Origins of the Quaker Cemetery

The Quaker Burial Ground in Alexandria, VA illustrates the city’s layered history and the lasting influence of the Quaker community, tracing a remarkable transformation from sacred burial space to modern civic landmark while preserving the memory of those who shaped Alexandria’s early development.

Established in the late eighteenth century, the burial ground reflects both the growth of Alexandria and the evolving role of the Quaker community within it.

Transition to a New Resting Place

By 1809, following town edicts that prohibited new burials after May 1, 1809, due to concerns about yellow fever, the Quaker community ceased burials at the Queen Street location. You can learn more [here]. They began using the Friends in the District of Columbia cemetery at the start of 19th Street beyond Columbia Road.

The Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library

Today, the Quaker burial ground has become the Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library at 717 Queen Street. Respecting Quaker traditions, the graves from before the library’s construction remain beneath the library’s parking lot and grounds. Some gravestones were moved to the Quaker burial ground near the Quaker Meeting House, south of Alexandria, near the Woodlawn Plantation.

Of the 159 individuals buried in the Alexandria Quaker burial ground, 66 were relocated to different areas within the same site to accommodate the library’s construction. The remaining 93 continue to rest undisturbed in their original locations. Unfortunately, records for only 78 of these burials have been preserved.

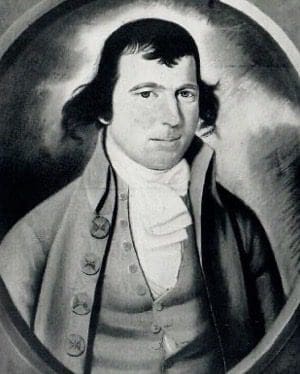

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick: A Life of Note

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick was a prominent Alexandrian physician, civic leader, and Freemason whose life intersected with many of the formative moments of the early American republic. Born on March 15, 1762, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, he was raised in a distinguished Revolutionary family. His father, Archibald Dick, served as a major in the Continental Army and later as Deputy Quartermaster General before his death in 1782.

As a youth, Elisha Cullen Dick received a classical education in Pennsylvania and completed his studies under the tutelage of Episcopal clergymen, including the Rev. Samuel Armor. In 1780, he commenced the study of medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush and later completed his formal medical education under Dr. William Shippen, receiving the degree of Bachelor of Medicine in 1782.

After briefly considering establishing his practice in Charleston, South Carolina, Dick settled permanently in Alexandria in 1783 at the invitation of influential residents, following the death of one of the town’s leading physicians. He quickly became one of Alexandria’s most respected medical practitioners.

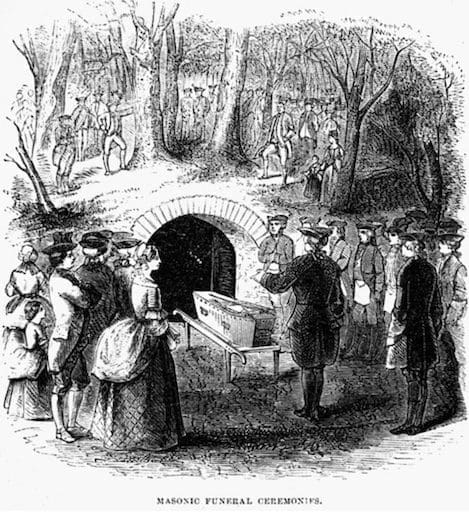

Masonic Leadership and National Ceremonies

Dr. Dick succeeded George Washington as Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 and presided over several landmark Masonic ceremonies, including the 1791 placement of a boundary stone at Jones Point marking the beginning of the District of Columbia and the 1793 laying of the cornerstone of the United States Capitol. He was also among the physicians present during George Washington’s final illness in December 1799. (For more on this period, see the blogs: [Dr. James Craik: George Washington’s Lifelong Friend and Physician | A Tale of Commitment and Friendship] and [Caroline Branham: the Enslaved Chambermaid Who Witnessed George Washington’s Final Moments].)

Mourning the Father of the Nation

Dr. Dick’s role did not end when George Washington died. As Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22, he conducted the Masonic “Lodge of Sorrow” for Washington and helped lead the town’s formal expressions of grief. On December 18, 1799, at Mount Vernon, the funeral service began at three o’clock in the afternoon and continued until dusk. At the graveside, it was Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick who read the burial service—described by contemporaries as being delivered with great dignity and solemnity.

In the weeks that followed, Dr. Dick emerged as one of Alexandria’s principal voices of public remembrance. On February 22, 1800—Washington’s birthday—citizens processed from the town’s Market Square to the Presbyterian Meeting House. There, Dr. Dick delivered a major public address that became one of the earliest civic memorials to Washington anywhere in the nation. His words resonated deeply with Alexandrians: “America has lost its first of patriots and best of men… the statesman’s polar star, the hero’s destiny, the companion of maturity, and the goal of youth.”

This memorial observance—initiated during Dr. Dick’s lifetime—became an annual tradition in Alexandria that continues to this day.

Civic Leadership and Public Health

In Alexandria, Dr. Dick held numerous public offices, including health officer, justice of the peace, coroner, and mayor. As Superintendent of the Yellow Fever Quarantine, he played a critical role in safeguarding the town during repeated epidemics in the early nineteenth century.

His authority extended beyond ceremonial duties to life-and-death decision-making. In correspondence to Governor James Monroe, Dr. Dick described ordering the quarantine of a vessel arriving from New Orleans with yellow fever aboard—two crew members already dead: “Exercising a discretionary power given by the quarantine laws to the Superintendant, I have caused this ship to commence her quarantine near this place between Rozins Bluff and Jones Point.” His decisions carried profound consequences for Alexandria’s port city economy and public health.

Military Service

Dr. Dick also commanded a cavalry company raised in Alexandria during the suppression of the Whiskey Insurrection in 1794, returning to his native Pennsylvania not as a physician but as a cavalry officer under the command of “Light Horse Harry” Lee.

During the War of 1812, Dr. Dick’s civic leadership was tested again. On August 25, 1814, the day after British forces burned Washington, Dr. Dick joined Presbyterian minister James Muir and Episcopal rector William Holland Wilmer in a desperate mission through a violent storm to meet Rear Admiral George Cockburn in Georgetown, seeking terms to spare Alexandria. Though Cockburn offered informal assurances, the town was later forced to formally surrender to Captain James Alexander Gordon’s Potomac Squadron, leading to occupation and large-scale plundering.

Financial Challenges and Resilience

Dr. Dick had invested heavily in commercial ventures beyond his medical practice, buying and selling land, houses, ships, and cargo. In 1797, he sold the brig Julia with its full cargo of flour and corn for ten thousand dollars. Despite such substantial transactions, poor investments led him to declare bankruptcy in 1801.

Nevertheless, he remained a respected figure in Alexandria. Two years later, when yellow fever struck in 1803, the town still turned to him for leadership. In 1804—just three years after bankruptcy—Alexandria elected him mayor. Financial failure had not erased moral authority.

Personal Life and Character

In 1885, Dr. Dick’s great-grandson described him as a tall man of commanding presence—five feet ten inches—with a fine voice, an ear for music, and a deep love of learning. He sang, played instruments, and moved comfortably in social settings, remembered for warmth, intellect, and humanity.

A Celebrated Dinner Invitation in Rhyme by Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick

This unique poetic invitation was penned for Dr. Dick’s close friend, Philip Wanton, who resided in a quaint frame house once located at 216 Prince Street. The house long ago disappeared.

If you can eat a good fat duck, Come up with us and take pot luck, Of whitebacks we have got a pair So plump, so round, so fat, & fair A London Alderman would fight Through pies and tarts to get one bite.

Moreover, we have beef or pork That you may use your knife and fork. Come up precisely at two o’clock The door shall open at your knock. The day tho’ wet, the streets tho’ muddy To keep out the cold we’ll have some toddy.

And if, perchance, you should get sick, You’ll have at hand Yours E. C. Dick

Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick’s playful and inviting rhyme showcases not only his medical prowess but his flair for poetic expression and social warmth. This piece serves as a delightful reminder of the multifaceted talents that historical figures often possess.

Religious Transformation and Moral Conviction

Although sometimes described in later secondary sources as having been Presbyterian, archival and family correspondence clarifies that Dr. Dick was not a Presbyterian. He was raised and educated within an Episcopal milieu and, later in life, became a committed member of the Society of Friends. Contemporary Quaker authorities familiar with Friends’ disciplinary records affirmed that he died and was buried as a member of the Society in the Friends Burying Ground on Queen Street.

In the latter part of his life, Dr. Dick’s beliefs increasingly reflected Quaker principles, including an emphasis on pacifism, moral reform, and personal responsibility. He demonstrated these convictions through concrete actions. In 1811, he manumitted Nancy, an enslaved woman of about forty years, granting her freedom around the time of his conversion to the Society of Friends, who opposed slavery on moral grounds. He also renounced dueling by throwing his pistols into the Potomac River; they were later recovered and are now preserved at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial as evidence of his transformed life.

Family and Legacy

Dr. Dick married Hannah Harmon of Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1783. The couple had three children, including Julia Dick, who married Gideon Pearce. Their grandson, James Alfred Pearce, was raised in Alexandria and later served as a U.S. Senator from Maryland for nineteen years (1843-1862), becoming known for his erudition and his role in crafting the Pearce Plan as part of the Compromise of 1850.

Remembered by family and contemporaries as a man of intellect, musical talent, and moral seriousness, Dr. Dick was described in later family correspondence as a zealous member of the Society of Friends in the latter part of his life.

Death and Burial

On September 22, 1825, Elisha Cullen Dick died at his Cottage Farm residence in what is now the Lincolnia section of Fairfax County. His remains were transported through Alexandria on a funeral wagon and interred in an unmarked grave in the Friends Burying Ground on Queen Street—now the site of the Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library. Thus, one of Alexandria’s most distinguished early citizens rests beneath a place where modern Alexandrians gather to read and learn, largely unaware of the remarkable man buried beneath their feet.

Conclusion

The Quaker burial grounds in Alexandria reflect the city’s layered past and the enduring influence of the Quaker community, illustrating a transformation from sacred burial space to modern civic landmark.

Sources of Information

Primary Archival Sources

Alexandria Library, Special Collections Division (Kate Waller Barrett Library), Alexandria, Virginia.

- Pearce, James Alfred. (1885, August 20). Letter to Dr. A. M. Toner, Washington, D.C. Genealogical record and biographical details concerning Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick. Contains family history, physical description, education, medical training, civic service, religious affiliation, and confirmation of burial in the Friends Burying Ground on Queen Street. William Buckner McGroarty Papers, Alexandria Library.

- Janney, Mahlon Hopkins. (1941, April 21). Letter discussing Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick and Quaker meeting records. Addresses Quaker disciplinary practices, terminology, and Dick’s status as a member of the Society of Friends at the time of his death. William Buckner McGroarty Papers, Alexandria Library.

- McGroarty, W. B. (1941, April 22). Letter correcting denominational attribution regarding Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick and discussing his burial. Includes contextual explanation of earlier clerical error. William Buckner McGroarty Papers, Alexandria Library.

- Dick, Elisha Cullen. (1795, September 4). Letter to His Excellency Robert Brooke, Governor of Virginia. Correspondence regarding quarantine responsibilities and compensation. William Buckner McGroarty Papers, Alexandria Library.

Published and Visual Sources

- Alexandria Association. (1956). Our Town at Gadsby’s Tavern, Plate VII.

- Cox, Allyn. Washington Laying the Cornerstone of the United States Capitol. United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.

- Dr. Elisha Dick Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. (1983). Doctor Elisha Cullen Dick, 1762-1825. Brochure prepared for the 45th Anniversary celebration. Contains biographical details, dinner invitation poem, and information about dueling pistols.

- Lord, Walter. (1972). The Dawn’s Early Light. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Miller, T. Michael. (1986). Visitors from the Past: A Bicentennial Reflection on Life at the Lee-Fendall House 1785-1985. Alexandria, VA: Virginia Trust for Historic Preservation. (Out of print; eight known copies extant, including one at Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library, Alexandria, Virginia)

- Moore, Gay Montague. (1949). Seaport in Virginia: George Washington’s Alexandria. Richmond, VA: Garrett & Massie.

- Stearns, Junius Brutus (after). (1853). Life of George Washington: The Christian. Lithograph by Claude Regnier. Library of Congress.

Related Gravestone Stories Essays

- Dr. James Craik: George Washington’s Lifelong Friend and Physician

- Caroline Branham: The Enslaved Chambermaid Who Witnessed George Washington’s Final Moments

Update Note

This article was originally published in September 2023. It was substantially updated in February 2026 to include newly researched archival materials and primary source documentation, including Dr. Dick’s role in the War of 1812 peace delegation, his manumission of Nancy in 1811, details of his commercial ventures and bankruptcy, correspondence with Governor James Monroe regarding quarantine authority, expanded information about his grandson Senator James Alfred Pearce, and clarification of his religious affiliations based on archival correspondence. Sources have been expanded to reflect this additional research.