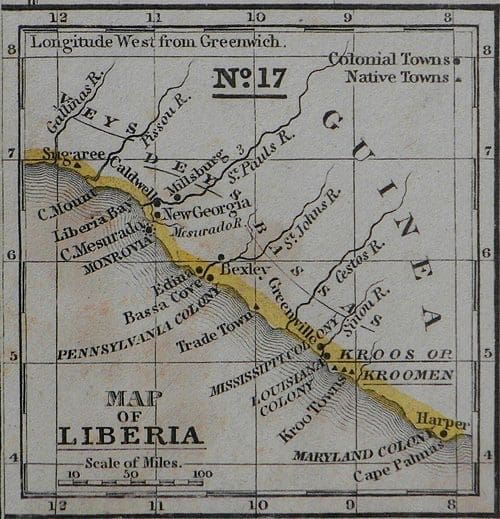

In 1850, he published Sketches of Liberia: Comprising a Brief Account of the Geography, Climate, Productions, and Diseases of the Republic of Liberia—a comprehensive work that remains a valuable primary source for scholars studying early Liberian society.

The 1850 publication offered American readers their first detailed look at Liberian society, including:

- Medical observations on tropical diseases and climate health challenges

- Geographic descriptions of the coastal settlements

- Ethnographic documentation of indigenous customs and cultures

- Agricultural potential and economic prospects

- Social structure of the young republic

Lugenbeel’s complete 1850 work is digitized and freely available through the Internet Archive, allowing modern readers to explore his firsthand observations of the young republic he helped document at the Liberia constitutional convention.

Sketches of Liberia remains a valuable primary source today. Historians, anthropologists, and Liberian studies scholars still cite Lugenbeel’s firsthand observations when researching early Liberian society.

The American Colonization Society: A Complex Legacy

Understanding the ACS

To understand Lugenbeel’s work, you need to understand the American Colonization Society (founded 1816-1817). The organization promoted African American emigration to West Africa, establishing what would become Liberia.

But the ACS’s legacy is complicated:

Supporters included:

- Some abolitionists who saw colonization as gradual emancipation

- White Americans who wanted to remove free Blacks

- Free African Americans seeking self-determination in Africa

- Religious missionaries focused on spreading Christianity

Opponents included:

- Immediate abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison (who wanted slavery ended in America, not exported)

- Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders (who viewed it as deportation)

- Many free African Americans (who considered America their home)

Haiti vs. Liberia: The Untold Story

Here’s a fact most people don’t know: more African Americans emigrated to Haiti (over 15,000) than to Liberia during this period.

After Haiti’s independence in 1804, the Haitian government actively recruited African American emigrants. Many found Haiti more appealing because:

- It was an established independent Black republic

- Closer geographically to the United States

- French/Creole culture more familiar than West African

- Didn’t carry the same ACS controversial associations

Yet Liberia became the more lasting symbol of colonization—partly because the ACS actively promoted it, and partly because Haiti’s political instability made many emigrants return to the United States.

A Life Cut Short

Return to Alexandria and Death

After his service in Liberia, Dr. Lugenbeel returned to Alexandria and continued working with the American Colonization Society. His expertise earned him election as Recording Secretary at the Society’s 1852 annual meeting—a role that recognized his meticulous documentation skills first demonstrated in his Liberia constitutional convention journal.

Throughout the Annual Reports of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States, Lugenbeel’s observations and recommendations appear frequently, informing the Society’s policies and public communications about Liberian colonization efforts.

On September 22, 1857, Dr. James Washington Lugenbeel died at just 38 years old.

His obituary in the Alexandria Gazette emphasized his “deep Christian faith” and “invaluable contributions to the Society’s humanitarian mission.” Colleagues mourned the loss of one of the few Americans with firsthand knowledge of Liberian medical and social conditions.

The Open Book Symbol

Visit Lugenbeel’s grave in Trinity Methodist Cemetery today, and you’ll see the carved image of an open book on his gravestone. This was a traditional Victorian mourning symbol representing a life ended prematurely—pages left unwritten, chapters never completed.

The gravestone inscription reads:

| JAMES W. LUGENBEEL died Sept 22nd 1857 Aged 38 Years But God will redeem my soul from the power of the grave: for he shall receive me. Psalm XLIX. XV. |

The symbolism is particularly poignant for Dr. Lugenbeel:

- He was a published author (Sketches of Liberia)

- He was a chronicler (constitutional convention journal)

- He died at 38 with potentially decades of documentation ahead

- His “book” of life closed too early

One wonders what other observations, journals, and publications he might have produced had he lived to 60 or 70. What additional documentation of Liberian society might exist today?

The open book on his gravestone represents not just his death, but the historical record that died with him.

The Family He Left Behind

Dr. Lugenbeel’s death at age 38 left his wife Martha and ten-year-old daughter Emily to navigate life without husband and father. Martha never remarried, living thirty years as a widow.

Mother and daughter continued living with Susan and Thomas Davy at 25 South Royal Street in Alexandria. When Susan died in 1872, she was buried in Trinity Methodist Cemetery where Dr. Lugenbeel rested. Emily married Robert Rezin Redman McCaine in 1866; after that marriage ended, she married Finley Anderson in New York City in 1875. Martha eventually followed her daughter north.

Martha Alice Lugenbeel died in New York City on June 17, 1887, and was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx—choosing to rest near her daughter rather than beside her husband in Alexandria. Thirty years later, Emily died in Manhattan at age seventy and was buried at Woodlawn beside her mother.

The Alexandria Gazette remembered Martha as a “former Alexandria lady” whose husband “practiced in Liberia for about six years under the auspices of the American Colonization Society.” Emily had no children. Dr. Lugenbeel’s direct line ended with his daughter in 1917. His legacy survives not through descendants, but through the journal and published work that preserved Liberia’s founding.

Why Lugenbeel Matters Today

For Liberian Studies

Dr. Lugenbeel’s journal and published work remain essential sources for anyone studying:

- Liberian constitutional history

- Early republican government in Africa

- Medical conditions in 19th-century West African settlements

- American Colonization Society operations

- Recaptured African resettlement programs

For Understanding American History

Lugenbeel’s story connects to broader American historical themes:

- The complexity of pre-Civil War racial politics

- Debates about colonization vs. abolition

- Federal government’s role in African colonization

- How American policy shaped African independence movements

- The international reach of American slavery’s legacy

For Alexandria

Lugenbeel represents Alexandria’s often-overlooked international connections. While most Alexandria tours focus on George Washington, Robert E. Lee, and Civil War history, Lugenbeel’s story shows:

- Alexandrians participating in African independence

- Local connections to international humanitarian efforts

- The city’s role in complex racial and political debates

- Global significance of people buried in local cemeteries

Finding Lugenbeel’s Grave

Location

Dr. James W. Lugenbeel is buried in Trinity Methodist Cemetery, part of Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Address: Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, 1475-1501 Wilkes Street, Alexandria, VA 22314

What to Look For

- Weathered gravestone (1857)

- Carved open book symbol

- Name: James W. Lugenbeel

- Dates: 1819-1857

- Located in Trinity Methodist Cemetery section

Visiting the Complex

The Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex contains 13 historic cemeteries spanning 1796-1933. It’s America’s largest concentration of historic cemeteries in one square mile, with over 35,000 documented burials.

While you’re there to see Lugenbeel’s grave, you’ll discover hundreds of other significant historical figures—Revolutionary War veterans, Civil War soldiers, founding families, and everyday Alexandrians who shaped American history.

Book a guided tour to learn stories you won’t find anywhere else.

The Bigger Picture: Hidden History in Plain Sight

What Else is Buried Here?

Dr. Lugenbeel is just one of hundreds of significant figures buried in Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex whose stories remain largely unknown:

- George Washington’s pallbearers

- The highest-ranking Confederate general (who outranked Lee)

- A Cold War spy

- The man whose homes bookended the Civil War

- Buffalo Soldiers and USCT heroes

- Chroniclers, physicians, and witnesses to history

Most visitors to Alexandria never venture west of King Street. They tour historic buildings, hear about Washington and Lee, and leave without knowing that some of America’s most significant historical figures—and the stories they documented—are buried just minutes away.

Why These Stories Matter

Lugenbeel’s grave represents a fundamental truth about historical preservation:

The most important stories aren’t always the most famous ones.

You won’t find Dr. Lugenbeel in most history textbooks. He’s not on Alexandria’s tourist corridor. There’s no historical marker, no museum exhibit, no prominent recognition.

But without his journal, we wouldn’t understand how Liberia’s founders created Africa’s first independent republic.

That’s the kind of hidden history waiting to be discovered in Alexandria’s cemeteries—if you know where to look and what questions to ask.

Explore More

Related Stories:

- Victorian Gravestone Symbols: Reading the Language of the Dead

- Trinity Methodist Cemetery: Notable Burials

Plan Your Visit:

- Book a Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex Tour

- Download Self-Guided Brochure (PDF)

- View Interactive Cemetery Map

- Alexandria History Timeline

Found this interesting? Help others discover Alexandria’s hidden history by sharing this story.

Primary Sources & Further Reading

Historical Documents:

Liberia’s 1847 Constitution – The constitutional document adopted at the convention Dr. Lugenbeel documented (via Internet Archive)

Lugenbeel, James W. Sketches of Liberia: Comprising a Brief Account of the Geography, Climate, Productions, and Diseases of the Republic of Liberia. Washington, D.C., 1850. Complete digitized text available via Internet Archive.

Scholarly Articles:

Mills, B. (2014). “The United States of Africa”: Liberian independence and the contested meaning of a Black Republic. Journal of the Early Republic, 34(1), 79-107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486932

This article provides a critical analysis of how Liberian independence was received in the United States. It documents the provenance of Lugenbeel’s constitutional convention journal excerpts, which survived through his October 9, 1847, letter to ACS Secretary William McLain (ACSP, Series 1, Reel 173).

Archival Collections:

Lugenbeel, James Washington. James Washington Lugenbeel Manuscripts. Historical Manuscripts Collection, Drew University. Accessed via JSTOR Community Collections. Contains personal papers, correspondence, and medical observations from Liberia.

American Colonization Society. The Annual Reports of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States, Volumes 1-10 (1818-1827). HathiTrust Digital Library. Dr. Lugenbeel is cited frequently throughout later annual reports and was elected Recording Secretary at the Society’s 1852 annual meeting.

American Colonization Society. The Annual Reports of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969. [Reprint edition containing complete run of reports 1818-1910]

Cemetery Documentation:

Pippenger, Wesley E. Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, Virginia: Volume 1. Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications; Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1992. [Dr. Lugenbeel’s gravestone inscription, Trinity Methodist Cemetery]

Gravestone Stories documentation and photographic archives of the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex, Alexandria, Virginia (13 cemeteries, 1796-1933, 35,000+ documented burials)

Contemporary Sources:

Dr. J. W. Lugenbeel [Obituary]. (1857, September 24). Alexandria Gazette, p. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/article/alexandria-gazette-g-w-lugenbeel-obitu/187265203/

American Colonization Society correspondence and meeting minutes, 1843-1857

Research Notes:

The original constitutional convention journal referenced in Lugenbeel’s published work and ACS annual reports has not been located in modern archival collections. Its whereabouts remain unknown, making it one of American historical documentation’s most significant missing sources.

Dr. Lugenbeel is buried at Trinity Methodist Cemetery, part of Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex (1475-1501 Wilkes Street, Alexandria, VA 22314). His gravestone features a carved open book symbol—a Victorian mourning motif representing a life ended prematurely.

About This Research:

This article draws on primary source documentation including Lugenbeel’s published work, archival manuscripts, American Colonization Society records, and cemetery documentation. Gravestone Stories maintains comprehensive biographical records for over 35,000 burials across Alexandria’s 13 historic cemeteries in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex.

Book a tour | View Interactive Cemetery Maps | Alexandria History Timeline