If you haven’t read the first installment of this series, see Part 1 [here].

Paving the Way: The Washington and Alexandria Turnpike

In 1808, Alexandria set its sights on a groundbreaking endeavor: the inception of the Washington and Alexandria Turnpike Company. This ambitious initiative sought to bridge Alexandria and Washington, heralding a new era in transportation. Modern Route 1 traces the path of the Alexandria and Washington Turnpike.

The Alexandria Canal

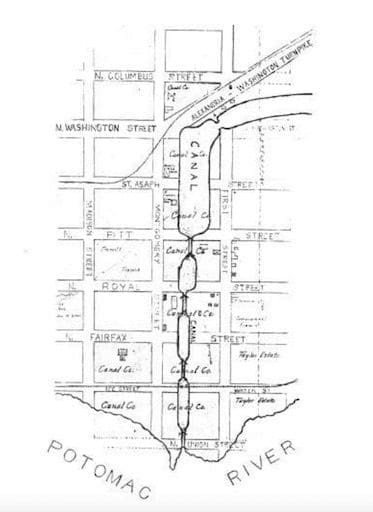

The 19th century witnessed the fervor of “canal mania.” The Erie Canal, initiated in 1817, was at the forefront of this excitement. In 1828, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company envisioned a canal connecting Washington, D.C., to the upper Potomac. In the same spirit, the Alexandrians constructed the Alexandria Canal.

In late 1843, the Alexandria Canal, a seven-mile extension of the 185-mile C&O Canal, was unveiled. This canal linked the Potomac River to the C&O Canal, which stretched from Cumberland, Maryland, to Georgetown, D.C. The Alexandria Canal operated from 1843 until 1886, and traces of its original path can still be observed along the George Washington Parkway, located north of Alexandria, particularly between Bashford Lane and Second Street north of Old Town.

While the Alexandria Canal threatened Fendall Farm, its prominence was short-lived due to the emerging dominance of railroads.

Railroads: Charting New Territories

The dawn of the 1830s witnessed Virginia’s maiden venture into the realm of railroads. Initially conceived for regional commutes, these rail networks swiftly transformed into transportation lifelines, bridging remote areas to river ports. By the 1880s, the railroad phenomenon had reshaped American mobility, positioning Alexandria as a crucial southern nexus on the national railway grid.

Potomac Yards: The Railroad Crown Jewel

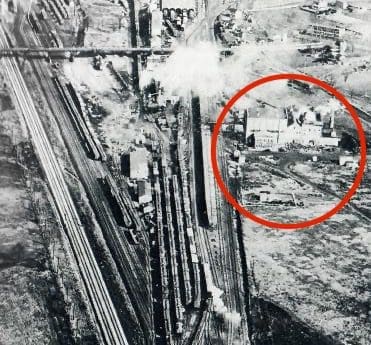

The turn of the 20th century, specifically 1902, saw the emergence of the Potomac Yards. This colossal railyard became a melting pot for trains from six distinct railroad corporations, establishing itself as a pivotal juncture for merchandise and travelers.

The Displacement of Alexandria’s Historical Legacy

Amidst Alexandria’s rapid development, its cherished historical sites were often at risk. The emergence of Potomac Yards led to the removal of the Preston Plantation. However, the Fendall private cemetery, a symbol of endurance, remained intact for years within the Mutual Ice Company’s (MICO) premises. But as Potomac Yards continued its ambitious growth, this haven was in looming danger.

In 1913, MICO set up its Potomac Yards facility to provide ice to the railway. MICO specialized in cooling railroad cars for over fifty years, primarily using ice from deep water wells 200 and 500 feet below ground. They provided vast amounts of ice for the Fruit Growers Express and other railcars transporting perishables. By 1971, technological advancements in mechanical refrigeration rendered ice-cooled railcars redundant, leading to their eventual retirement. In 1989, MICO sold its Potomac Yard location, which was later redeveloped into the Braddock Gateway residential towers. The family-run business officially ceased operations in 2012.

Braddock Gateway’s Archaeological Insights

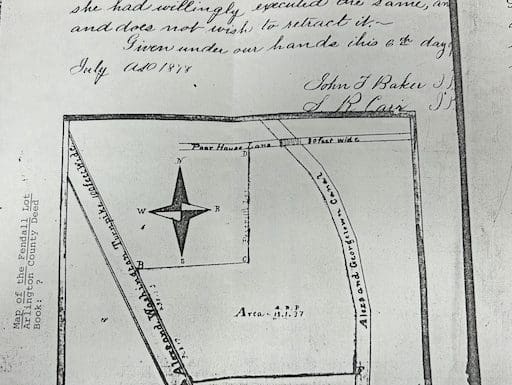

In 2013, an archaeological evaluation occurred at the former Fendall Farm site before the Braddock Gateway property’s construction in Alexandria, VA. This site, now home to four primarily residential buildings, was once the Fendall Farm’s location. The evaluation’s goal was to determine the potential location of the historic Fendall family cemetery. While artifacts from the late 18th or early 19th century were discovered, suggesting a historical dwelling once existed nearby, no grave shafts were found. While concrete evidence is lacking, those buried in the Fendall Family Cemetery were probably disinterred and reburied elsewhere in the mid-20th century, specifically during the 1940s or 1950s, possibly due to a MICO expansion.

The Fendalls’ Relocation: A Testament to Preservation

As recorded on the Family Heritage website, Philip Richard Fendall and his family were relocated to Ivy Hill Cemetery, reflecting Alexandria’s commitment to preserving its historical legacy. However, as years passed, the details of this relocation faded from memory. As a result, historians erroneously believed that the Fendall family had been lost during MICO’s expansion of Potomac Yards. This oversight underscores the challenges of upholding historical records amidst continuous urban development.

Tracing the Fendall Lineage: A Dive into Ivy Hill’s Records

Building on this historical narrative, in his relentlessly pursued clarity, Heiby contacted Lucy Goddin, the President of the Ivy Hill Historical Society, and Catherine Weinraub, the Society’s dedicated Historian. Immersing themselves in past records, Weinraub discovered a card confirming the internment of P. R. Fendall in Section B, Lot #1. Adding to the intrigue, this card highlighted the conspicuous absence of markers for the burials within this particular lot.

Ivy Hill Cemetery: A Historical Haven

Founded in 1856, Ivy Hill Cemetery, nestled in Alexandria’s Rosemont District, became the eternal abode for nearly 10,000 individuals. Its residents included Congressional members, heirs of the Washington and Fairfax lineages, and other luminaries. Within these hallowed grounds, the enigma of Philip Richard Fendall’s final resting place intensifies.

The Archaeological Pursuit

Renowned archaeologist Mark Ludlow, celebrated for his extensive research in Alexandria, was enlisted to authenticate the historical records of the cemetery. Employing ground-penetrating radar, Ludlow methodically scrutinized the purported Fendall burial site. His discoveries indicated the likelihood of a casket potentially associated with Philip Richard Fendall. Subsequent inquiries hinted at the gravesites of Fendall’s two spouses, along with additional possibilities yet to be confirmed.

The Final Thought

While the mystery persists, the evidence presented indicates that the unmarked grave in Section B, Plot 1 of Ivy Hill Cemetery, might indeed be the final resting place of Philip Richard Fendall I. This exploration underscores the delicate interplay between advancement and the preservation of history. Armed with the available information and contemporary technological tools, readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions and ponder the narratives that have molded our history.

Sources of Information

Baicy, D. (2019, December). Braddock Gateway: Archeological investigation and evaluation (WSSI #21677.03). Thunderbird Archeology. https://media.alexandriava.gov/content/oha/ArchaeologySiteReport1200NFayette44AX223.pdf

Bromberg, F. W. (n.d.). The history of Potomac Yard: A transportation corridor through time. Alexandria Archaeology.

Dahmann, D. C. (2022). The roster of historic congregational members of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House. Old Presbyterian Meeting House Archivist.

Files and clippings about the Fendall family. Alexandria Library, Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library, Local History and Special Collections Division, Alexandria, VA.

Griffin, W. E., Jr. (1984). One hundred fifty years of history: Along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. Whittet & Shepperson.

Hahn, T. S., & Kemp, E. L. (1992). The Alexandria Canal: Its history & preservation (Vol. 1, No. 1). Institute for the History of Technology & Industrial Archaeology, West Virginia University Press.

Hopkins map of Alexandria County, Virginia: Includes the present Arlington County and the City of Alexandria, circa 1878.

Hurst, H. W. (1991). Alexandria on the Potomac: The portrait of an antebellum community. University Press.

Lee, C. G., Jr. (1957). Lee Chronicle: Studies of the early generations of the Lees of Virginia. Thomson-Shore. (Published for The Society of the Lees of Virginia)

Morgan, M. G. (n.d.). A chronological history of Alexandria Canal (Part II). Arlington Historical Society. (Accessed May 2023).

Mullen, J. P. (2023, June). Braddock Gateway – Phase II: Cemetery investigation. Thunderbird Archeology. https://media.alexandriava.gov/content/oha/ArchaeologyCemeteryInv1200NFayette44AX223.pdf

Roberts, J. (2015). Jaybird’s jottings: Rails in the seaport—A brief look at the history of railroads and their tracks in Alexandria.

The Archives of the Ivy Hill Cemetery were graciously opened to me by their Historian and Archivist, Catherine Weinraub—also, special thanks to Lucy Goddin, President of the Ivy Hill Cemetery Historical Society.

Thunderbird Archeology. (2007). Documentary study for the Potomac Yard property, Landbays #, G, H, I, J, K, L, and M, City of Alexandria, Virginia. Gainesville, VA.

Workers of the Writer’s Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Virginia. (1940). Virginia: A guide to the Old Dominion. Oxford University Press.