The Overlooked Battle of the Potomac and its Historical Significance

In the early stages of the War of 1812, American forces took decisive action in April 1813. They successfully captured York (present-day Toronto, Canada) and set it ablaze in a controversial move. This aggressive act was not without consequences. Following Napoleon’s defeat in Europe, the British redirected their resources and troops towards North America in retaliation. This heightened tension culminated on August 24, 1814, when the British forces captured Washington D.C., setting significant parts of the city, including the White House, on fire.

Yet, amidst these pivotal historical moments, an often overshadowed battle played out on the Potomac River from September 1 to 5, 1814. This battle, coming hot on the heels of the sacking of Washington, would set the stage for a critical encounter. This engagement on the Potomac directly precipitated the British assault on Baltimore later in September. This siege defended American territory and provided the backdrop for the creation of the United States National Anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s Ambitious Strategy: The Plan to Subdue Key American Cities

With reinforcements en route to Bermuda, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, the commander responsible for the British Navy’s operations in North America, had a grand vision in mind. He aspired to seize several pivotal American cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, and Richmond. His intention wasn’t merely conquest; it was to execute these campaigns swiftly and leave a trail of devastation in his wake. The overarching aim was to leave the American spirit so broken that they’d be compelled to seek peace.

Cochrane’s audacious strategy was not left to speculation. He meticulously laid out this vision in a letter addressed to Robert Saunders on July 17, 1814. Beyond mere military dominance, his correspondence reveals a keen desire to wield psychological warfare, forcing the Americans to capitulate.

Dated September 10, 1814, and later published in the Alexandria Gazette on September 15, 1814, British Vice-Admiral Alex Cochrane addresses The Hon. James Monroe, Secretary of State, from aboard his flagship, the H.M.S Tonnant. In this correspondence, Cochrane criticizes the “wanton destruction” by the American army in Upper Canada and advocates for retaliatory measures against the U.S. inhabitants.

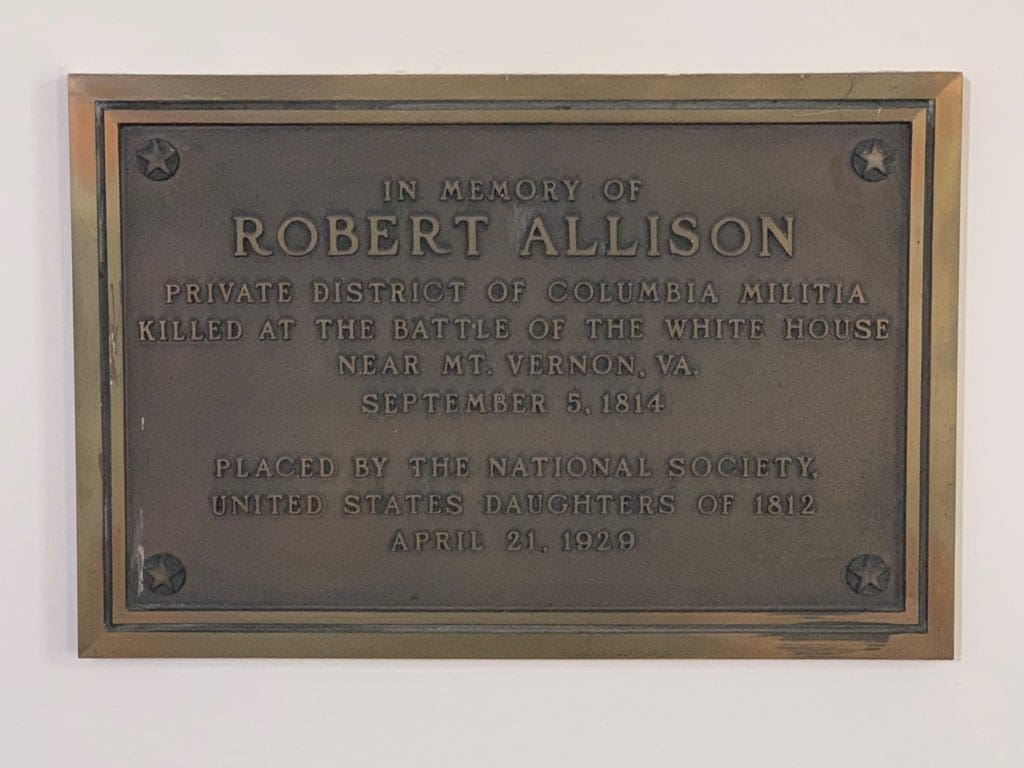

The Legacy of Robert Allison Jr. and the Battle of the White House

The tale unfurls further in the Presbyterian Cemetery in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex in Alexandria, Virginia. Here, one can find a sandstone gravestone etched with simple yet poignant words, marking the final resting place of Robert Allison Jr.

| In Memory of ROBERT ALLISON, Jr. who fell in battle on the 5th Septr. 1814 at the white house in gallantly defending his country aged 27 years Our lives belong to God, & our country He was a dutiful son an affectionate Brother conciliating in manners beloved by all erected by his kinsman JAMES M. STEWART |

Robert Allison Jr.’s lineage is intertwined with Alexandria’s history. He was the grandson of William Ramsay, a foundational figure who played a role in establishing Alexandria and served as its first mayor. Allison’s ties to the Ramsay family continued through Allison’s mother, Ann Ramsay, William Ramsay’s descendant. His father’s side wasn’t any less illustrious. Sea Captain Robert Allison Sr. made a name as a merchant of Alexandria and served as a Justice of Fairfax County during the American Revolution.

Faith played a central role in Allison’s life, evidenced by his association with Alexandria’s Presbyterian Meeting House. It’s worth noting another congregant of this spiritual abode: Samuel Bowen. He, too, paid the ultimate sacrifice during the same era as Allison. Sadly, while he found eternal peace in the same Presbyterian Cemetery, the exact location of his grave remains a mystery.

Robert Allison Jr.’s demise coincided with the climax of a five-day engagement known as the “Battle of the White House (Landing).” This skirmish pitted the American militia against seven British ships sailing the Potomac River. These British ships would later play a role in the assault on Baltimore following the capture and burning of Washington on August 24, 1814.

Captain James Alexander Gordon and the Potomac Squadron’s Tactical Role in 1814

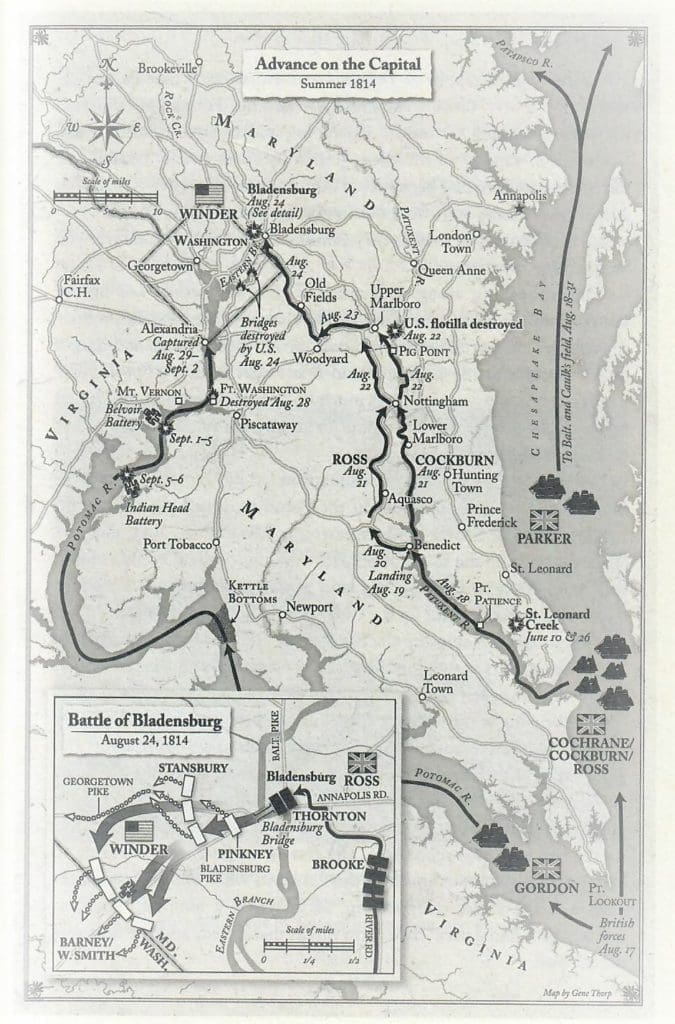

On August 17, 1814, the dominant British fleet, brimming with 4000 soldiers, began its strategic journey up the Patuxent River, setting its course for Benedict, Maryland. The mission was clear: disembark the troops for their subsequent march towards Washington. A calculated ruse was set in motion to divert American attention from these primary landings effectively. The British dispatched the Potomac Squadron, a smaller fleet, to journey up the Potomac River.

At the helm of this squadron stood Captain James Alexander Gordon, a stalwart one-legged Scot with an impressive service record. A veteran of the British Navy, Gordon had the honor of serving under the legendary Lord Nelson and had battled in the pivotal wars against Napoleon. The squadron he commanded was formidable, comprising warships such as the Seahorse and Euryalus. It also included explosive vessels: Meteor, Aetna, and Devastation; the rocket-equipped Erebus; and the essential message carrier, Anna Maria. Altogether, Gordon’s fleet boasted a daunting arsenal of 173 guns.

Renowned British Captain from the Napoleonic Wars, Captain James Alexander Gordon is depicted here as the commander of the Potomac River. Notably, while leading the 38-gun frigate HMS Active against three superior French frigates near Palagruža, Croatia, in the Adriatic Sea in November 1811, a cannonball grievously injured his left knee, necessitating the amputation of his leg.

Artwork by Andrew Morton.

© National Maritime Museum Collections.

The objective of the Potomac Squadron was to navigate upriver and lay siege to Fort Warburton. After the War of 1812, the fort underwent reconstruction and was rechristened as Fort Washington. Today, it is a historical park managed by the National Park Service. The squadron’s responsibilities weren’t confined to offensive action; their defensive posture was to shield against potential incursions via the Potomac River. This move was designed to envelop Washington from the water as British infantry pressed on from the eastern front. Moreover, if the Patuxent River route faced obstructions, the squadron’s vessels stood ready to transport British soldiers, ensuring troop movements.

This illustration delineates the British forces’ path toward Washington in August 1814, highlighting the Potomac Squadron’s strategic river route. Key landmarks include the Kettle Bottoms and the significant batteries at Indian Head, Belvoir Neck, and Fort Washington (formerly Warburton). It was extracted from page 65 of Steve Vogel’s “Through the Perilous Fight.”

The British Conquest of Washington, August 1814

On August 24, 1814, the British forces triumphed over an American army comprised largely of novice troops, complemented by a group of U.S. Marines and U.S. Regulars. This confrontation, lasting two hours, paved the way for the British to march into Washington. Over the following day and night, they engaged in a campaign of destruction, setting ablaze and ravaging U.S. government edifices and properties.

This artwork, illustrated by Colonel Charles Waterhouse, captures Captain Samuel Miller’s Marines in their valiant yet final attempt to repel the British from the U.S. capital. The American defeat on August 24, 1814, culminated in the devastating burning of Washington, an act of retribution for the Americans’ previous torching of York, Upper Canada, the preceding year. — Public Domain.

This restored watercolor and ink rendering from 1814 captures the haunting visage of the United States Capitol following the devastating inferno in Washington, D.C., during the War of 1812. — Library of Congress.

Challenges of Gordon’s Potomac Squadron During the Washington Assault

While British infantry advanced on Washington, Captain Gordon’s Potomac Squadron faced significant navigational challenges. The treacherous waters of the Kettle Bottoms demanded the expertise of additional pilots. Compounding their problems, opposing winds hampered their progress, leaving them approximately 50 miles downstream when Washington fell to the British. That night, a glowing sky ominously illuminated the horizon, signaling the crew to the massive blaze burning to the north.

The Storm that Saved Washington: Nature’s Wrath During the War of 1812

On the afternoon of August 25th, Washington experienced the fury of a powerful front of winds and thunderstorms, believed by some to be a derecho, that swept in from the west. The wind uprooted roofs and wreaked havoc on structures. Amidst the chaos, a tornado spiraled through the heart of Washington, touching down on Constitution Avenue. This tornado lifted two cannons, only to deposit them yards away, resulting in casualties among British soldiers and American civilians. While parts of Washington suffered damage, the storm’s rains, pouring down for hours, extinguished the fires set ablaze by the British the previous day. The storm, though devastating, played a pivotal role in preserving Washington, effectively saving the city from further destruction.

The Potomac Squadron, under Captain Gordon’s command, didn’t fare much better. Ships in the squadron bore the brunt of the storm, with masts snapping, sails rending, and supplies thrown overboard. The waters jostled the ships akin to playthings in turbulent waters. One bomb vessel met an unfortunate fate, being thrust onto a sandbank and subsequently damaged. Amidst this turmoil, Commodore Gordon contemplated retreat. However, the resilience and determination of his captains and crew, convinced of their ability to address the damages, persuaded him to persist in their journey upriver.

Dr. William Beanes’ Arrest: A Pivot in History

After the storm subsided, the British army in Washington decided to leave and return to their ships on the Patuxent River. As the British troops retreated towards their vessels anchored in Benedict, Maryland, some stragglers engaged in plundering local homes. During one such incident, Dr. William Beanes, a prominent civilian hosting a gathering, confronted a British soldier attempting to loot his residence. With the assistance of his guests, Beanes apprehended the intruder and several of his comrades. Fearing retribution from the larger British contingent, they transported their captives to a jail nine miles away. Upon discovering this act, the British retaliated by arresting Dr. Beanes and confining him within the prison quarters of their flagship, the H.M.S Tonnant. Beanes’ arrest would set into motion a series of events with profound implications in history.

The Fall of Fort Warburton

The Potomac Squadron’s Journey

Meanwhile, the Potomac Squadron, which had recovered from the derecho, continued upriver. On August 27th, at 5:00 p.m., after a ten-day journey marred by unfavorable winds and frequent groundings, the Potomac Squadron reached Mount Vernon on their way up the Potomac River. They bypassed the estate without disturbance, recognizing its namesake, Vice Admiral Edward Vernon—a British naval hero who captured Porto Bello and besieged Cartagena. Lawrence Washington, a former subordinate of Vernon, had renamed his estate, originally known as Little Hunting Creek Plantation, to Mount Vernon after returning from serving under Vernon in the West Indies. His half-brother, George, eventually inherited Mount Vernon in 1761 after the death of Lawrence’s wife, Anne.

Struggles on the Potomac

The Potomac Squadron’s journey was rife with challenges, from negotiating the Kettle Bottoms to the lack of wind. Each ship ran aground over 20 times, compelling the crew to rely on the technique of warping, where they used a line attached to an anchor or stationary object to move against the wind. This method was employed for five consecutive days, covering over 50 miles. The exhaustion was palpable, but their most significant test awaited.

Fort Warburton: An Ill-Prepared Defense

Three miles beyond Mount Vernon stood Fort Warburton on the Maryland side. It seemed formidable, equipped with a water battery, a rear battery, a two-story brick building, and an impressive arsenal of 26 guns. However, its defenses were compromised by a mere 57 men available to man the station.

Amidst the anticipation of the Potomac Squadron’s arrival, a rumor reached Captain Samuel Dyson, the fort’s commander. Local sources falsely claimed that the British army, having vacated Washington on the 25th, intended to seize the fort from the east.

Captain Dyson’s Fateful Decision

Faced with the dual threats of a rumored land invasion and the approaching Potomac Squadron, Dyson convened his officers. He disclosed that he’d received orders to destroy the fort should its capture become imminent—a scenario he deemed was unfolding. Ordering the fort’s guns to be disabled and a gunpowder trail to the storage ignited, Dyson’s actions deeply unsettled his troops. They were bewildered at their leader choosing destruction without a fight. This act would later result in Dyson’s military trial, ultimately leading to his discharge for desertion and the unauthorized destruction of government property.

The Cataclysmic End

As Dyson’s commands went into action, Gordon’s squadron commenced their assault, interpreting the fort’s evacuation as a potential ruse. Then, at 6:30 p.m., a massive explosion rocked the area. While Gordon initially suspected a fortuitous cannon strike, the reality was the ignition of the fort’s stored powder. This explosion obliterated Fort Warburton in its entirety.

The Alexandria Negotiation

The Approach from Alexandria

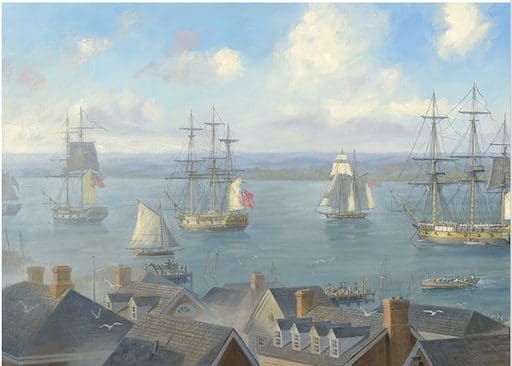

On the morning of August 28th, while the Potomac Squadron was finishing its operations at the recently devastated Fort Warburton, Commodore Gordon noticed a boat carrying a truce flag descending the river towards his fleet. This vessel had set out from Alexandria, a town just six miles upstream.

By evening, the squadron had reached the vicinity of Alexandria. The following morning, it positioned itself in a battle formation a few hundred yards from the piers and homes, a position that could have quickly laid waste to the town.

Alexandria: A Prosperous Port at Risk

Renowned as a bustling port, Alexandria facilitated trade between Europe and the Caribbean, becoming a hub of wealth and commerce. Despite its prosperity, the town found itself defenseless against the looming threat of the Potomac Squadron. Recognizing their vulnerability, Alexandria’s leaders opted for diplomacy over confrontation.

Emissaries of Peace

Mayor Charles Simms and Edmund Jennings Lee, Sr., a distinguished lawyer and politician of Alexandria, took the lead in this peace endeavor. Lee, a member of the illustrious Lee family of Virginia, resided at the historic Lee-Fendall House, still standing on Oronoco Street in Alexandria. Jonathan Swift and the mayor himself accompanied them on this crucial mission.

Gordon’s Demands

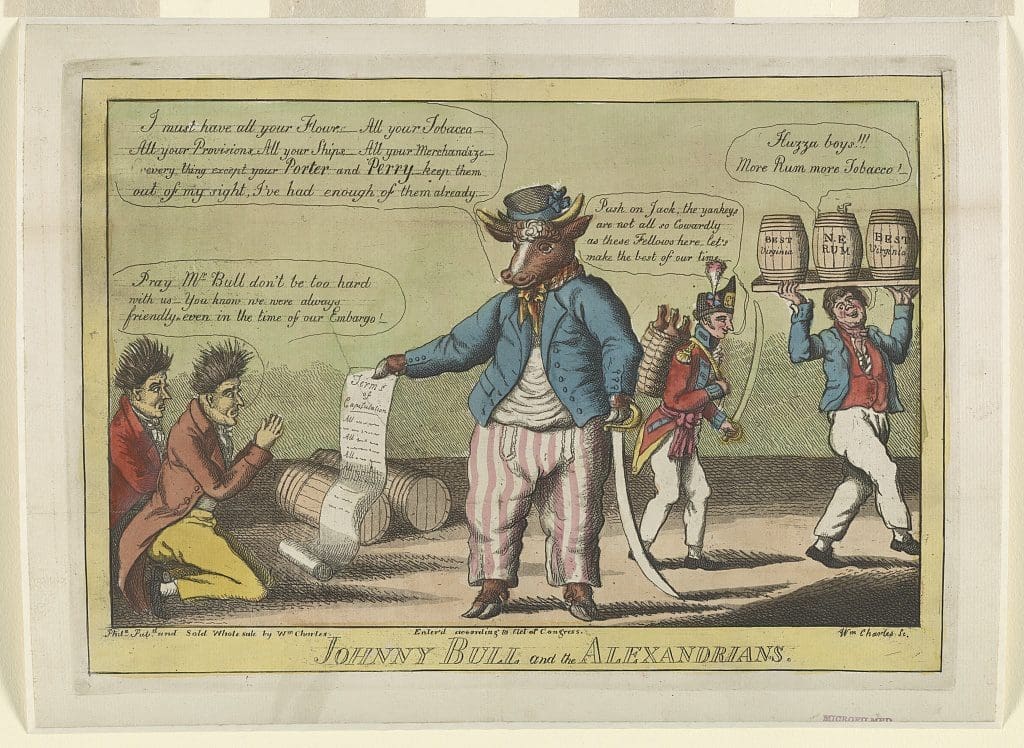

Upon meeting, Gordon set forth his terms: in exchange for sparing the town, he demanded all goods and supplies, encompassing commodities like flour and tobacco. Moreover, he insisted on surrendering all armaments and the 21 vessels anchored in the port. Faced with the explicit threat of bombardment and devoid of viable alternatives, Alexandria acquiesced to his demands.

Public Outcry

When news of this capitulation reached the broader nation, it was met with scorn. Newspapers lambasted the town’s decision, branding the residents of Alexandria as cowards.

The Tense Days at Alexandria

British Plundering Activities

Over the subsequent days, Gordon’s forces were hard at work. They commandeered captured merchant vessels and loaded them with a massive bounty, including 16,000 barrels of flour, 1,000 hogsheads of tobacco, 150 bales of cotton, and various commodities like wine, coffee, sugar, cigars, sails, and ropes.

U.S. Observers from Shuter’s Hill

From the vantage point of Shuter’s Hill, a towering elevation west of Alexandria, two U.S. Navy Captains, David Porter, Jr., and John Creighton, watched the British activities below. Today, the George Washington National Masonic Memorial marks this historic site.

Alongside Porter is Captain Creighton, the captain of the “USS Argus.” Both Creighton’s ship, the “USS Argus,” and Porter’s ship, the “USS Columbia,” were destroyed at the Navy Yard to prevent the British from capturing and commandeering them. River. IMAGE / © GERRY EMBLETON)

The British held a particular disdain for Porter due to his audacious operations aboard the USS Essex. Following the commencement of the war in June 1812, Porter embarked on a naval spree, seizing ten British vessels that summer. His most significant capture came in January 1813 with the British mail packet Nocton, which held a substantial cache of gold bullion. Porter’s venture into the South Pacific saw him capturing numerous British whalers and engaging in several battles. However, his streak ended on March 28, 1814, in a fierce battle against two British vessels. Suffering heavy casualties, Porter was compelled to surrender but later returned to New York, hailed as a hero.

Capture Attempt and Subsequent Tension

Amid their vigil, Porter and Creighton noticed a young British midshipman detached from his unit, apparently plundering from the town. The duo approached stealthily and seized the chance to capture a British officer and potentially gather intelligence. Their capture attempt became a struggle, with the midshipman resisting fiercely. The noise drew the attention of the British, who promptly readied their carronades and heavy naval cannons, leveling them threateningly at Alexandria.

Mediation by Mayor Simms

In this tense standoff, Mayor Simms intervened, urgently conveying to Gordon that the town had neither orchestrated nor endorsed the skirmish with the midshipman. He emphasized their lack of control over federal forces. Assuaged but still wary, Gordon called off the imminent assault, warning that further provocations would not be tolerated lightly.

After the conflict with the midshipman, Porter receives instructions from Secretary of the Navy William Jones to bring together a group of men at the Belvoir Neck. This piece of land juts into the Potomac River just below Mount Vernon. A tall cliff, about 40 feet high, looks over the river. Jones instructs Porter to attempt to destroy the enemy’s fleet as it travels down the Potomac. Close to a white house on the shore, Porter orders the Virginia and District of Columbia militia to construct trenches and gun platforms in preparation for the upcoming battle.

The Mysterious Absence of the Potomac Squadron

The Search Begins

In the waning days of August, the British sensed an anomaly with the whereabouts of the Potomac Squadron. To locate Gordon, they dispatched the HMS Fairy up the Potomac. On September 1, 1814 afternoon, an ambush awaited them. As the Fairy cruised past a white house on the riverbanks below Belvoir Neck, a barrage of gunfire and cannon blasts targeted the ship. The Fairy, caught in the onslaught, retaliated with a single salvo towards the bluff and sailed upstream. Dominating the ridge above the white house lay the brick remnants of Belvoir, the Fairfax family mansion, which had succumbed to flames in 1783. The Fairfax family lent their name to what is now known as Fairfax County, Virginia.

Reinforcements Arrive

As dusk enveloped the region, reinforcements streamed in, bolstered by two mighty eighteen-pound cannons. The firepower near the White House now boasted five formidable cannons. When news of the Fairy’s unexpected skirmish reached Gordon, he promptly rallied his ships and the 21 captured vessels laden with Alexandria’s riches to embark at dawn on September 2nd. Their mission: to navigate past the White House batteries. Fate, however, threw a curveball. As the ships commenced their journey, a swift change in wind direction slackened their sails.

Delayed Plans and Trapped Ships

General Robert Young and his 1st Regiment, DC Militia from Alexandria, finally arrived at Belvoir Neck later than expected. Their initial directive was to bolster Fort Warburton, but its premature destruction by Dyson derailed those plans. Young was a man of many accomplishments. He was a bank president, merchant, Consul to the Port of Havana under Jefferson, a Revolutionary War veteran, and cavalry commander at Washington’s funeral. His legacy also included the construction of 1315 Duke Street, which later became the base for the slavers Isaac Franklin and John Armfield in Alexandria.

Meanwhile, the Potomac Squadron grappled with the river’s whims. Capricious winds and treacherous riverbeds marred their voyage downstream. Ships frequently ran aground; though many were quickly dislodged, some remained ensnared for extended periods. A case in point: the HMS Devastation was mired in a mudflat for ten hours on September 3rd. Sensing an opportunity, the Americans dispatched flammable-laden vessels towards the trapped ship. However, quick-thinking British sailors in smaller crafts thwarted these fiery advances, redirecting the dangers. This cat-and-mouse tactic ensued for two more times over the grueling five-day confrontation.

The Rocket’s Red Glare

Closer to the heart of the confrontation, Gordon took the offensive near Belvoir Neck. Deploying a weapon of intimidation, he ordered his ship to launch its Congreve rockets against the American defenders. At first, the sight and sound of these rockets sowed fear among the local combatants. But with time and observation, they discerned a strategy: running toward the fiery projectiles reduced their impact and helped extinguish their flames. As night enveloped the battleground, these rockets painted the sky with bursts of illumination, reminiscent of the famed “rocket’s red glare.”

The Roar of Battle: A Bombardment Echoing to Georgetown

The Explosive Fourth Day

On the morning of September 4th, the British ships unleashed their deadly payload of bombs and rockets. As the battle escalated, American militia observed a boat north of Mount Vernon “warping” downriver and swiftly engaged it near what is today known as River Farm, currently the headquarters of the American Horticultural Society. Sensing the expanding battlefield, Gordon intensified his assault, directing even more munitions toward the White House batteries. The fierce exchange saw an estimated 700 mortar shells fired, utilizing 13-inch and 10-inch mortars, as well as rockets. Without any natural defense, the Americans bore the brunt of this onslaught. A particularly gruesome account detailed a young boy cut in two by cannon fire. The thundering sound of the bombardment carried so far that residents in Georgetown, D.C., could hear it.

The Strengthening American Resistance

American militia reinforcements continually streamed into Mason Neck. Captain McKnight’s unit, the Alexandria Independent Blues, joined the fray. McKnight, who once owned a tavern at the intersection of King and Royal Streets in Alexandria, had the distinction of leading the last regiment inspected by George Washington. (For those interested, a brochure featuring Captain McKnight can be found [here])

The British Counterattack

The British dispatched small boats intending to sabotage the American guns to silence the batteries. An intense close-quarter skirmish followed, which concluded with the British being repelled.

Unrelenting Battle

Despite the limitations of the American artillery, their lightweight cannons and small arms proved effective. They managed to breach the ship’s exteriors, damage their rigging, masts, and sails, and, more critically, wound or kill British personnel. The combat was unyielding, stretching from the break of dawn until midnight.

Nighttime Skirmishes on the Potomac

Under the veil of night, the Americans initiated a stealthy boat assault against the British. However, the British retaliated, prompting the Americans to divert to the river’s opposite bank. This diversion, concealed by darkness, went unnoticed by the British. As the British searched for the elusive American boats, Maryland troops lying in ambush on the riverbank opened fire. This resulted in significant casualties, including a lieutenant from the HMS Fairy. A tragic case of friendly fire ensued as the Potomac Squadron, mistaking the commotion for an enemy attack, fired upon their British boats. The night resonated with the anguished cries of the wounded. But by midnight, a haunting silence prevailed, marking the close of the battle’s fourth day.

The Ferocious Fifth Day: Battle on the Potomac

Preparation and Strategy

On the dawn of Monday, September 5, the Americans, replenished with fresh gunpowder and bullets, braced themselves for the day’s confrontation. By around 11:00 a.m., nature began to favor the beleaguered British squadron with a favorable wind, a boon they had been deprived of for days. Seizing this opportunity, Gordon devised a quick yet innovative tactic. Directing his captains to redistribute weight to the ships’ left side and dismantle the right-side railings, they transformed their vessels into improvised mortars.

A Frightening Barrage

Buoyed by the wind, the British squadron and their captured prize ships sailed past the American batteries. As they progressed, they unleashed a fierce onslaught upon the American positions. Captain Porter, in a subsequent report, provided a vivid account:

While the vessels were passing the fort, the firing was tremendous, the cannon shot, grape, canister, etc., fell like hail. The crashing in the woods, covered by the shoreline, was prodigious; large trees were often felled by the enemy’s 32’s, 24’s, etc. The falling limbs and splinters created chaos in all directions. We faced significant exposure during the intense cannonade but later found refuge behind a hill’s crest. Surprisingly, given the sheer volume of enemy fire, our casualties were minimal, with around 10-12 fatalities and 15-20 wounded. The majority of enemy shots missed their mark, with very few meeting their intended purpose. Observations showed visible damage to the enemy’s rigging.

O’Neill, P. L. (2014). “To annoy or destroy the enemy” The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington.

After engaging in intense combat for two hours, during which seven enemy combatants were confirmed killed and 35 wounded, the total casualties for American forces stationed at the White House Battery reached 12 fatalities and 17 wounded. Notably, among these casualties, two fatalities and two wounded soldiers were from Captain Janny’s unit. One of the soldiers killed was Robert Allison, the grandson of Alexandria’s founder, William Ramsay.

Tribute to the Fallen

The Alexandria Gazette, in its subsequent edition, eulogized a fallen hero:

Was killed in the recent clash at the White House, Mr. Robert Allison, who had showcased immense valor. The departed, aged 27, was the son of the late Sir Robert Allison. He had always epitomized the roles of a loving son, a magnanimous friend, and a valuable societal member.

O’Neill, P. L. (2014). “To annoy or destroy the enemy” The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington. p. 191.

The Final Stretch and Battle’s End

After navigating past Belvoir Neck, the British squadron faced another arduous six-hour journey, confronting the American defenses on the Maryland coast at Indian Head. The British fleet, using all its weaponry, faced intense resistance, resulting in two of its ships incurring significant damage. Yet, none succumbed to the American might.

By the dawn of September 6th, the beleaguered British fleet and their captured vessels finally found their escape route, marking the culmination of the intense five-day conflict at the White House Landing.

Reunion at the Kettle Bottoms

On September 8th, as the squadron approached the Kettle Bottoms, distant sails appeared on the horizon, just beyond the shallows downriver. These were the advanced ships of the main British fleet rushing upstream to rescue Gordon’s beleaguered squadron. Twenty-three days after their initial deployment, the Potomac Squadron’s mission was deemed complete, leading to its disbandment.

A Shift in Strategy

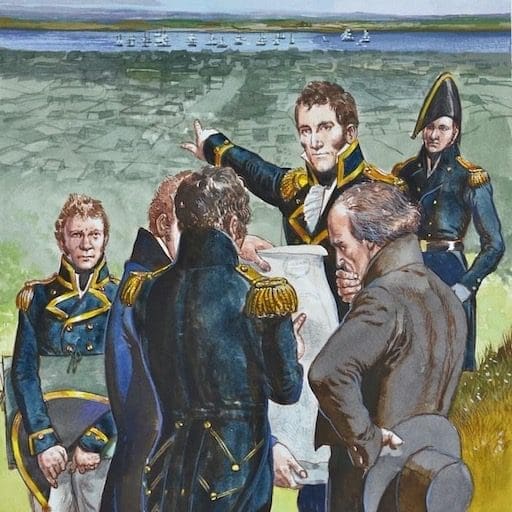

Upon meeting with Gordon, Admiral Cochrane, aboard the H.M.S. Tonnant, reviews the recent battle report. The skirmish claimed the lives of approximately seven British sailors, with 35 more injured. Notably, three of Gordon’s subordinate captains were among the casualties.

Learning that his nemesis, Captain David Porter, had led the defensive efforts at the White House batteries, Cochrane’s anger knew no bounds. Driven by this newfound animosity and the urge to retaliate, he reconsidered his initial military strategies. Instead of waiting until November to mount an attack on Baltimore, Cochrane advanced the timeline to the present month. In preparation, he dispatched swift vessels to recall the ships he had previously sent to Rhode Island and Bermuda. Their immediate return was crucial for the upcoming assault on Baltimore.

Siege of Fort McHenry

From September 13 to 14, 1814, Fort McHenry faced a relentless onslaught from Cochrane’s fleet. For a grueling twenty-five hours, the British unleashed a barrage of over 1500 cannonballs, mortars, and rockets. Interestingly, some of these formidable vessels had previously engaged the White House defenses earlier that month.

However, by the morning of September 14, the British acknowledged their inability to conquer the fort and redirected their course towards New Orleans, Louisiana. It was there, on January 8, 1815, that they faced a crushing defeat with significant casualties. Unbeknownst to the battling forces, the War of 1812 had already found its formal end with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

The Tale of Dr. William Beanes, Francis Scott Key, and “The Star-Spangled Banner”

Mission to Free Dr. Beanes

General John Mason, leader of the District of Columbia Militia (now recognized as The District of Columbia National Guard) and Commissioner General of prisoners during the War of 1812, entrusted Georgetown lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key with a mission: to liberate Dr. William Beanes from the British prison ship, the Tonnant. In the company of fellow lawyer John S. Skinner, U.S. Agent for Prisoners of War, Key approached the Tonnant near the Potomac River, coinciding with Admiral Cochrane’s strategizing for the impending assault on Baltimore.

While trying to free Dr. Beanes, the duo inadvertently became privy to the British battle plans. Despite securing Beanes’ release, the trio was relocated to an American ship tethered to a British warship, which provided them with a front-row seat to the Battle of Baltimore at Fort McHenry.

The Birth of a National Anthem

On the morning of September 14th, a deeply moved Key, gazing through a spyglass, spotted a prominent 15-star American flag billowing over the fort. Emotionally stirred, he began drafting lyrics for a well-known British tune, “The Anacreontic Song,” the anthem of the Anacreontic Society of London. The tune, composed by John Stafford Smith, had previously been adapted by Key in 1805 for a tribute to naval hero Stephen Decatur.

By September 16th, after being released from the truce ship, Key refined his lyrics at the Indian Queen Hotel in Baltimore. This work, originally titled “Defense of Fort M’Henry,” gained rapid popularity. Within weeks, its name transformed into “The Star-Spangled Banner.” By 1931, the United States’ national anthem was christened, succeeding the interim anthem “Hail Columbia.”

Legacy and Later Years

Throughout his life, Key penned lyrics for other renowned melodies. In 1832, he crafted “Before You, Lord, We Bow” to a tune by English composer John Darwall. This hymn remains a staple in American churches. Key was also pivotal in forming the American Colonization Society in 1816, alongside other luminaries like Henry Clay, Bushrod Washington, and Phillip Richard Fendall II.

The latter, Phillip Richard Fendall II, married Elizabeth Mary Young in 1827. During the Battle of the White House, her father was General Robert Young, Allison’s commanding officer. They, along with Allison, are interred in the Presbyterian Cemetery. Key’s life journey concluded on January 11, 1843, with his burial in Mount Olivet Cemetery, Frederick, Maryland.

Dr. Beanes’ Final Days

After the tumultuous events, Dr. Beanes retreated to Upper Marlboro, Maryland, where he lived out his days, passing on October 12th, 1828, at 79.

Proximity in Rest: General John Mason and Robert Allison, Jr.

General John Mason, who dispatched Key on his pivotal mission to rescue Dr. Beanes, rests in Christ Church Episcopal Cemetery in the Wilkes Street Cemetery Complex in Alexandria, Virginia. Intriguingly, Mason’s final resting place is but a stone’s throw away from the grave of Robert Allison, Jr., drawing yet another connection between these pivotal figures of history.

Gordon’s distinguished deeds on the Potomac River elevated him to the stature of a hero. With time, he climbed the ranks, ultimately holding the esteemed title of Admiral of the Fleet. As time passed, he was recognized as the last surviving captain among Nelson’s trusted commanders, drawing his final breath on January 8, 1869.

Such valor was not forgotten in the annals of literature and entertainment. C. S. Forester considered Gordon’s illustrious career the foundation for his protagonist in the Horatio Hornblower book series. Building on this legacy, television maestro Gene Roddenberry drew inspiration from Hornblower in crafting the Star Trek universe and creating the iconic character Captain James T. Kirk.

Preserving History: Sites of the White House Landing Battle

The Transformed Battlefield

Once echoing with the sounds of battle, the terrain of the White House Landing and the very White House for which it was named have since vanished from sight. By the early 1900s, these historic sites had been completely razed. Today, the area known as the Belvoir Neck is encompassed within the U.S. Army military base, Fort Belvoir. While gaining entry to this specific zone might be challenging, the modern-day Fort Belvoir Officer’s Club is a sentinel on the hill. This site, once the vantage point of artillery units, now offers visitors a stunning panoramic view of the Potomac River.

Remembering a Hero: Robert Allison, Jr

Honoring Private Robert Allison, Jr.

Following the turmoil of battle, on September 6, 1814, the military accorded Private Robert Allison, Jr. with due honors as he was laid to rest in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia. The Reverend James Muir led the ceremony, then the Pastor of the Presbyterian Meeting House.

Decades later, on April 21, 1929, the National Society United States Daughters of 1812 dedicated a special plaque to immortalize Allison’s contributions. This commemorative plaque is on the eastern wall of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House.

Two Centuries On A Solemn Tribute

Two hundred years after Robert Allison, Jr.’s ultimate sacrifice, his memory was honored with a special ceremony organized by the War of 1812 Society at his resting place. Year after year, as the anniversary of his passing approaches, floral tributes adorn his grave. These tender gestures serve as a homage not just to Allison but also to the valorous American soldiers who stood their ground during the Battle of the White House Landing from September 1 to 5, 1814.

The Legacy of the Battle

Today, Allison’s gravestone stands solitary in its testimony of that crucial historical juncture. It remains a poignant reminder of the “Battle at the White House (Landing),” a skirmish that inadvertently altered the British’s tactical timeline, pushing them towards an accelerated assault on Fort McHenry in Baltimore.

This chain of events culminated in an iconic morning on September 14, 1814. Aboard a truce ship, Francis Scott Key beheld the dawn’s early light over Fort McHenry. The sight of the American flag, unfaltering amidst the smoke of battle, moved him profoundly. This moment of inspiration and hope birthed the poetic verses that would eventually be adopted as the beloved national anthem of the United States.

Author’s Note:

My introduction to this captivating tale dates back to 1975, when the renowned Alexandrian Historian and Poet Jean Elliot first shared it with me. Jean and her husband held membership at the Old Presbyterian Meeting House, where I was raised. The Battle of the White House narrative has since become my cherished anecdote, often recounted during my guided walking tours of the Wilkes Street Complex. As I recount the story, echoes of Jean’s voice still resonate in my mind, effortlessly relaying the same account. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to Jean for recognizing my fervor for history. Much of my indebtedness is owed to her.

For those seeking to learn more about Jean Elliot, I invite you to explore her legacy on this blog: [Remembering Jean Robertson Elliot (1901-1999): a Poetic Journey Through Alexandria, Virginia].

Sources of Information

Todd, F. P. (1948). The militia and volunteers of the District of Columbia 1783-1820. Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., 50.

Lord, W. (1972). The dawn’s early light. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Daughan, G. C. (2013). 1812: The Navy’s war. Basic Books.

Vogel, S. (2013). Through the perilous fight. Random House, LLC.

Vance, R. L. (Ed.). (2014). Home of the brave. American History, 49(4).

O’Neill, P. L. (2014). “To annoy or destroy the enemy” The Battle of the White House after the burning of Washington.

Dahmann, D. C. (2022). The roster of historic congregational members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. Alexandria, VA: Old Presbyterian Meeting House. Unpublished.

National Park Service. (2022). James Alexander Gordon. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

U.S. Army. (2022). Belvoir Neck’s history. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

National Park Service. (2022). Fort Warburton’s history. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

Military History. (2022). Raid on Alexandria. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

HistoryNet. (2022). David Porter. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

National Park Service. (2022). Fall of Fort Washington and the Battle of the White House Landing. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

National Weather Service. (2022). August 25, 1814 Tornado in Washington. Retrieved August 2022, from [website]

Colonial Music Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved from George Washington’s Mount Vernon [website].